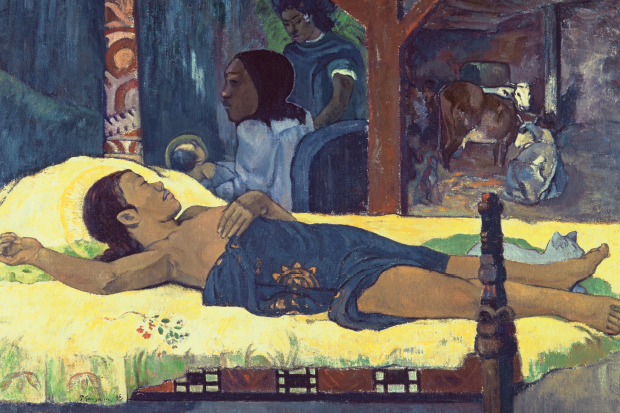

A young Polynesian woman lies outstretched on sheets of a soft lemon yellow. She is wrapped in deep blue cloth, decorated with a golden star. Beside her bed sits a hooded figure, apparently an older woman, holding a baby. In the background is a huddle of resting cows, suggesting that the setting is a barn or stable.

There is something familiar about the set-up — baby, young mother, farm animals — but it may take a while to notice certain details. The head of the woman on the bed is encircled by an area of darker yellow, which forms a sort of halo, and the baby’s head is similarly ringed with green. A subsidiary figure standing in the shadows has an odd protuberance, which looks a little like a wing. Then you realise that this is a painting of a most unusual kind: a Tahitian Nativity.

It was painted in 1896 by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), who inscribed the title at the bottom left of the canvas: Te tamari no atua, which means — roughly, since Gauguin’s grasp of Tahitian was shaky — ‘The Child of God’. But why should Gauguin have produced such an unexpected image of what might seem, for a dissolute adherent of the avant-garde, such a surprising subject?

A standard interpretation is that the picture is connected with the fact that the artist’s teenage Polynesian mistress, Pahura, gave birth around Christmas time in that year (the baby, a little girl, lived only a few weeks). However, the scholar George Shackelford has pointed out that the picture must have been one of those the painter dispatched by ship to Paris in July 1896, so, Shackelford concluded, at the latest it could have been painted in the early months of Pahura’s pregnancy. It is equally possible that it has nothing to do with Gauguin’s impending fatherhood; that he simply decided to paint a Tahitian Madonna because, in a highly unorthodox fashion, he was a man with religion on his mind.

There is a lingering impression that when Gauguin went to the South Pacific he painted and drew what he saw. This was not altogether so. Certainly, local people, landscapes and objects got into his work. The space in which ‘Te tamari no atua’ is set might be based on the house Gauguin built for himself in the village of Puna’auia, with walls of bamboo cane and a thatched roof of plaited palm leaves. The mother on the bed is presumably modelled on Pahura. But just as much Gauguin depicted what was in his head, and also in his luggage.

He came to Tahiti — sailing for the first time in 1891, returning after a period back in France towards the end of 1895 — with a travelling photographic library of visual sources. Among these were details from the 5th-century Greek Parthenon frieze and Buddhist sculptures from the Javanese temple of Borobudur. Poses and plants from the latter crept into an earlier Tahitian Madonna and Child, ‘Ia Orana Maria (Hail Maria)’, from 1891. This sort of cross-cultural cut-and-paste — south-east Asian forms, Polynesian setting, Christian subject — is typical of Gauguin.

He was attracted to the idea — in the air in the 1890s — that all the world’s religions and mythologies were essentially the same. In 1897 he wrote a long, rambling essay entitled ‘The Catholic Church and Modern Times’. In this Gauguin claimed that divinity was an ‘unfathomable mystery’. ‘God does not belong to the scientist, nor to the logician; he belongs to the poets, to the realm of dreams; he is the symbol of Beauty, Beauty itself.’

Gauguin’s behaviour at Puna’auia appalled the local priest, especially the artist’s installation of a large, nude female woodcarving outside his house. His liaisons with a series of young Polynesian women — Pahura was under 15 when their relationship began, and he was 47 — seem more profoundly abhorrent in the 21st century.

