For years, I’ve wondered why so many clever people go to Davos to discuss topics as meaningless as ‘the new global context’ or ‘shared norms for the new reality’. It has always struck me like a massive game of Just A Minute, in which contestants compete on how long they can talk about a theme that makes no sense at all. But as I found out when I visited last week, the real game is far more sophisticated. No one at Davos cares too much about the gabfest. The debates are, in effect, a front for the biggest networking event in the capitalist world.

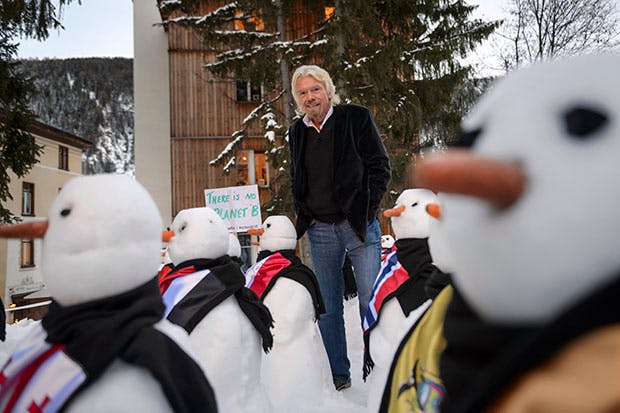

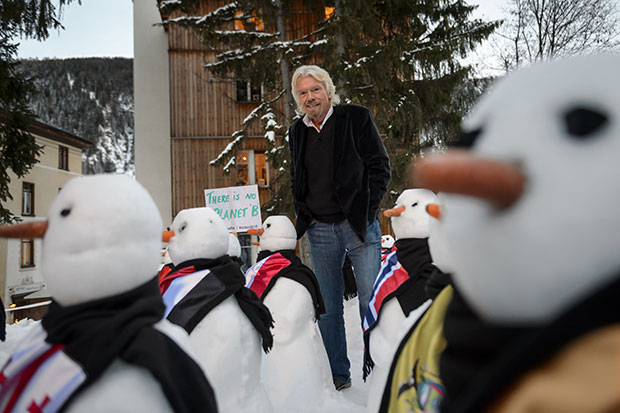

For one week, this ski resort becomes a fortress guarded by the Swiss army. Venture capitalists chase chief executives, who chase the politicians while the journalists chase everyone. There are so few decent hotels in Davos that there’s nowhere for anyone to hide. Much of the talk was about the stock-market crash, which is troubling the attendees. One of them, I found out, is Sir Richard Branson. ‘My God,’ he said, as he sat down for breakfast on a table behind me, ‘a lot of net worth down the drain in the last few weeks. But not to worry, I suppose it will come back eventually.’ His visitor arrived, and started a Dragon’s Den-style pitch for a business plan. I averted my ears.

On my first evening, I ended up in a funicular railway car next to Chuck Hagel, until recently US Defence Secretary. I asked him about the bombing campaign against the Islamic State and he wasn’t optimistic. Their greatest weapon, he said, was their ability to recruit — not just bored idiots from Bradford, but qualified doctors and gifted computer hackers. When will it end? ‘Not for years,’ he said. ‘The Islamic State is an ideology. And you can’t bomb an ideology.’

Prices at Davos are adjusted to suit the customers: I’m not sure I’ll ever recover from paying £52 for a burger. A search for cheaper food (and beer) took me to a tavern on the edge of town, where I was served a hideous white sausage. I got talking to a German policeman who works part-time as a chauffeur, driving Swiss billionaires around. His story was more interesting than any I heard at the summit. ‘The Islamic State is everywhere in Germany,’ he said, and it was his job to spy on its sympathisers. He was, in effect, a member of a new Stasi. Each jihadi in Germany is monitored by a team of 12 officers, who check on their suspects for about a day a week. It works so well, he said, that the chances of a terror attack on German soil are almost nil. He cites two factors: the ‘stupidity’ of German jihadis and the quality of German espionage (‘As a country, we do surveillance very well’). Forget Deutschland 83. It’s clearly time for a remake of The Lives of Others.

On the flight back from Zurich, a strange sight: Robert Peston enjoying the first-class luxury of seat 1C while Justine Greening, Secretary of State for International Development, shuffled past him on her way to economy. ‘I’ll send you back a glass of champagne,’ said a passenger in business class. ‘Only if it’s a full glass,’ she replied.

FOR THE FIRST TIME in its history, St Andrew’s School in the east end of Glasgow is about to send a pupil to Oxford — quite a feat, given that it serves one of Britain’s most deprived communities. There should, of course, be no link between poverty and attainment, but an iron law governs our state schools: the kids from the poorest neighbourhoods always get the worst results. It’s a formula that keeps inequality running through the generations, and one which the Social Mobility Foundation is trying to do something about. The foundation offers help and mentoring to super-bright kids from deprived backgrounds — such as Jack Wands. Thanks to the SMF, he spent two weeks with JP Morgan, then was sent to Oxford for a day in the hope that he might apply. He did, and was offered a place reading politics, philosophy and economics.

I hear about Jack’s success at an SMF meeting. The Spectator has been taking its brilliant interns for years (we’ve hired two) and I’m now a trustee. But as I found out, there’s a problem. The SMF has teenagers of incredible quality, but there are not enough businesses willing to offer internships — especially in the worlds of finance and science. So what to do? How to pull in the favours on the behalf of those with no contacts?

The answer is simple. Readers of The Spectator are perhaps the best-connected and most warm-hearted people in the world. Together we can nobble anyone we might know in any position of influence and persuade them to welcome a few SMF interns for a week or so. It may not save Britain from being run by PPE graduates, but it may help ensure a better quality of PPE graduate.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in