The other evening, surrounded by Christmas shoppers in the West End of London, I happened to glance up at the illuminations and was moved all over again by the old, old story. Yes, the sign was lit up once more over the defunct Raymond Revuebar, all that’s left of the club where men and women used to act out the ageless tragicomedy of desire.

Strange — even blasphemous — as it may seem, the lurid blazon of a topless dancer in feathers and stilettos affected me like a holly-decked hall or a Slade-loud department store. ‘Personal appearances of the world’s greatest names in striptease’, spelled out in throbbing neon, made me come over all festive, Christmassy even.

I’m a sucker for the season with all the trimmings, and I’d be the first to complain if I heard a vicar on Thought for the Day co-opting porny old Soho into the greatest story ever told. What can I say — who’d have thought you could have a sudden rush of peace and goodwill beneath Paul Raymond’s guttering go-go girl?

It’s good to have her back again. It’s more than a decade since the doors finally closed on Raymond’s grotty cockpit of the flesh, at the north end of Rupert Street, W1. The joint had a makeover to suit Soho’s new USP as London’s gay village. Out went the storied Naugahyde banquettes and the token disc of disinfectant in the stalls. I realised hotly what the old gaff reminded me of. It was those cards in telephone boxes. The Revuebar was pre-op.

It has since been transformed into a more sophisticated, metrosexual hangout. But the sign, inexplicably and delightfully, was retained. As various nightspots and dives went dark a garter’s throw from the old stage, Fawn James, Raymond’s granddaughter and heiress to his West End property empire, took the decision to turn the signage back on.

It’s a work of art in its own right, designed by a former miner, Dick Bracey, who left the pits for the bright lights of London, and ended up making many of them. It was restored by his son, Chris. Dubbed the King of Neon, Chris Bracey, from his studio God’s Own Junkyard, has designed bespoke lighting for films including Blade Runner, Eyes Wide Shut and Casino Royale. Bracey died a year ago at the age of 59 and is celebrated in a new exhibition at the Lights of Soho gallery.

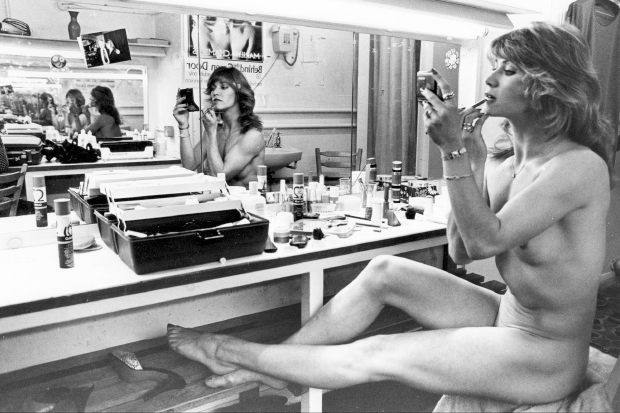

For all its godlessness, the Revuebar seems rather innocent now, a place where girls called things like Joy and Babs starred in spangled musical routines. It straddled a Larkin-esque faultline between Victorian attitudes to sex and the permissive society. Before the Revuebar, the Lord Chamberlain used to invigilate the nudie shows at the Windmill around the corner. Raymond gave him the slip by the masterstroke of making his venue members only, and so beyond his jurisdiction. The free love generation gave the club their blessing when the Beatles shot scenes for their film Magical Mystery Tour on the premises.

The Revuebar is a jewel in London’s crown, or rather a paste nipple-tassel in her wrinkled bodystocking, one of those gamy bits of heritage that we pretend to be nostalgic for. Easier to love than the Krays and jellied eels, harder than greyhound racing. Raymond himself was an unsympathetic character, a man with a failed mind-reading act who finally twigged what men were thinking about, and persuaded his beautiful assistant to take her top off for an extra ten shillings. He ended his days alone in his Mayfair eyrie, a shuttered sex-condo, counting his money. He was the Scrooge of Soho.

And yet the sight of his proud masthead in the night was absurdly transporting. How to account for the miracle on Rupert Street?

I could say that there’s a long and ignoble tradition of the bacchanal in midwinter, dating back to pre-Christian times and still honoured today in the office party. I could mention that some of our most dependable Yuletide tearjerkers are mired in the dark and the sordid: the suicidal Jimmy Stewart on the point of jumping in It’s A Wonderful Life; the squalid, heartbreaking romance of the Pogues’ ‘Fairytale of New York’. And Christ himself did not abjure the company of sex workers. But let me get a hold of myself: I’m talking about a sign here, not a Sign.

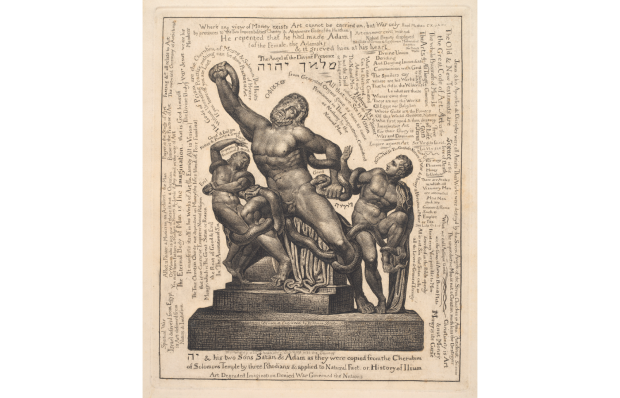

No, what struck me about the winking hoarding was its bonhomous acknowledgment of our common fleshy failings. It was like a righteous raspberry to the terrible puritanism of the attacks on Paris, a city condemned by IS as a ‘capital of prostitution and obscenity’. For a brief, delirious moment, Dick Bracey’s Babs or Joy might have been Marianne in Delacroix’s stirring (and similarly blouse-free) painting.

Of course, we are free to mark Christmas as we choose to, including not at all. That’s worth celebrating in itself. But just this once, we might overlook its consumerism, its regrettable excesses, yes, even its tackiness. That was what I thought when I gazed heavenward and, in ways undreamt of by C.S. Lewis, found myself surprised by Joy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

God’s Own Junkyard — My Generation is at Lights of Soho gallery until 23 January 2016.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in