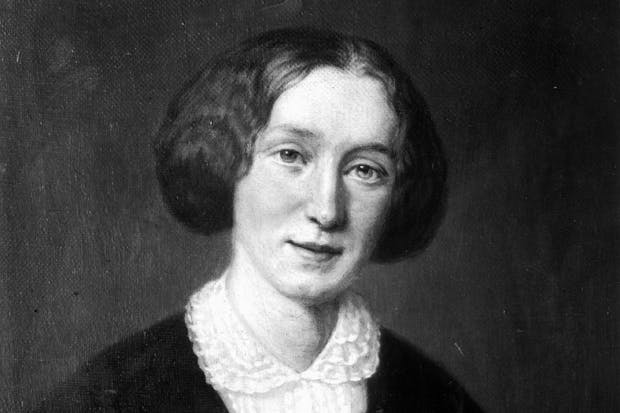

‘Fine old Christmas,’ wrote George Eliot, ‘with the snowy hair and ruddy face, had done his duty that year in the noblest fashion, and had set off his rich gifts of warmth and colour with all the heightening contrast of frost and snow.’

Thus opens the second chapter of Book II of The Mill on the Floss. I had found the passage when searching for a secular reading for my newspaper column’s readers at a carol service at St Bride’s church in Fleet Street a couple of nights ago. I knew at once I’d found what I wanted.

Eliot had been my first port of call. You can be confident she will avoid religiosity yet never take refuge in mere jollity. She is never pat. Not for her the ‘Deck the hall with boughs of holly, fa-la-la-la-la la-la-la-la’ piped merriment, content-light and designed to infuse supermarket shoppers of all faiths and none with a desire for more chocolate. Not for her the secular festivity calculated to put the X into Xmas. I knew she’d shy from that. I read on…

Snow lay on the croft and riverbank in undulations softer than the limbs of infancy … there was no gleam, no shadow, for the heavens, too, were one still, pale cloud; no sound or motion in anything but the dark river that flowed and moaned like an unresting sorrow.

As ever, Eliot’s descriptive flight of the imagination has an intelligent purpose which soon becomes clear. ‘But old Christmas smiled as he laid this cruel-seeming spell on the outdoor world,’ she writes, ‘for he meant to light up home with new brightness, to deepen all the richness of indoor colour… he meant to prepare a sweet imprisonment that would strengthen the primitive fellowship of kindred, and make the sunshine of familiar human faces as welcome as the hidden day-star.’ Her literary conceit is the idea that by leaching warmth and colour outdoors, old Christmas has enriched indoors. We snuggle closer together when it’s cold outside. A nice thought. But this is not enough for the greatest of our English authors, and perhaps a mite too cute. Can we really rest easy? Hasn’t old Christmas overlooked something?

His kindness fell but hardly on the homeless,—fell but hardly on the homes where the hearth was not very warm, and where the food had little fragrance; where the human faces had had no sunshine in them, but rather the leaden, blank-eyed gaze of unexpectant want.

Eliot does not answer this. Nor can I and nor can you. And it strikes me that that sense of a vast unanswered question marks Eliot out as the modern mind she is. Post–Reformation western society is unusual, isn’t it, in placing a great big ache at the heart of our moral reasoning?

I am no social historian of ethics and unsure who has ever answered that job description. There are of course textbooks. Philosophers have surveyed antique moral reasoning, and in our own age a Bertrand Russell, an A.C. Grayling or a Bernard Williams have essayed masterly surveys of the sweep of the history of moral science. Obsolete moralities and ethical systems have all been catalogued.

But where does this fit with a human history of what troubled people, what bygone cultures believed to be the big unanswered philosophical questions of their age? How complete, how fit for purpose, did the Romans or the Greeks suppose their systems of morals to be? When did Christianity begin to lose confidence (as I think it now has) that its teachings can offer a sure framework for day-to-day moral reasoning?

So sure was Aristotle that ethical questions were soluble by the application of logic and common sense that he could advise anyone seeking to determine the ‘right’ course of action to ask themselves what a respected gentleman would recommend; and if still in doubt ask what would be going too far, and would not be going far enough, and thereby locate the mean between them as the appropriate action. The Nichomachean Ethics do not speak to me of an age of aching uncertainty about the rules for human coexistence. From those times, only Pilate’s ‘what is truth?’ calls to us down the ages with a modern ring.

Early Christianity strikes me as inheriting much from Aristotle’s ‘think about it: it’s obvious’ approach. The Roman Catholic church added layer upon layer of specific rules, all underwritten by a claim to divine authority — the big ‘Because’ — as handed down by a clear and certain hierarchy of human office-holders. The Reformation at first aimed to replace Roman Catholic certainties with certainties of its own. But in time the Reformation produced so many competing answers to the big ethical questions that in the schisms, sects and splinters — the rival certainties — modern Europe’s sense of one great, shared moral certainty was lost.

Christianity has lost its bearings, as I’ve argued here before; but I don’t believe secular thinking has found them. The ache I describe — the lost chord — is (as, again, I’ve argued here) our failure to answer the question Christ himself never really faced up to, though He was asked it. ‘Who is my neighbour?’

Jesus appears to reply ‘Everyone’, but this is impossible as we cannot help everyone equally, and need an order of priorities. Who, and in what order? My elderly former secretary with severe dementia? The drug addict on the street? The migrant? The orphaned Syrian? Show us the mark and we’ll try to meet it, but we genuinely don’t know what to aim for, and no voice from our own age advises with authority. Who is our neighbour? This year’s agonising pictures of desperate migrants have sharpened the aching question in many western hearts.

George Eliot ends by wondering if old Christmas knows. He doesn’t.

But the fine old season meant well; and if he has not learned the secret how to bless men impartially, it is because his father Time, with ever-unrelenting purpose, still hides that secret in his own mighty, slow-beating heart.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in