Time was when early music was a 6 p.m. concert, Baroque began with Bach and ended with Corelli’s Christmas Concerto, and speeds were so portentously slow that you’d have to start the B Minor Mass shortly after lunch in order to make it home in time for bed.

Those dark days — caught between Baroque and a hard place — are over now. Period ensembles have never been better or more numerous, Handel and Monteverdi are a staple of operatic programming, and even Vivaldi, Cavalli, Cesti and Steffani are making their mark. Baroque is back, and this time it’s here to stay.

One of the biggest success stories of recent years is the Globe’s new indoor theatre. Opened just last year, it’s already hard to remember musical life before the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. Seating just 340, its meticulously recreated 17th-century interior is the perfect frame for period operas intended to place their performers in knee-groping, beard-stroking proximity to their audience. Crucially, it’s the space that has finally solved the problem of early opera for the Royal Opera, allowing the company to tackle a whole new repertoire with a success its own unwieldy house would never allow.

You couldn’t imagine a greater contrast than that between the Royal Opera’s in-house 2008 La Calisto (distant, scratchy, ill at ease) and the giddy, romping delight of its debut Wanamaker production, a staging of Cavalli’s L’Ormindo. If the follow-up show — Rossi’s Orpheus — lacks the musical quality of Cavalli, it makes up for it in the determined charm and inexhaustible energy of its performance. Keith Warner’s production (with a little help from Christopher Cowell’s knowing English translation) swaps Italy for Caroline England in a tragicomedy whose deliberate anachronisms chafe with a friction as delicious as Euridice’s comic death scene. With most of the cast under 35, it was a chance to hear the next generation of voices. Between Louise Alder, Siobhan Stagg, Keri Fuge and Lauren Fagan it’s a future with no shortage of superb sopranos.

While Handel and Monteverdi are now core repertoire, it wasn’t so long ago that they were curiosities, receiving tentative contemporary premières. Conductors and musicologists now have to dig a little deeper into the archives to find unfamiliar works, and while we can’t expect a Poppea or a Rodelinda every time, the quality is still strikingly high.

Take L’Ospedale, for example — an anonymous 17th-century opera premièred recently at Wilton’s Music Hall by the Baroque collective Solomon’s Knot. A scalpel-sharp satire on the medical profession brought uncomfortably up to date in director James Hurley’s slick production, it’s a work whose contemporary resonances alone would merit it a place in the repertoire, even if these were not set to expressive, Cavalli-esque melodies and muscular instrumental dances.

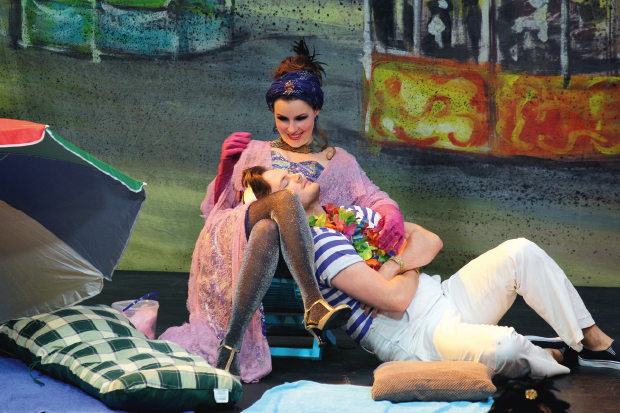

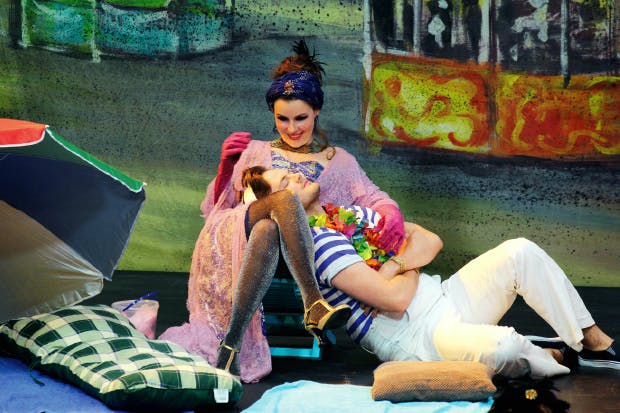

Even stronger, perhaps, is the case for Francesca Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero, championed recently by the Brighton Early Music Festival in a new production by Susannah Waters. This full-length comic take on sorcery and seduction has its tongue firmly in its cheek. Graceful duets and trios, sustained arioso and richly coloured orchestral writing gild a piece of period silliness that slips down every bit as easily now as it did four centuries ago.

