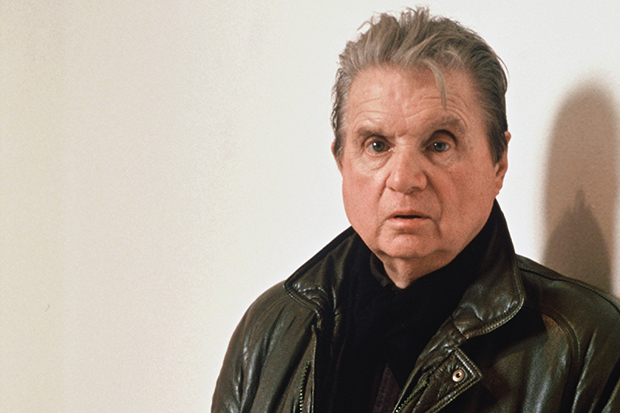

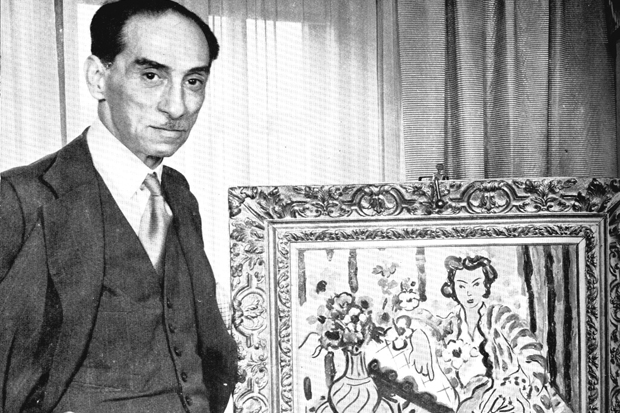

Bernard Buffet was no one’s idea of a great painter. Except, that is, Pierre Bergé and Nick Foulkes. Bergé was Buffet’s original backer and boyfriend, later performing identical roles for Yves Saint-Laurent, turning the sensitive designer into a global ‘luxury brand’ and turning himself into one of France’s richest men with pistonnage to spare. Foulkes is the accomplished writer on style who, in this new book, aims to rehabilitate an artistic reputation which he feels has been dissed by the narrow prejudices of the art-historical establishment.

To a degree, this is true. Because Buffet’s scratchy and splashy paintings are (mawkishly) ‘figurative’, he never satisfied the criteria of ‘relevance’ and ‘progress’ that dominated art history and art criticism in the second half of the last century. He was mocked by Paris intellos, whose leader, the Napoleonic minister of culture, André Malraux, was committed to promoting abstraction. As a counter-attack, Buffet’s supporters invented a rivalry with the much older Picasso when, more accurately, Picasso’s attitude to the younger man was majestically disdainful. Rather like Britain’s special relationship with the US, this rivalry was felt on only one side.

But the Buffet story is fascinating. At a commercial level, his success was enormous. And his pictures satisfied a certain need: a Buffet image of, say, a depressed pêcheur recalls a moment in time as precisely as a tangerine-coloured Arne Jacobsen chair or a Renault Floride. What we have in The Invention of the Modern Mega-Artist is a case-study of the conflict between high and low culture, the uneasy bargain between popular acceptance and critical acclaim. Buffet never pleased serious critics, but today we are more inclusive. Categories and frontiers of art history are being reconsidered, so Buffet deserves reappraisal. But it’s a tough job: everyone agrees that he was a faiseur (a poser) who caricatured the idea of a modern painter on a stage managed by the French media.

If the conventional view of Buffet was that his pictures of weeping clowns are ham-fisted, coarse and sentimental, executed with modest skill, the very definition of low-brow, a shallow art requiring no interpretation or effort by the viewer, then it is up to his new champion to make an alternative case. That’s the dynamic of this big, interesting book. Foulkes thinks it was merely snobbery that denied Buffet esteem but, in fact, it was taste. There really is such a thing, and it is always worth cultivating. Just because a majority of critics and experts agree does not mean they are wrong.

Foulkes is fascinated by the oddities of the beau monde and has found in Buffet an excellent subject. The painter had a superb genius for self-invention and self-promotion. He married the actress Annabel Schwob, but was gay when it suited him. He lived in Manosque with Bergé and Jean Giono, the myth-maker of Provence, for 18 months. Identities came and went. Before he was 30, he had abandoned the ragged smock of the suffering artist and was ‘roulant en Rolls’. His Rolls-Royce became a stock motif in magazine commentaries.

Buffet was a part of the Saint-Tropez scene, including Françoise Sagan, Johnny Hallyday and Brigitte Bardot, so lionised by Paris Match. He became rich, but remained ‘maudit, incompris et mal aimé’ (cursed, misunderstood and unloved). Still, this was perhaps the last moment when a living painter seemed important. When he died in 1999, as a result of a suicide involving a plastic bag, Le Figaro gave him ten pages.

Foulkes has drowned himself in the subject and done impressive research, including interviews with Juliette Gréco and John Richardson, the distinguished Picasso expert. It’s Richardson who explodes the plot, describing Buffet as ‘a fashionable mannerist whose work pleased rich bourgeois people who wanted to look perhaps more sophisticated and modern than they were’. It was ‘flashy’. Worse, it was ‘chic’. Perhaps the same can occasionally be said of Foulkes himself.

He always has interesting things to say, but too often his sophistication slides into lazy journalese. ‘Eponymous’, ‘the likes of’ and ‘veritable’ are words that never need be used. Years are ‘ensuing’, Parc Monceau is ‘upmarket’, Monaco is a ‘small Mediterranean principality’: that, I am afraid, is just padding. There are other Homeric formulae: Saint-Laurent is the ‘bespectacled couturier’.

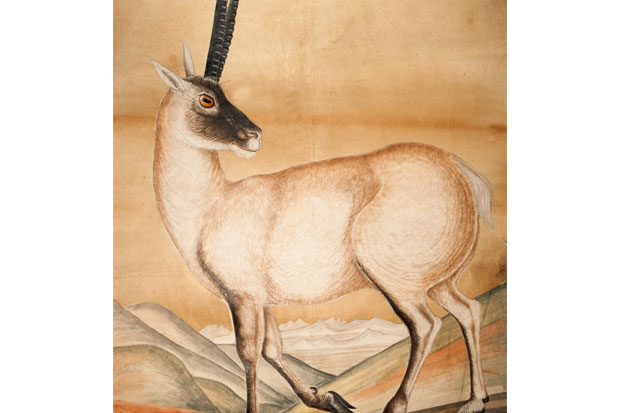

The Invention of the Modern Mega-Artist can be enjoyed, but its ultimate value cannot easily be separated from the worth of its subject. To be honest, don’t we all recognise that Dufy and Utrillo are second-rate when compared to say, Matisse and Picasso? And how deeply, pitiably inferior is Buffet to Dufy and Utrillo! Yet Buffet styled himself as their successor.

He manufactured paintings in a studio lit by electric lights. His chosen medium of oil paint was anachronistic. Of fresh observation there was none. He despised intellectuals perhaps because they possessed ideas he lacked. He was all front and no bottom. Comparing Bernard Buffet to Pablo Picasso is like comparing Val Doonican to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Let’s be frank, Buffet was kitsch. And kitsch means fake.

This is a bold and stylish attempt at revisionism, but ultimately the subject and the author have neither the materials nor the equipment to re-build the reputation of this junk artist.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £21 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in