Listen

There are times when Westminster’s obsession with US politics is embarrassing for even the strongest believer in the Anglo-American relationship. Monday was one of those days: MPs debated banning Donald Trump, the reality TV star turned presidential hopeful, from entering Britain. Leaving aside the illiberal absurdity of this, Trump hadn’t even said he was planning a visit. It was a pathetic attempt by MPs to insert themselves into the US presidential race.

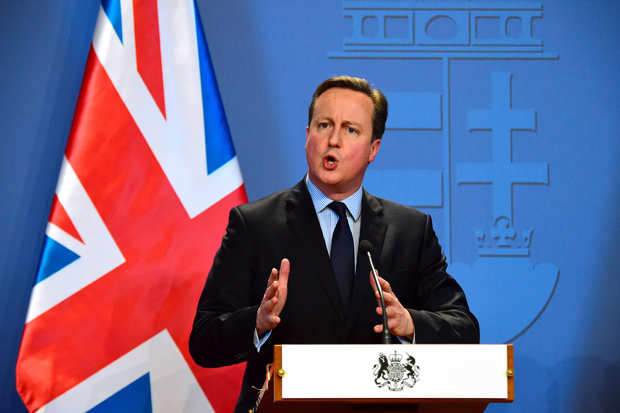

But what cannot be denied is the extent to which Trump is shaking up US politics. After the angry Republican primary and the failure of establishment candidates to gain traction, David Cameron’s achievement in winning a majority at the general election and holding his party together seems remarkable. He now has a good claim to be the most successful centre-right politician in the western world.

It is not only in America that the right is in crisis. In Canada, Stephen Harper’s government was defeated by Justin Trudeau. In Australia, the Tony Abbott experiment has been brought to an end by his own party. New Zealand’s John Key is the only other centre-right leader in the English-speaking world who can claim to be a success now.

The troubles of the centre-right aren’t limited to the Anglosphere. Angela Merkel has plunged her continent, her country and her chancellorship into crisis with her refugee policy. The tensions it has created within her party have the potential to do long-term structural damage to the German centre-right. In France, despite François Hollande’s unpopularity, polls suggest that Nicolas Sarkozy would be knocked out in the first round of the presidential election.

So, why is Cameron succeeding when other centre-right leaders are not? In part, it is because the British economy is continuing to grow and create jobs. The economic recovery means that there isn’t the same level of anti-establishment rage in Britain as there is in the United States.

But Cameron has also benefited from something that looked like a failure at the time, the split on the right. When senior Republicans visited London after their party’s 2012 defeat, the sense was that despite the loss, their long-term outlook — with the insurgent Tea Party wing still inside the party — was better than that of the Tories. It had seen members go off to join Ukip and the right was divided for the first time in British political history. Senior Tories feared that this analysis was right; that Cameron’s legacy would be a split that would leave the Tories struggling to ever again win a majority under the first-past-the-post system.

Ultimately, this split benefited Cameron. It helped the Tories become more attractive to centrist voters. On polling day, they gained more votes from those who supported Labour and the Liberal Democrats in 2010 than they lost to Ukip. It also meant that Cameron wasn’t trying to sound as angry and as frustrated with modern Britain as these defecting voters.

In contrast, all the Republican contenders in this primary season are trying to find ways to connect with the angry mood of their selectorate. Even Marco Rubio, the most mild-mannered of the candidates, has felt obliged to talk about how the gun he purchased on Christmas Eve is the ‘last line of defence between Isis and my family’.

In some ways, Britain’s centre-right is simply an election cycle ahead of other countries in terms of dealing with the challenge posed by insurgent parties. The current concern in Merkel’s CDU about the threat posed by the AfD — the Eurosceptic, anti-immigration party — in the forthcoming state elections mirrors the worries in Tory circles about Ukip in the middle of the last parliament.

But Cameron also deserves credit for keeping his head when others lost theirs. His refugee policy has been both humane — concentrating on those in the camps rather than those with the resources to get to Europe — and politically sustainable. Merkel’s has been neither. Given Cameron’s success, it is puzzling that more politicians aren’t seeking to emulate his model. In part, this is because he isn’t interested in going around the world selling his approach. There was no post-election victory lap of addresses to US think tanks and the like. George Osborne, by contrast, is far keener on the global political circuit.

Another reason is that Cameron has turned on its head Mario Cuomo’s dictum that you campaign in poetry and govern in prose. Cameron’s election campaign was well executed. But not even he would have called it exciting. Instead, he emphasised — and endlessly repeated — simple, clear arguments about economic competence, leadership and the need for a majority government. There was little talk of the social reform agenda which Cameron now hopes will be his legacy.

Watching him campaign in 2015, few would have imagined that his party conference speech five months later would concentrate on the need for ‘true equality’, an ‘all-out assault on poverty’ and the need to celebrate the ‘proudest multiracial democracy on earth’. Indeed, much of what makes the Tories so politically interesting wasn’t trailed in that campaign. Think, for instance, of George Osborne’s living wage, announced in his post-election Budget.

This new Tory agenda is designed to help the party appeal to new voting groups and to add a sense that the Tories share voters’ values. This might seem like common sense. But the Republicans are engaged in almost exactly the opposite exercise during this primary season. The candidates are indulging in ever more shrill rhetoric on the immigration question, to the despair of those concerned with the future of the party.

The dire state of the centre-right around the world should worry the Tories, even though they are the exception to it. Today, successful political parties rely on borrowing and adapting ideas from other countries. Many of the policies that the Tories are pursuing have their roots overseas — compassionate Conservatism comes out of the US, free schools from Sweden and prison reform from Texas. An international centre-right with a closed mind will not be much use to the Tories when they need to renew themselves, as every political party has to, at least once a generation.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in