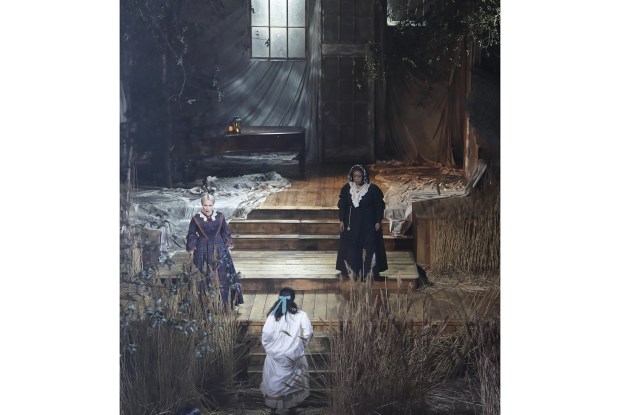

Part of Baroque opera’s pervasive appeal is surely that, as art forms go, it’s actually not very baroque. Instead of endless fiddly curlicues and fussing ornaments we get smooth, long vocal lines, crisp, clean rhythms — at least, in those composers now revived (pace Vinci). If it weren’t for all the kings and shepherdesses it would all feel thoroughly modern, something directors have long capitalised on in their productions. Harry Fehr’s recent Orlando for Welsh National Opera picks up where David Alden and David McVicar left off at ENO, recasting Handel’s sorcery story as one of psychological trauma and war. Orlando himself becomes a patient in a second world war sanatorium, blasted with bouts of electricity by ‘doctor’ Zoroastro to cure his PTSD. With a score cut aggressively (but not insensitively) back, Yannis Thavoris’s clean designs and an outstanding cast led by Robin Blaze, Fflur Wyn and Lawrence Zazzo, this is Handel with a modern audience in mind: emotional, direct, confronting. Where ENO has recently stumbled (Michael Keegan-Dolan’s senseless Julius Caesar, Richard Jones’s unexcitingly functional Rodelinda), WNO has stepped up. Hopefully, this marks the beginning of a new Handel sequence.

Glyndebourne is, of course, Handel’s greatest home in England, crowned by glorious productions of Giulio Cesare, Rodelinda, Rinaldo and, most recently, Saul. But where the company has fostered Handel (and, to some extent, also Purcell), it has refused to adopt the French repertoire still so neglected in the UK. A lone venture in that direction (2013’s Hippolyte et Aricie) is never, according to conductor William Christie, to be followed up. French Baroque simply doesn’t sell like its foreign contemporaries, making it too great a risk for the big houses.

Which leaves smaller outfits like Christian Curnyn’s Early Opera Company to step into the breach. Find anything exciting happening in period opera in the UK and Curnyn will be involved, whether it’s conducting at the Wanamaker or ENO, recording Handel or directing his own projects. Last week’s concert performance of Rameau’s Castor et Pollux was a perfect example. This is a work that simply shouldn’t work in concert, so reliant is it on spectacle and physicality to drive the drama. Yet such was the rhetorical clarity of Curnyn’s players, the dramatic skill of his young singers, that you felt no lack. With such vivid, compelling persuasion, surely the UK can’t continue to hold out against the charms of Rameau, Lully and Charpentier?

What a difference a decade (or two) makes. Baroque has gone from rags to riches, and it’s the UK that has led the way, whether in musicologists such as Edward J. Dent and Winton Dean, prescient directors like David Alden and Nicholas Hytner, or musical directors like Curnyn, Bicket, Hogwood and Gardiner. It’s thanks to them that opera’s history is also its future. There may be less brocade and fewer feathered headpieces this time round, but the music is just as good and the drama is even better.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in