Chords as bright and sweet as pomegranate seeds burst and spill in Turandot, a splinter of bitterness at their centre. Left incomplete at Puccini’s death in 1924, the opera is his most radical and most cruel. You can taste something of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in the instrumentation, a musky roughness that rubs against the Italian composer’s customary silky precision. Woodwind and strings cling to the voices of the monstrous princess Turandot, her intoxicated suitor Calaf, and Liù, the slave who slavishly adores him because he once smiled at her. So closely scored is the writing that it is almost suffocating. This is love as an addiction: violent, sleepless, lethal.

The renaissance of opera in Northern Ireland has not been timid or gentle. Under Oliver Mears’s direction, NI Opera has staged Tosca in three historically charged locations in Derry-Londonderry, and brought nudity to the stage of Belfast’s Grand Opera House in Salome. With this co-production of Turandot with Nuremberg and Toulouse, directed by Calixto Bieito and revived by Lutz Schwarz, NI Opera makes plain its ambitions to be an international force. No concessions are made for an audience starved of traditional stagings of Franco Alfano’s dewy completion or those who are squeamish about bodily fluids. Bieito’s Turandot runs without an interval and ends at the last bar to be completed by Puccini, with a hopeless lament for a pointless death.

The walls of Beijing are made of cardboard boxes, the city a factory producing plastic baby dolls for western export (designs by Rebecca Ringst). The workers wear identical blue overalls, their individuality blotted out. Only Olaf Lundt and Karl Wiederman’s lighting distinguishes the love-blind Calaf (Neal Cooper) and Liù (Anna Patalong) from the dust-masked masses around them. To Puccini’s vicious pentatonic parodies and fascistic choruses Bieito adds more images of repression: a burning bicycle, backs flowering with bruises. Ping, Pang and Pong (the finely blended Paul Carey Jones, Andrew Rees and Eamonn Mulhall) are army officers who cross-dress in their downtime, wearing bridal dresses and the hooker boots of the women they menace and torture. The women are silent, their mouths taped shut, their bodies wrapped in clingfilm, their knickers caked in dried blood. Terror is everywhere, except in the hearts of those mad with unrequited love, senile (Christopher Gillett’s pitiful, distracted, nappy-wearing Emperor), or with nothing to lose (Stephen Richardson’s anguished Timur). Projected on the walls behind them, a face is slowly painted over with Chinese figures until all that remains are its terrified eyes.

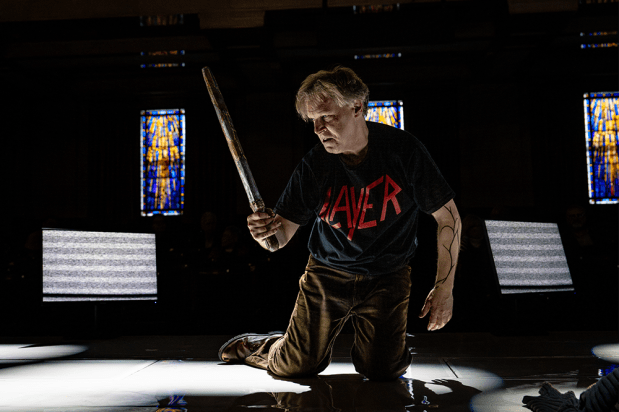

In this horror factory Turandot (Miriam Murphy) stalks her prey with icy, miserable fury. Bald as a baby beneath her garish blonde wig, frumpily dressed in the pants suit of a female premier, she is ugly within and without. Bieito has merely exaggerated the qualities already present in the music but it strands Murphy, whose pitiless characterisation leaves her weak at the bottom of her range. Undone by Calaf’s solving of the riddles, she weeps without feeling, smashing the skulls of the dolls, tearing their limbs from them. While Cooper is steadfast in his projection of Calaf’s crazy passion, delivering a sturdy ‘None shall sleep’ (‘Nessun dorma’), it is hard to feel pity for him. Only Anna Patalong’s ardent, gleaming Liù is presented as a sympathetic figure. For the rest, one can feel only awe at the brightness and vigour of NI Opera’s young chorus, and revulsion at the relentless crushing beauty of the orchestral writing. Turandot was a dystopic stretch for the Ulster Orchestra and conductor David Brophy, and perhaps for the audience too.

Janet Suzman’s Royal Academy Opera production of Le nozze di Figaro relocated Beaumarchais’s ‘Folle Journée’ to an artfully crumbling villa in pre-revolutionary Cuba, complete with smoking room. The power structure on which Mozart’s opera depends was already under siege in the overture. By the interval the merengue danced by the workers had dissolved into open hostility against Henry Neill’s Count Almaviva. The blocking was sometimes crude, the stage business sexy and perceptive, as Suzman pointed to the next episode in Beaumarchais’s trilogy and the affair between the sad Countess (Emily Garland) and an enchanted Cherubino (Katherine Aitken).

A Figaro sung by young voices affords unusual clarity in the ensembles. Conductor Jane Glover handled these with breezy expertise, drawing some divine details from the student orchestra. If Neill’s portrait of a handsome man too used to getting his own way and too quick to violence was strong, so too was Bozidar Smiljanic’s performance as his burly nemesis, Figaro. Charlotte Schoeters was a confident Susanna, low on deference, high on sass; Claire Barnett-Jones a touching Marcellina; Lorena Paz Nieto a scene-stealing, brilliantly characterised Barbarina even in her unscripted, silent appearances.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in