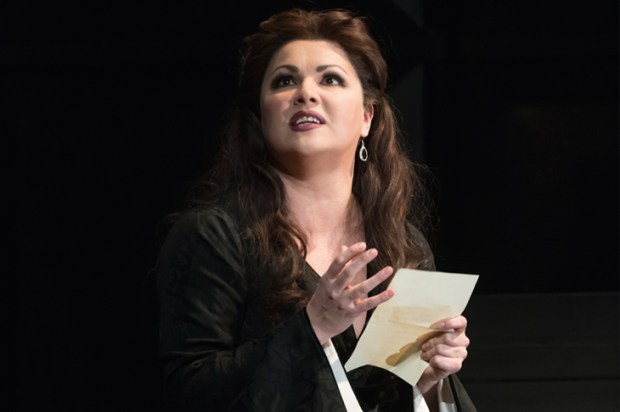

How often do you get a chance to see two operas by Leoncavallo in the same city in the same week? Never, until this last week in London, when Opera Rara gave a concert performance of Zazà at the Barbican, and six days later the Royal Opera mounted its first production since the 1980s of Cav. and Pag. Both Leoncavallo and Mascagni are routinely thought of as one-opera composers. Zazà didn’t do a lot to undermine that view, and I doubt whether if it had been staged it would have made any stronger an impression. Like Pag., its libretto is by the composer: Wagner seems to have made that temporarily mandatory. But the plot is feeble almost to the point of nonexistence. Zazà is a club singer who falls for one of the clients, finds out that he is married with a young teenage daughter, and so renounces him, though rather surprisingly no one dies. Zazà was sung by Ermonela Jaho, the Albanian singer who has made a worldwide reputation in La Traviata, on which this opera is clearly modelled. It’s a pity that the Barbican provided no scenery for her to chew, because if they had she would certainly have obliged. As it was she had only the music stand to wrestle with. Her performance was so intense, committed and indeed abandoned — and she does have a thrilling and powerful voice — that it was impossible not to be excited. How far the impression she made will survive transference to record remains to be heard. The whole performance, conducted by Maurizio Benini, as almost all performances of Italian opera anywhere are, was a model of precision and passion. The BBC Symphony Orchestra played their hearts out in an unrewarding score, and the excellent team of singers surpassed even Opera Rara’s normal high standards.

It’s just a pity about the work. Whereas one emerges from Pagliacci with several melodies surging through one’s head for hours or days, Zazà doesn’t sport a single memorable tune. It is also vastly too long, over two hours, quite a lot of which is shameless padding. The singer Cascart, an old flame of Zazà’s who is on hand to offer restraining advice, sings probably the best aria in the piece, and Stephen Gaertner rose imposingly to the occasion: it used to be a repertoire piece, recorded by many distinguished baritones on 78s. The married man with whom Zazà is infatuated was Riccardo Massi, a young tenor with a big future and already quite a past. His music is especially weak, and the enormous argument that he and Zazà have before she rises to renunciation is as long as such rows are in real life, and not half so much fun. I hope this thrilling performance didn’t put ideas into the head of any country-house opera director.

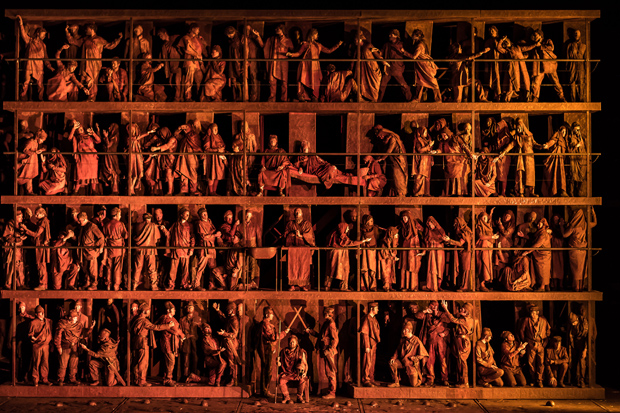

The director of the new Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci is Damiano Michieletto, the set designer Paolo Fantin, who created a sensation with Guillaume Tell. Nothing sensational about these two productions, which are set in and around a bakery (Cav.) and a theatre (Pag.) in Sicily in the 1980s, the eternal drabness and poverty of life being indicated by dull-coloured cardigans. Not a glimpse of the sun, though, and the tirelessly revolving sets seem to be in the void. Cav. came first, as always, and it’s a good thing it did, to get it out of the way for the enormously more rewarding Pag. Though you couldn’t complain much about the individual performances in Cav., the whole thing was musically too well mannered. Antonio Pappano drew refined playing from the orchestra, and the singers, again a strong cast, gave cultivated readings of their roles. But that’s just what Cav. doesn’t need. Listen to a recording from the Fifties or earlier, preferably a pirated live one, and you’ll hear just how vulgar this piece is — and also how exciting it is, so long as it is vulgar enough. Lovingly precise treatment kills it with respect, and that’s what makes this production so unaffecting. D.H. Lawrence, in the introduction to his translation of Verga, whose story provided Mascagni with his plot, says how much superior Verga is ‘to Mascagni’s rather cheap music’, and rightly calls him one of the greatest masters of the short story. The kind of satisfactions Verga provides are of course different from anything Mascagni could manage, not by being tasteful, but by achieving a rawness for which vulgarity is quite a decent substitute. There are plenty of memorable tunes in Cav., beginning with the prelude, including the Easter Hymn, the utterly irrelevant but adorable Intermezzo, and even the accompaniment to one or two arias, but they are not closely relevant to the action, at best providing local colour, but hardly doing that much. The characters are entirely generic — the philandering tenor, the deserted soprano, the vengeful husband — and Michieletto did nothing to make them more specific, so the results were equally unfocused, for all the enthusiastic and annoyingly frequent applause coming from the production team.

Pagliacci, by contrast, was wholly successful, a vindication of this maligned piece, in which the wonderful arias, Nedda’s bird-envying ‘Stridono lassù’ (which gets a virtual rerun in Zazà), Tonio’s ‘Vesti la giubba’, and so on give the characters an individuality as well as being archetypal. Aleksandrs Antonenko, whose Turiddu had been a bit dull, came to vivid life here as Tonio, and had clearly been saving himself. Carmen Giannattasio’s Nedda, passionate, nervous, frustrated, was one of the most moving accounts I have heard of this tricky role. Dimitri Platanias, a loutish Alfio in Cav., gave a stupendous performance of the noble Prologue, and then in the body of the work was quite loathsome, while the enviably named Dionysios Sourbis introduced some genuine sexiness as Nedda’s would-be lover Silvio.

There’s a lot more that could be said both about the admirable qualities of this production, and about the instructive superiority of this cathartic work to its companion, but here’s hoping it comes back again soon.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in