People tend to use the term ‘fashion victim’ somewhat damningly — and maybe jealously — to describe someone obsessed by the latest look. I’m not sure I agree. There’s something endearing about anyone who wants to dress in the newest style, and anyway, isn’t being up-to-date the whole point of fashion? It’s no more reprehensible than wanting the newest car, or iPhone, or flattest TV. ‘Victims’ are surely those who get it wrong — the mutton and lamb syndrome. More like what my beloved friend Melissa Wyndham called ‘fashion casualties’.

But now Alison Matthews David has brass-tackled the subject. In Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress, Past and Present (Bloomsbury, £25) she has shown in gruesome detail many fashions that did — and still could — hasten their wearers to an untimely death. We’ve heard about arsenic in St Helena’s green wallpaper poisoning Napoleon, but not that our Victorian forebears were swathed in the same toxic stuff, in clothes, shoes, feathers and artificial flowers. And who’d have thought that our parents’ boots were blacked with benzene treated with fuming nitric acid, which causes the extremities and lips to turn black from cyanosis — the very same concoction ‘used extensively in dry cleaning’.

In my youth, little girls in tulle dresses were always going up in flames, but its alarming to read that today’s rampant slogans on even the most respectable brands of T-shirts are made from nonylphenol exothalates that, when washed, leach deathly chemicals into the rest of your laundry.

If you sport your grandpa’s topper at Ascot, chances are it’s embedded with mercury, heralding ‘a pus-filled rash on the forehead’, or even ‘impeding your intellectual faculties’. And ladies, be wary of celluloid hair-combs, a popular eBay item. Our wall-of-glass windows magnify the sun’s rays, which can explode these recycled accessories into your scalp. Even the confidence-lending white coats of doctors harbour lethal bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, our old friend MRSA. Nanny was right about catching your death, and not only of cold.

Stitches in Time: The Story of the Clothes We Wear by Lucy Adlington (Random House, £16.99) is for geeks rather than victims; this informative journey through essentially workaday clothing and its more decorative elements tells how garments evolved and developed and why some have lasted. Its no-nonsense tone is slightly marred by weak puns (‘Reaching New Heights’ is a chapter on high heels). I looked in vain for a reference to the linsey-woolsey stuff of the Wee-Willy-Winky-style nightwear of my childhood, which I’m astonished to find one can still buy on eBay today. Must be safe as houses.

The Fine Art of Fashion Illustration edited by Julian Robinson and Gracie Calvey (Frances Lincoln, £35) reveals what great artists fashion illustrators really were, from the Renaissance onwards, until eclipsed by 20th-century magazine photographers. The details of dress in the author’s selection — simple, ravishing or ludicrous — are deliciously depicted, and show how close is the relation of painters to illustrators, particularly in the late 18th century and vice versa. Watteau’s nephew François-Louis-Joseph drew as exquisitely as his uncle; some figures on these pages could be by Boucher or Gainsborough, others recall the diaphanous ‘attitudes’ of Lady Hamilton, or knock spots off Tamara Lempika. It’s intriguing to look at these illustrations, each specifically dated, and picture their subjects in rooms — rustling silks in Kedleston, say, or stridently deco against Syrie Maugham’s all-whiteness — of the various periods.

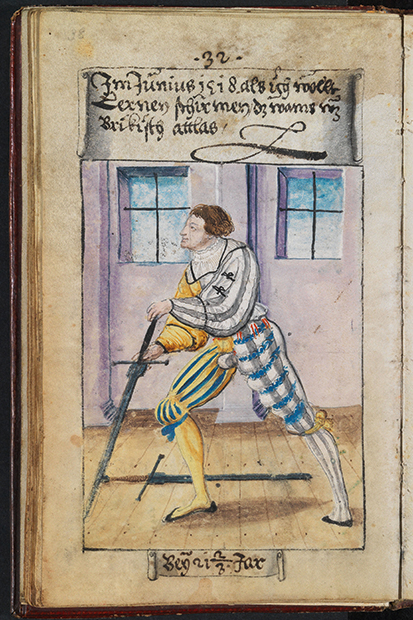

Matthäus Konrad Schwartz was born in Germany in 1497, becoming at the age of 23 chief accountant to the billionaire Fugger family, famous inventors of banking. His portrait by Hans Maler hangs in the Louvre. Though stylistically typical of the early 16th century, the degagé sable stole and multi-tasseled shirt strung with necklaces hint at a degree of dandyism.

As well they might. From the age of five, Matthäus had himself painted each time he ordered a new outfit. On parchment, with a printed text describing how and when and why he wore them, and what they were made of, they were bound into a miniscule (10 x 16 cm) book. This has now been enlarged by Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward into The First Book of Fashion: The Book of Clothes of Matthäus and Veit Konrad Schwartz of Augsburg (Bloomsbury, £30). It’s quite simply the most fascinating record of a ‘victim’ one could hope for.

In August 1518, for archery, Matthäus is in restrained monochrome, enlivened by gilded trellis-work hot-pants Liberace would’ve killed for, but by May 1521, he’s into scarlet ostrich feathers, and armour, over a red-stripe silk-satin onesie ‘to walk towards His Highness Ferdinand of Austria’, and beside it, handwritten, ‘The face is well-captured’. On May Day, 1528, he goes shooting in peach taffeta knickerbockers, the ‘doublet like gold and pearls sparkling’. By 1539, its ‘pure white half-silk’ top-to-toe, and, thriftily, it being only half-silk, he had ‘an identical black outfit made’.

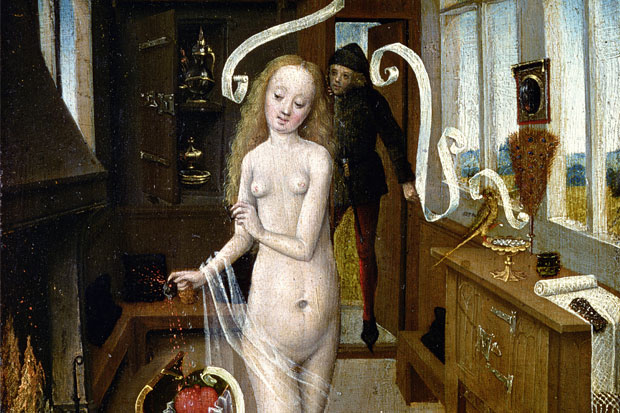

In July 1526 Matthäus is painted starkers, front and back views, as ‘my figure… had become fat and round’. It hadn’t, but it’s nice to see he wasn’t vain. And there were no flies on him either: his cod-pieces, spherical or upturned — he wore ‘the bag-style just once’ — are modishly adorned, and while his outfits become faintly more sober as he ages, his son Veit Konrad’s veer toward the prosaic.

The authors point out that many forms of new materials were flowing into Europe at this time and the mirror became more than a court luxury. Never has the mould of form been reflected in the glass of fashion so entertainingly as in this scholarly work.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in