Until a decade and a half ago, we had no national museum of modern art at all. Indeed, the stuff was not regarded as being of much interest to the British; now Tate Modern is about to expand vastly and bills itself as the most popular such institution in the world. The opening of the new, enlarged version on 17 June — with apparently 60 per cent more room for display — will be one of the art world events of the year. But, like all jumbo galleries, it will face the question: what on earth to put in all that space?

Essentially, there are two answers to that conundrum. Give the public what they want, or — alternatively — what you think they ought to see. Cynics might suggest that Undressed: A Brief History of Underwear at the V&A (16 April–12 March 2017) falls into the former category. And it looks very much as if the Royal Academy has also gone for the first option with Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse (30 January–20 April). This, of course, is just what a lot of people like to contemplate: pictures of flower-beds, in an impressionist idiom — and has already been pre-denounced as such. Personally, I’m rather fond of Monet — and of gardens too for that matter. So, for the time being, my judgment is suspended.

Opening later in spring upstairs at the RA In the Age of Giorgione (12 March–5 June) looks as if it might be one of the year’s highlights. Giorgione is one of the most elusive figures in art history. The list of facts we don’t know about him with any certainty begins with the year of his birth, and what he was called, apart from ‘Big George’. The late E.H. Gombrich once told me he thought Giorgione was the art-historical equivalent of an untreatable case: there was so much uncertainty about what he actually did that little can be said. Wisely, therefore, the RA is surrounding a few — in general estimation — authentic pictures by Giorgione with works by Giovanni Bellini, Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano del Piombo and others. The result may well be magnificent.

The National Gallery kicks off the year with Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art (17 February–22 May), which is one of those exhibitions — the Rubens extravaganza last year at the RA was another — which examine the effect an artist had on those who came afterwards. There will be pictures by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) but also by his distinguished fans, among them Manet, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin (so this may turn out, in part, to be an impressionist show in disguise).

Botticelli Reimagined at the V&A (5 March–3 July) aims to do something similar with the Renaissance Florentine master. It includes plenty by Botticelli himself — a tremendous favourite with the Victorians and ever since — but also works Botticelli-inspired by other artists, from Burne-Jones to Cindy Sherman. Simultaneously some of Botticelli’s drawings of scenes from Dante will be on display at the Courtauld Gallery (18 February–8 May).

Lucian Freud would not have enjoyed the last few exhibitions mentioned. He memorably described Botticelli’s art as ‘sickening’ and could not understand why Van Gogh preferred Delacroix to Ingres. However, he was a tremendous enthusiast for other varieties of 19th-century French art. The superb Corot, ‘Italian Woman’, which used to hang above his mantelpiece, will be the centrepiece of Painters’ Paintings from Van Dyck to Freud at the National Gallery (22 June–4 September). This is an exhibition about pictures that artists once owned, among them Van Dyck’s Titian and Matisse’s Degas. We shall have to wait and see whether the works on show have anything else in common.

‘Pegasus and the Hydra’, after 1900, by Odilon Redon

The risk with Beyond Caravaggio (National Gallery, 12 October–15 January 2017) is different. Again this looks at a hugely influential — and popular — master. The effect of Caravaggio’s revolutionary realism was immense in 17th-century Italy and throughout much of Europe. Here the danger is that his own paintings may make those of his followers look a bit dull, but that remains to be seen.

Over in the ever-proliferating Tate empire, the menu looks a good deal more austere. There is more emphasis on what’s good for us, and less on what we know we like. I must admit I’m slightly dreading the Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 at Tate Britain (12 April–29 August). Works that are not exciting or enjoyable to look at are my bête noire, and a good many of the exhibits in this will consist of nothing but text. However, Performing for the Camera (Tate Modern, 18 February–12 June), which is concerned with the way that artists have presented themselves in photographs since the 19th century, could be intriguing; it’s certainly an example of the avant-garde blazing a trail. Now the whole world, brandishing selfie sticks, is doing the same thing.

Painting with Light: Art and Photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Modern Age (Tate Britain, 11 May–25 September) takes a similar theme, but again quite a promising one. Painters tend to make good photographers, and — conversely — many photographers have striven to make their pictures look like paintings.

As the year continues, Tate exhibitions become more accommodating to the pleasure principle. The summer exhibition at Tate Modern is devoted to the American painter Georgia O’Keeffe (6 July–30 October) and will presumably contain almost as many modernist flowers — one of her most frequent subjects — as will be on show at the RA, albeit much more blatantly sexual blooms than Monet’s. In the autumn, a major show at Tate Britain is devoted to Paul Nash (26 October–5 March 2017), one of the most delightful British painters of the first half of the 20th century — though a decidedly uneven one. The question here will be how well his work stands up to the full retrospective treatment.

Over at the RA, there is an exhibition of new work by David Hockney, who continues to paint with extraordinary creative verve. The 79 Portraits and 2 Still Lifes (2 July–2 October) that will be included are just a portion of the work he has produced since 2013, and — the RA notes — the title is subject to alteration. The current total of 79 portraits, one guesses, might well increase.

The big autumn event at Burlington House is Abstract Expressionism (24 Septermber–2 January 2017) — another topic that is liable to draw the punters in throngs. Indeed, Rothko and Pollock are now almost as reliable box-office draws as Monet and Matisse, which demonstrates how over time the most outrageous of art may become mainstream. My only doubt is how well all those drips and splodges will look in the grand Victorian galleries of the RA.

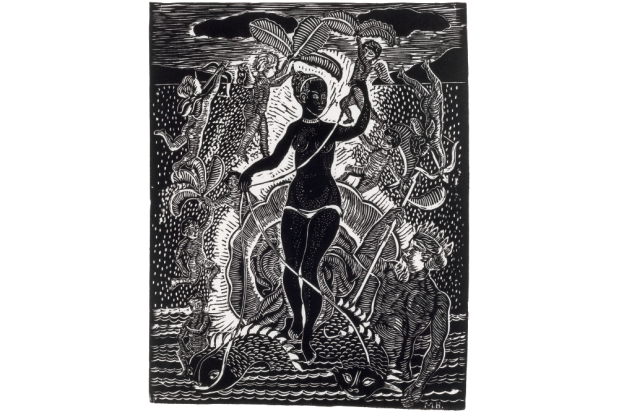

Back over at Tate Modern, there is Wifredo Lam (14 September–8 January 2017). A Cuban who evolved an Afro-Caribbean modernist idiom, Lam started off with the same sort of influences as Jackson Pollock (Picasso, surrealism). Towards the close of the year on Bankside there will be a fresh look at Robert Rauschenberg (1 December–2 April 2017), a prominent American artist in the 1950s and 60s whose reputation has slipped a little. He may well deserve a revival.

Finally, there is a change of director coming up at the British Museum, but Neil MacGregor’s extremely successful exhibition programme is set to continue, with two rich subjects tackled in early 2016. Sicily: Culture and Conquest (21 April–14 August) looks at an island that is a palimpsest of cultures, with ancient Greek, Islamic and Norman periods overlaying one another. Sunken cities: Egypt’s lost worlds (19 May–27 November) deals with more complex layers of civilisation — in this case ancient Egyptian and Hellenistic Greek — in sites recently explored by underwater archaeologists. That’s one reason why museums keep getting bigger: more art keeps appearing to put in them.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in