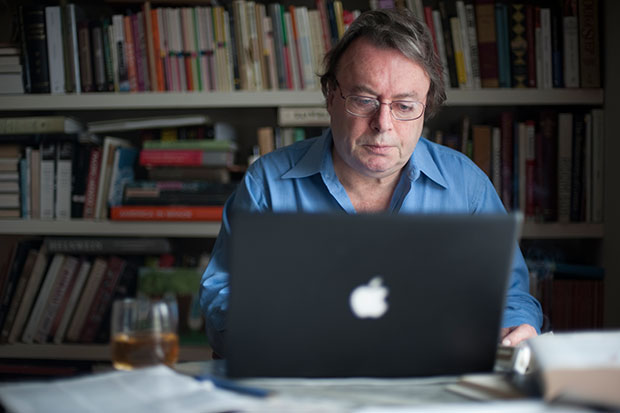

Jack Shenker is a throwback to an older, more romantic age when foreign correspondents were angry, partisan and half-crazed with frustration at the stupidity of the powerful. He made his name in Egypt, arriving with nothing more than a desire to be a reporter. As the revolution began, he moved to Tahrir Square and started to publish stories in the Guardian. He soon began to win awards, notably for a piece on the deaths of African migrants in the Mediterranean. He has continued to report around the world, but his first love remains Cairo. The Egyptians, his first book, is fuelled by anger and frustration. Shenker was there at the dawn of the revolution, lived through the disappointment of the Muslim Brotherhood’s election victory, and is now a witness to the counter-revolution that brought the brutish Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to power.

There is plenty of reason to be angry in post-revolutionary Egypt. About the only person who still lauds the coup is Tony Blair, who Shenker finds working with Sir Martin Sorrel’s WPP to rebrand the latest dictator-led Egypt. Since seizing power, the generals have outlawed political parties, cancelled elections, sent every notable revolutionary to the organised rape centres that double as prisons in Egypt, and are now presiding over a total economic collapse. Shenker wants to find light in this tunnel and argues that the spirit of resistance has not been crushed. He points to graffiti artists, techno DJs who play the local style known as magharanat, volunteers who combat sexual abuse at demos and an online debate forum, Salafyo Costa, which could be translated as Salafists Enjoying Coffee. Shenker recognises his examples are quite slim, however, and the book is coloured by lost hope.

Anyone lucky enough to break out of the Cairo of pyramids, bakshish and perfume shops will discover one of the world’s great cities. When the revolution began, a BBC reporter declared that Cairo had never before experienced the exuberant scenes taking place behind her in Tahrir Square. I had been there on the night in 2010 when Egypt beat Algeria 4–0 in the semifinal of the Africa Cup and knew that she was wrong. Cairo is an intense and crazy place, so when Shenker looks for signs that a radical spirit still exists, one wonders if he is merely seeing the everyday buzz of Cairene life.

Egypt’s problems are obvious enough. It has no law and order, no functioning state institutions and no real government. The police and army are self-serving mafias, and the only way to secure a job and hope to make a living is through patronage and bribery, so there is no point in wasting money on training or education. The country is sinking into inertia, with low skills, outdated industries and no tax base.

The long-serving President Mubarak relied on gas, tourism and revenue from the Suez Canal, all of which are failing for different reasons. Thirty years’ worth of attempts to reinvigorate industry through privatisation and competition, angrily dismissed by Shenker as ‘neo-liberalism’, have failed because state-owned companies simply became private monopolies, immune from risk and with no incentive to modernise. As Shenker notes, one cause of the revolution was the discovery that Mubarak was selling gas to Israel below market prices, which caused consternation as much as outrage: here was a man who could not even steal competently.

Any book on Egypt today would be crippled by dismay. No one could blame Shenker for failing to rise above his disappointment, but perhaps it skews his analysis. He focuses only on Egypt, ignoring the wider revolutions that give Tahrir Square its immediate context, without offering any specifically Egyptian reason as to why the revolution happened when it did. Instead, he presents a Manichean struggle between two entities he dubs Mubarak Country and Revolution Country, as though they are opposing eternal forces. Already, Mubarak feels too outdated to explain much at all. In Shenker’s account, Mubarak’s great crime was to sell off Egypt to the global economy, a process he dates back to the transition from Nasser to Sadat. One might feel that Sadat deserves more charity, at least for steering an autonomous course by breaking with Russia and reversing Israeli war gains.

Shenker’s book gains power when he reports on events; for instance, the horrific account of the techniques used by gangs of rapists to drive women away from the big demos. Yet his analysis of the revolution and its failure never goes beyond his rage at global capitalism. At this level of abstraction, no person or group is really to blame for Egypt’s parlous state, but nor is it possible that anything will ever change. One hopes someone, somewhere, has an analysis that contradicts this pessimism. Egypt may be a basket case, but anyone who knows the country falls in love with it. To believe it is beyond salvation is too heartbreaking to contemplate.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £13.49. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in