It’s hard to imagine Christmas without stars. They perch at the top of fir trees, glitter from greeting cards and dangle festively over shopping precincts. This year, even the John Lewis advert and Selfridges’ Oxford Street window display — two of the holiest icons of our modern, commercialised Christmas —both have astronomical themes.

The origin of this celestial obsession is of course the Star of Bethlehem, whose apparition, according to the Gospel of Matthew, first alerted the Three Wise Men to the birth of Jesus, then guided them across the desert to pay homage to the new-born Messiah. For centuries scholars have speculated as to whether this founding tale of Christianity might have some basis in historical fact but, in an age in which religion and science are often caricatured as standing in stark opposition to one another, what are we to make of a book that uses science to investigate one of the Bible’s best-loved stories?

The title of The Great Christ Comet may give the impression that this is some sort of fire-and-brimstone religious tract. On the contrary, it is for the most part a sober, detailed and accessible account of both scripture and science — and perhaps the most comprehensive treatment of the Star of Bethlehem story to date.

Over the centuries many different types of astronomical phenomena have been invoked to explain the Star, and Colin Nicholl describes and assesses them all. The science of comets, supernovae and planetary conjunctions is explained, and their relative merits as objects that might have driven Babylonian astrologers to cross the deserts of the Middle East are clearly laid out. Since he is a Biblical scholar by training, Nicholl’s grasp of the essential astronomy and astrophysics is all the more impressive. But his cool and even-handed treatment of the science sits somewhat uneasily with the book’s fundamental assumption that the story of the Biblical star must have some basis in historical events, rather than being a shrewd (perhaps even expected) embellishment to the founding myth of a new religion.

Of course, the reliability of source material is an issue faced by historians and scientists alike. Drawing on modern Bible scholarship, Nicholl suggests that the stylistic and structural similarity of the Gospels to contemporary Greco-Roman biographies indicates that their authors, writing decades after Jesus’s birth, are simply reporting what they’ve heard with no attempt to add or embellish. But surely this is exactly the template the Gospel authors would choose if they wanted to convince prospective converts of their veracity?

Still, if we follow Nicholl’s lead and give the author of Matthew the benefit of the doubt, the book soon regains firmer ground. Here Nicholl’s background adds a new and extremely valuable dimension to the debate. Matthew’s statements about the Star, which often seem vague and confusing from a modern perspective, are re-examined in the context of astronomy and astrology as it was understood two millennia ago

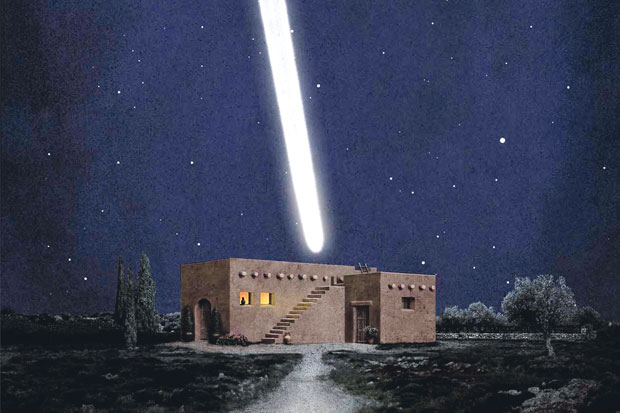

As the book’s title makes clear, Nicholl is convinced that a comet is the only class of object that can plausibly explain the details of Matthew’s description, as well as the astrological and religious significance accorded to the Star. Here 21st-century technology is deployed to impressive effect: Nicholl uses freely available astronomical software to calculate how such a comet must have orbited the Sun, allowing it to fulfil all of the key points of Matthew’s account, changing its appearance and position in the sky as the Magi travelled westwards across the desert in time to provide a spectacular show in the southern sky when they arrived at Jerusalem. Illustrations of historical comets from the last few centuries are used to show how Nicholl’s ‘Christ Comet’ might have appeared: if he is right, the scene in the sky above Bethlehem could have been considerably more spectacular than the twinkling point of light commonly depicted on our Christmas cards.

However, this remains a big ‘if’. The book’s arguments are detailed and often highly plausible but at certain points they rely on suppositions about the motivations and psychology of Biblical characters, and in the end we are asked to accept that one of the most spectacular cometary apparitions for millennia was recorded for posterity only by the Christians of first-century Judea. Nicholl is commendably upfront about the leaps of faith that he asks us to make, but there are places where his interpretation seems to draw on religious convictions that may not be shared by every reader.

Does it really matter whether the Star of Bethlehem was a real astronomical object or not? Read as a parable of hope and salvation, the Biblical account of the Nativity is a universal story: peace on earth and goodwill to all men is a message that even the most hardline atheist can get behind. The prominent inclusion of a stellar element to the tale reminds us that human beings have always looked to the heavens in order to gain a better understanding of life down here on Earth. Today, comets are scrutinised for signs, not of the birth of kings, but of the origins of life itself: right now the European Space Agency’s Rosetta probe is in orbit about the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, beaming back a stream of images and data that are revising our understanding of the formation of our own planet 4.5 billion years ago. The Magi would surely have shared our wonder at this technological miracle.

Nicholl’s thesis is one of the most detailed and compelling proposals to date, but it will surely not be the last. After two millennia the Star of Bethlehem continues to exert its fascination on the wise, and perhaps this tells us more about ourselves than it does about either the Bible or astronomy. If so, we will doubtless be following this particular star for millennia to come.

Book review — astronomy, St Matthew’s Gospel, the Three Wise Men, the Messiah, Judea, astrology, the Mag

Book review — astronomy, St Matthew’s Gospel, the Three Wise Men, the Messiah, Judea, astrology, the Mag

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

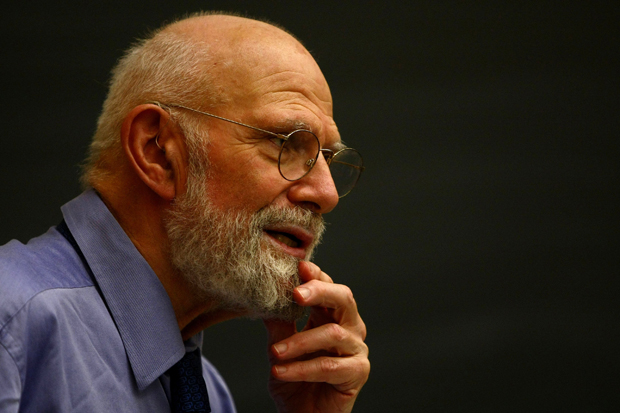

Marek Kukula is Public Astronomer at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £22. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in