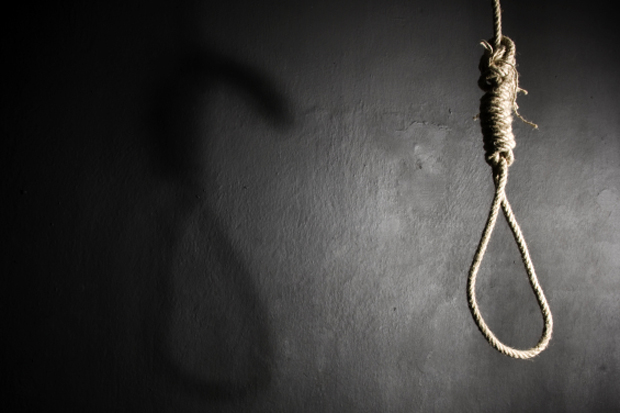

It begins with a sketch. We’re in a prison in 1963 where Harry Wade, the UK’s second most famous hangman, is overseeing the execution of a killer who protests his innocence. The well-built convict effortlessly shrugs aside two burly but incompetent prison officers. ‘I’m being hanged by nincompoops,’ he laments. One of them helpfully points out that if he’d followed his instructions he’d ‘be dead by now’. Do these arch quips make you quiver with mirth? If so you’ll enjoy Hangmen, a slapstick comedy thriller by Martin McDonagh.

The scene shifts to Oldham in 1965. Capital punishment has been abolished and the retired Wade has taken over a pub in his hometown where he enjoys the status of a minor celebrity. Unsurprisingly for a professional slaughterman, Wade is a mountain of bullying insecurity who loves to humiliate those closest to him. He harries his slinky wife, his chubby teenage daughter and his all-male team of regular boozers who keep his tavern in business. This chorus line of alcoholics exchange the sort of aimlessly silly dialogue pioneered by Pinter. When a flash southerner named Mooney barges in and starts to ingratiate himself with Wade’s family the sluggish plot starts to take shape. Mooney is a criminal maniac who plans to abduct and perhaps to kill Wade’s daughter.

The performances, especially from Johnny Flynn as Mooney and Andy Nyman as Wade’s deputy Syd, are quirky, absorbing and often very funny. McDonagh’s vicious, caustic dialogue sparkles like broken flints. ‘Babycham man’ (to mean gay) has an authentic ring to it, but it may well be the author’s invention. Elsewhere a few anachronisms creep in. Hearing characters in 1965 say ‘combo’, ‘teen’ and ‘back in the day’ is like seeing Lady Macbeth telling her husband to ‘pop the knives in the dishwasher’.

The play’s climax articulates the perils of false accusation with respect to capital punishment but it does so with an Ortonesque piece of slapstick rather than with a personal ordeal or a moment of dramatic suffering. And having reached this peak, McDonagh can’t push the fun any further so he throws in a cameo from Albert Pierrepoint whose renown Wade has always envied. He physically shrinks in the presence of Pierrepoint, who comes across as even nastier and touchier than his junior colleague. And here McDonagh shows his limitations. Pierrepoint simply becomes Wade and he in turn becomes the querulous Syd. Some commentators have recorded their admiration for the play’s structure. I’m not so sure. There seemed no reason for Mooney to return to the pub at night having cruelly insulted the landlady there a few hours earlier. My guess is that he had an unbreakable appointment with the playwright. Likewise the fate of Wade’s daughter left me scratching my scalp. But a macabre slice of knockabout like this needn’t meet the highest standards of logic in its construction. It’s good fun, a bit disturbing and ultimately forgettable.

Nine Lives opens with a bearded African alone on stage next to a battered suitcase and a pair of gold high heels. He’s Ishmael, a gay Zimbabwean, on the run from his homophobic countrymen and offered a new home on the Burnsall Heights Estate near Leeds. The authorities take ages (and ages) to process his asylum request and in the meantime we get to know the claimant. He’s a decent, unremarkable chap who might have pursued a life of blameless tedium as a milkman, a lepidopterist or a philosophy lecturer if only he’d been born in Britain. But exile has made him a reluctant martyr. He’s dissatisfied with everything. His bed is broken; his landlady is discourteous; the locals insult him; he finds purchasing food with vouchers humiliating. His readiness to complain makes him an unfortunate poster boy for the asylum system. Is it so dreadful that he’s asked by immigration officials to describe how a penis feels? Most men, gay or straight, are happy to disclose their thoughts on this topic at inordinate, and perhaps even wearisome, length.

Lladel Bryant, a skilful actor with a powerful stage presence, seems to have landed a plum job with this play. Although billed as a monologue, the script reaches out beyond its principal subject and becomes a quaint series of Yorkshire pen portraits. We hear from gossiping waitresses, impatient till girls, sinister street bullies, chatty mums at the swings. Actors love an opportunity to ‘show their range’ with a plenitude of voices and impersonations but the sheer variety here harms the focus of the piece. Ishmael’s predicament becomes a minor doodle in a sprawling municipal frieze. And the play appears to accept the bizarre notion that every setback and slap-down suffered by an asylum seeker is an indelible stain on Britain’s moral integrity. Here’s the crucial point: the guy had somewhere to escape to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in