On the face of it, the Netflix documentary serial Making a Murderer should only take up ten hours of your life. Judging from my experience, though, its ten episodes will prove so overwhelmingly riveting that you’re going to need at least two more days to scour the internet in an obsessive quest for every scrap of information about the Steven Avery case — and several evenings to discuss it with any fellow viewers you can find.

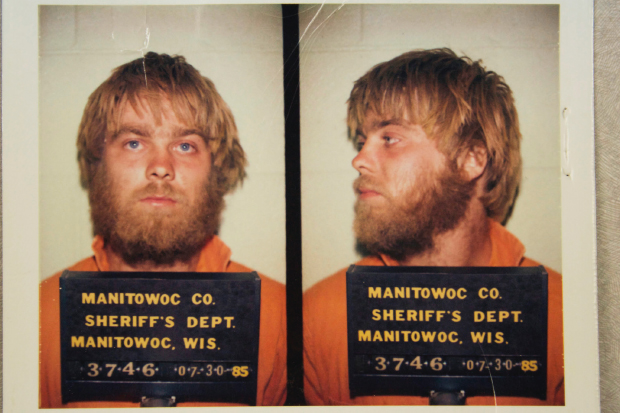

If the fuss about the series has so far passed you by (and if it has, it probably won’t for much longer), you may have to trust me that the story it tells — through such unspectacular old-school methods as assiduously researched footage, talking heads and the occasional caption — is from real life. In 1985, Steven Avery, of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin was arrested for a particularly violent rape. The sheriff’s department made few bones about how much they disliked Steven and his extended family, who lived in trailers on a nearby scrapyard and were clearly (and perhaps not inaccurately) regarded as white trash. The local police suggested that a known offender called Gregory Allen might also be worth investigating, but the sheriff and his men took no notice and continued with their successful mission to ensure Avery was convicted.

After 18 years protesting his innocence in prison, Avery was freed in 2003, when improvements in DNA science meant that the rapist was revealed to have been Gregory Allen. Once released, he then set about suing the sheriff’s department for $36 million — until he was arrested and charged with the murder of 25-year-old Teresa Halbach.

This time, the evidence appeared rather more convincing: Teresa’s charred remains were found near his trailer, drops of his blood in her car, and her key in his bedroom. Not only that, but his 16-year-old nephew Brendan gave the police a hair-raising account of how he and his uncle had raped and killed her.

But was everything quite as it seemed? Why, for example, had the key been discovered only on the seventh search of Avery’s bedroom, even though it was lying on the carpet? And why was the discovery made by a member of the Manitowoc County sheriff’s department, who shouldn’t have been there at all, given that the department had agreed not to take part in the investigation while Avery was suing them? Why, too, did a test tube of Avery’s blood, stored in the local crime lab since his rape case, have a small hole in its sealed top as if somebody had extracted some of the contents with a syringe?

Most strikingly of all, episode three shows us the police interview that led to the confession by Brendan, who has an IQ of 70. Without a lawyer present, Brendan was relentlessly badgered to tell the cops what they wanted to hear — and when after several failed attempts he finally did, he was visibly relieved to have got the right answer at last. Later, his mother asked him how he came up with his lurid story, which he was now denying. ‘I guessed,’ said Brendan. ‘That’s what I do with my homework too.’

In fact, this confession was ruled inadmissible at the televised trial (and, as it turns out, gripping courtroom drama) that found his uncle Steven guilty. But it was the centrepiece of Brendan’s, which despite having the same prosecutor giving a completely different account of Teresa’s death, also returned a guilty verdict. Both men have been protesting their innocence in prison ever since.

Admittedly it might not seem like it, but I’m only scratching the surface here — because this is a documentary heroically unafraid of painstaking detail, rightly confident that its audience will be hooked by the endless twists that a close-up approach can provide.

According to Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, who filmed the series over ten years, their chief aim was to expose the shortcomings of the justice system, and above all its indifference to that dreary old presumption-of-innocence business (an indifference, as we saw, firmly shared by the American media). But, while this aim is triumphantly achieved, less persuasive is their claim that Making a Murderer doesn’t commit itself either way on the question of whether or not Steven and Brendan actually committed the murder. Instead, with the defence lawyers cast in the role of Atticus Finch pitched against some of the nastiest sheriffs since Robin Hood’s day, there’s never any doubt which side we are supposed to be on. (Hence those growing online demands for Steven and Brendan’s release — and for the prosecutors’ heads on a platter.)

And that, for all the programme’s brilliance, does remain an awkward problem. Because it’s such an irresistibly powerful watch, you do end up desperately wanting to believe it — and therefore, strange to say, hoping that two innocent men really were stitched up by a fantastically vicious police conspiracy. Unfortunately, that obsessive internet search through the blizzard of theory and counter-theory suggests the story might be even more tangled than Making a Murderer leads us to think — and that it may have missed out some inconvenient facts. If so, of course, this doesn’t make the series any less fascinating to watch, think about or discuss. Nonetheless for anybody who holds to the quaint notion that documentaries should as far as possible be true, it would still represent something between a disappointment and a serious betrayal.

But now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Google more about the reliability of scientific tests that try to establish whether blood comes from a fresh wound or a crime-lab test tube…

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in