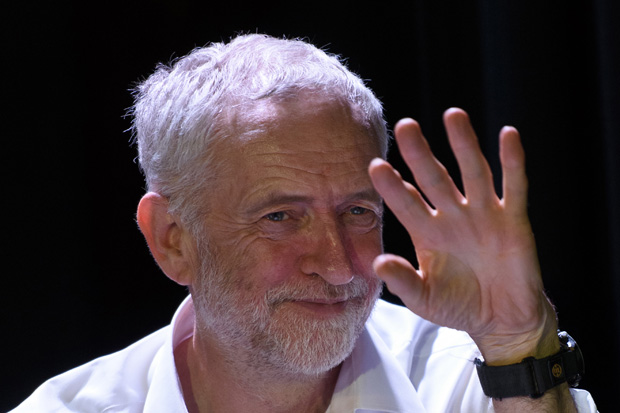

How much longer can the liberal left survive in the face of growing scientific evidence that many of its core beliefs are false? I’m thinking in particular of the conviction that all human beings are born with the same capacities, particularly the capacity for good, and that all mankind’s sins can be laid at the door of the capitalist societies of the West. For the sake of brevity, let’s call this the myth of the noble savage. This romanticism underpins all progressive movements, from the socialism of Jeremy Corbyn to the environmentalism of Caroline Lucas, and nearly every scientist who challenges it provokes an irrational hostility, often accompanied by a trashing of their professional reputations. Indeed, the reaction of so-called free thinkers to purveyors of inconvenient truths is reminiscent of the reaction of fundamentalist Christians to scientists who challenged their core beliefs.

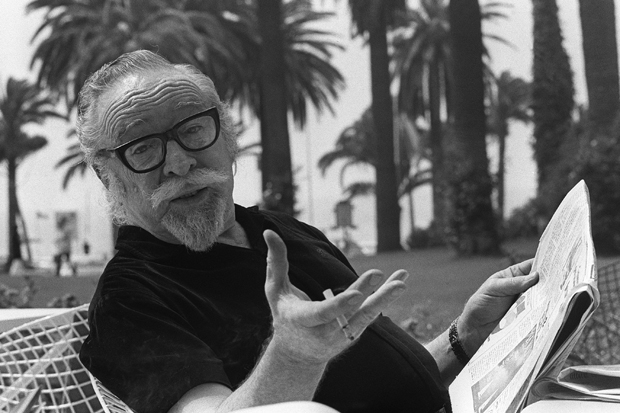

One such Charles Darwin figure is the American anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon. He has devoted his life to studying the Yanomamö, indigenous people of the Amazonian rain forest on the Brazilian-Venezuelan border, and his conclusions directly challenge the myth of the noble savage. ‘Real Indians sweat, they smell bad, they take hallucinogenic drugs, they belch after they eat, they covet and at times steal their neighbour’s wife, they fornicate, and they make war,’ Chagnon told a Brazilian journalist. His view of the Yanomamö people is summed up by the title he gave to his masterwork on the subject: The Fierce People.

Chagnon is a key figure in a new book by Alice Dreger, an American academic who has spent the last few years investigating attacks on heretical scientists by the grand inquisitors of the left. Dreger used to be something of a Torquemada herself. To defend the interests of people born with both male and female genitalia, she used many of the same questionable techniques to discredit opponents in the medical establishment. Then, in her words, she became ‘an aide-de-camp to -scientists who found themselves the target of activists like me’.

In 2000, in a book called Darkness in El Dorado, the journalist Patrick Tierney accused Chagnon and his collaborator James Neel of fomenting wars among rival tribes, aiding and abetting illegal gold miners, deliberately infecting the Yanomamö with measles and paying subjects to kill each other. Shockingly, these charges were taken at face value and widely reported in liberal publications like the New Yorker and the New York Times. (A headline in the Guardian read: -‘Scientist “killed Amazon Indians to test race theory”.’) Many of Chagnon’s colleagues turned on him, including the American Anthropological Association, which set up an task force to investigate. Chagnon was not allowed to defend himself and this task force published a report ‘confirming’ several allegations. As a result, Chagnon was forced into early retirement. In her book, Dreger summarises the thought crime that turned him into such a plump target: ‘Chagnon saw and represented in the Yanomamö a somewhat shocking image of evolved “human nature” — one featuring males fighting violently over fertile females, domestic brutality, ritualised drug use and ecological indifference. Not your standard liberal image of the unjustly oppressed, naturally peaceful, environmentally gentle rainforest Indian family.’

In a 50,000-word article published in 2011 in a peer-reviewed journal, she painstakingly rebutted all the charges against Chagnon, detailing the various ways in which Tierney had fabricated and misrepresented the evidence. Chagnon has now been exonerated and resumed his career.

Dreger has not abandoned her own liberal convictions. She believes the search for scientific truth and social justice go hand in hand and ends her book with an plea to academic colleagues to defend freedom of thought. But her title, Galileo’s Middle Finger, suggests the progressive left may not survive these clashes with heretical scientists. In comparing Chagnon to the Italian astronomer, she implies that the church of progressive opinion will face the same fate as the theologians who insisted the Earth was the centre of the universe. Eventually, the truth may prove too much. I recently interviewed Steven Pinker, the Harvard psychologist, and he’s confident that the liberal left can survive without the myth of the noble savage. I’m not so sure.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Toby Young is associate editor of The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in