What is Glyndebourne? A middle-aged Bullingdon. That’s a common view: a luxury bun fight for past-it toffs who glug champagne, wolf down salmon rolls and pass out decorously on the lawn. But the reality is that it caters to those of my class (lower-middle) who want to boost their pedigree with an eye-catching essay in sophistication. The Sussex opera house was founded in 1934 by John Christie, a passionate and eccentric millionaire who believed the public should suffer for his art. He hated the idea of suburban businessmen ‘catching a show’ for two hours in the West End before falling asleep on the train home. He wanted his audiences to devote an entire day to his productions. His first theatre, a 300-seat tiddler, was too small for his adored Wagner and he was persuaded by his German producers that Mozart would be a better match for the cramped venue. Christie considered the Salzburg ditty-meister a superficial talent but he accepted their advice and his opening season featured The Marriage of Figaro and Così fan tutte.

Roger Allam is almost unrecognisable as the bald Christie with his thick grey thatch concealed by a wrinkled white scalp like the skin of a rice pudding. Allam’s warm, rasping voice can move imperceptibly between exasperation and humour and he gives a brilliant account of Christie as a bluff, art-loving oddball at war with philistinism. Nancy Carroll plays his wife, the ‘moderate soprano’ (i.e. ‘useless but tries hard’), who relied on Christie to ensure her inclusion in the Glyndebourne company. She’s a typical pre-war simperer in a scarlet frock who dances attendance on her husband like a puppy in need of a biscuit. That’s a shame. Carroll is a class act and she deserves better from a script that sometimes leaves her on stage for five minutes with nothing to do but stand there twinkling mutely.

The Moderate Soprano’s structure is a little guileless as it flits between the 1960s and the 1930s. A narrator trots in and out to tell us where we are. This sat-nav device excuses David Hare the labour and discipline of making the story spring organically from the interactions of the characters. And he touches obliquely on the great debate about nationalised art. Those who resent the prejudices of the Arts Council will realise from this play that the alternative, i.e. private sponsorship, generates an identical problem and leaves creative people at the mercy of wilful amateurs who want to bully, fume and interfere at every point. This is an efficient, witty documentary that plumbs no great depths and stirs no volcanoes into life. It probably hasn’t the oomph to sustain a West End run. Ideal destination: Glyndebourne itself.

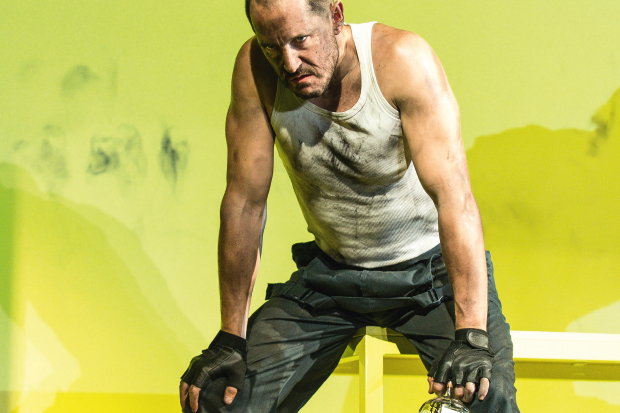

New broom Matthew Warchus has abandoned Kevin Spacey’s star-led populism at the Old Vic. His latest offering, The Hairy Ape, is an obscure experiment from the 1920s performed by a company without an international celeb. And the Vic is a huge theatre to fill. Impresarios go bankrupt this way. On paper, Eugene O’Neill’s play seems to stick two fingers up to the public. It’s a surreal fantasy, almost a monologue with illustrations, about an embittered, thuggish sailor named Yank who goes in search of his proletarian self in the big bad city. The odyssey is triggered by a spoilt millionaire’s daughter who sneaks into the stokehold on her father’s ship. When she spots the grime-encrusted Yank shovelling coal into the engine’s crimson throat, she cries out ‘filthy beast’ and faints into the arms of a blushing seaman. Confused and angry, Yank prowls the New York ghetto in search of answers. All he finds is captivity in various forms. He turns to theft and winds up in the slammer. He’s tempted by the friendship of radical Marxists who then arrest him as a police spy. His final gesture is to break into the ape-house at New York zoo and swap places with a silverback gorilla.

Director Richard Jones lays on a full roster of expressionist techniques, co-ordinated laughter, synchronised table-banging, freeze-frame moments, and citizens in head-masks dancing across the stage in orchestrated diagonals. Some viewers couldn’t stomach these zany contrivances and headed for the exit. Most stayed. It was well worth it just to see a fresh side of O’Neill, whose best-known plays are rich, sprawling melodramas that go on far too long. This is a stark, narrow glimpse of a young man’s descent into hell that zips past in 90 minutes. The writing is terse, pacy and relentlessly brutal. Designer Stewart Laing has created a series of tableaux that match the script’s muscular ugliness beat for beat. And the play is a fascinating social document that portrays America as a culture stratified by class with the layers separated according to degrees of inherited wealth. Just like here. Exhilarating stuff. But not to everyone’s taste.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in