Painters and sculptors are highly averse to being labelled. So much so that it seems fairly certain that, if asked, Michelangelo would have indignantly repudiated the suggestion that he belonged to something called ‘the Renaissance’. Peter Blake is among the few I’ve met who owns up to being a member of a movement; he openly admits to being a pop artist. The odd thing about that candid declaration is that I’m not sure he really is one.

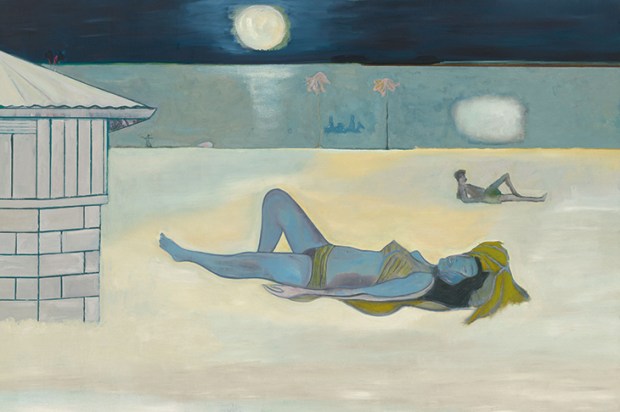

A delightful exhibition at the Waddington Custot Gallery presents Blake in several guises, including photorealist and fantasist, but — although one of the exhibits is an elaborate shrine in honour of Elvis Presley — ‘pop’ is not the term that comes to mind.

One reason why artists don’t like being classified is that the more those categories — baroque, impressionist — are examined, the more they fall apart. For example, Blake has genuinely ‘pop’ tastes in one sense: he is a fan of rock’n’roll — indeed famously created an album cover for the Beatles. But there is none of the irony of an Andy Warhol about his work, or the intellectual distance of Richard Hamilton. He comes across partly as a gentle realist, and partly as a romantic with a love of eccentric outsiders.

One half of the exhibition is made up of portraits, among them a fine one of Leslie Waddington, founder of the gallery, whose death was announced this week. Blake makes no secret of the fact that these are based on photographs, which he traces. Such a procedure has been common for centuries, but a superstitious feeling lingers that it is somehow ‘cheating’ to use a camera to help make a painting. But what Blake is doing is far more subtle than simply copying a photograph. His translation of the original image into paint is delicate and subtle — and sometimes requires an extraordinary amount of time.

Blake is renowned for continuing to exhibit certain pictures as ‘works in progress’ for decades (one in this exhibition was begun ‘c.1980’). If he can be very slow, however, Blake — now 83 — can also be surprisingly quick. Many of the exhibits in this show date from this year.

Among them is a series of new watercolours entitled ‘Tatooed Men & Women’ (see p33). They all have everyday faces, presumably derived again from photographs, but emblazoned on their skin is a whimsical phantasmagoria. One has a full crucifixion on his chest, plus the word ‘Mother’; a woman has portrayals of princes Harry and William across her naked breasts. These hark back to Blake’s long-standing love of fairground entertainers and what you might call contemporary folk art. So, too, does a series, still ‘in progress’, depicting fantastic wrestlers, each with a fighting pseudonym — ‘Considerate Boy’, ‘Princess Perfect’, written beneath their picture and a characteristic costume. Princess Perfect wears a crown to fight.

David Jones, subject of a retrospective exhibition at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, is also hard to place in any category. That’s about the only thing he has in common with Blake, except for origins on the south bank of the Thames. Blake hails from Dartford; Jones (1895–1974) was brought up in Brockley, the child of an Anglo-Italian mother and Welsh father.

The mixture in his life and work of medievalism, poetry, piety and modernism was perhaps — like some chemical compounds — inherently unstable. A poet and writer — T.S. Eliot described his book In Parenthesis, based on his experiences in the first world war, as a ‘work of genius’ — Jones was absorbed in a mental world of Arthurian legends and Celtic literature. At Camberwell School of Art he had absorbed the influences of Cézanne and later Picasso and Derain. In his 20s, he converted to Catholicism, and lived for a while in craft communities presided over by Eric Gill.

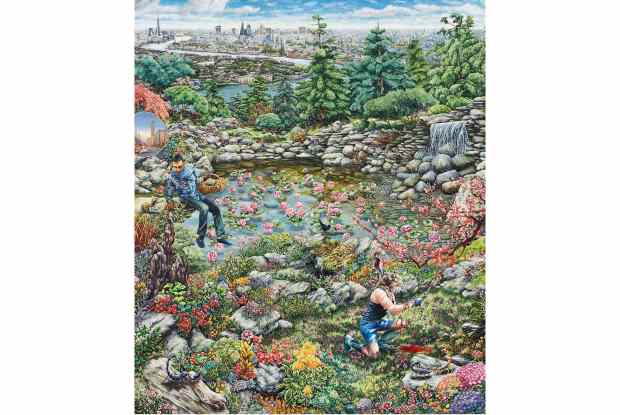

In Jones’s most dense images, such as ‘Aphrodite in Aulis’ (1940–1), there is a chaotic thicket of symbolic bric-à-brac in which you can make out a bulbous, naked goddess, soldiers from the first world war and fragments of Roman architecture. His wood engravings on religious themes, though more refined than Gill’s, still have a touch of art deco Romanesque about them.

Jones did much better when tethered to the real world by a subject such as a portrait or a landscape seen through a window (a favourite theme perhaps because Jones suffered from agoraphobia). Even then the results could be both muddy — as watercolour — and muddled; but when it came off the effect could be ecstatic.

In ‘Flora in Calyx-Light’ (1950) everything — not just glass but wood and stone — becomes translucent. Ostensibly this is a picture of three glass vessels filled with flowers on a tabletop in front of a window. But it’s simultaneously a mystic vision in which these solid objects appear to melt in front of your eyes.

This painting almost but not quite dissolves into a shimmering cobweb of fragments: leaves, tendrils, petals, reflections.

In a curious fashion this waywardly backward-looking man was completely of his time: ‘Flora in Calyx-Light’ is about the Holy Grail, but also close to Jackson Pollock. A teacher at Camberwell once announced, addressing the whole class, ‘You see, Jones leaves out everything — except the magic.’ That’s true of his masterpieces, and despite his inner complexities and contradictions there were quite a few of those.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in