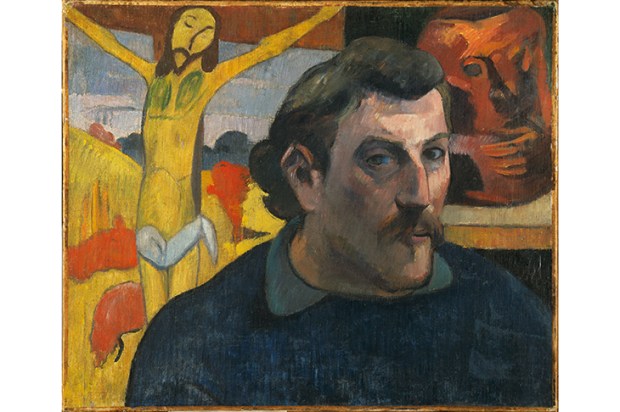

There is a touch of Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz about Gauguin’s last years, descending into the heart of darkness. As the art historian Belinda Thomson has put it, however, ‘If Gauguin was something of an immoralist, he was also something of a moralist.’ He once painted a self-portrait in which he wears a halo, but grasps the satanic serpent from the Garden of Eden between two fingers like a cigarette. His imagination was filled with Catholic imagery and doctrine, and had been from an early age.

At 11 he had become a boarder at the petit séminaire de la Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, near Orléans. There Gauguin underwent what he called ‘the theological studies of my youth’. He was taught by the Bishop of Orléans himself, Félix-Antoine-Philibert Dupanloup, an influential campaigner for religious education. The way that the Bishop’s instruction shaped the young artist’s mind is suggested by the questions Dupanloup posed in a text on the catechism. ‘Where does the human species come from? Where is it going? How does it go?’

The Bishop believed such rhetorical inquiries would linger in the pupils’ inner worlds, so that in later life, even if they were living irreligious lives and had lost their faith, ‘instinctively, instantaneously’ such questions would come into their consciousness. In the case of at least one ex-student he seems to have been correct. ‘Te tamari no atua’ is one of a sequence of splendid paintings that led up to Gauguin’s masterpiece of 1897–8. Its title, of course, was ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’

The Nativity was not the only Christian subject that Gauguin painted — he also tackled the Last Supper, the Agony in the Garden and the Fall of Man among others. But it was a scene he depicted several times. Evidently, it meant something to him. Indeed, Christmas was a significant season for Gauguin, connected with the birth of his beloved daughter Aline and the catastrophic breakdown and self-mutilation by Vincent van Gogh that ended the short but dramatic period during which the two painters shared a house in Arles.

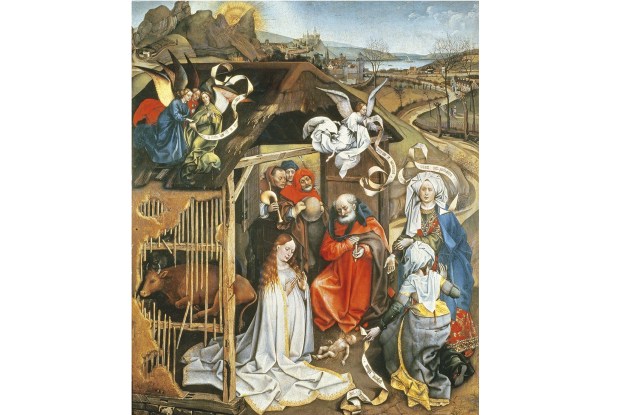

A hidden clue, I believe, links ‘Te tamari no atua’ to Van Gogh and the south of France. Its arrangement — Mary lying on a bed with folded coverlet, a seated figure beside her, cows in the background — is unusual but it is echoed closely in a carving on the Church of St Trophime in Arles. The superb Romanesque sculptures of this building — the most powerful works of art in the town — made a strong impression on Van Gogh, as we know from his letters, and apparently on Gauguin too. So perhaps this extraordinary tropical Nativity was triggered by a memory of medieval Provence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in