One of the epigraphs to Peter Davidson’s nocturne on Europe’s arts of twilight is from Hegel: ‘The owl of Minerva begins to fly only at dusk’, an image of philosophy as posthumous, able to explain things only after we have experienced them. Or an image of dusk as threshold, the blue hour when light transforms itself, and other worlds become possible.

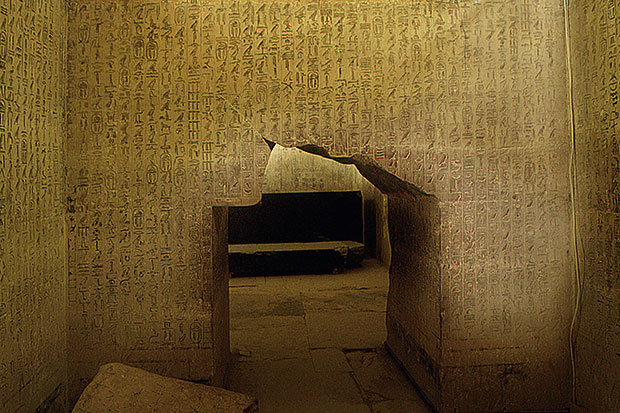

The Last of the Light is a cultural companion to such notions. A cabinet of curiosities — paintings, poems, music — framed by the idea of Europe as an archipelago of regret, many of whose most vital artefacts have dealt in echo and obscure longing, translated into a feeling for light. This is a trail going back to Virgil, poet of shadows, or else starting from Christian ideas of a crepuscular fallen world. The motif of ubi sunt is that we were always too late, that European culture is an enfilade of rooms, each opening forwards while looking backwards, in what Davidson calls ‘serial nostalgias’.

It is a theme rather than a subject, and he traces its variations in a patent blend of memoir, evocation of place and cultural itinerary. Davidson’s recent excursions into this terrain (his earlier book The Idea of North was a mixed-media exploration of nordicity) have been increasingly personal in register. This too is a book of the north, necessarily — long twilights only occur between the 50th and 70th parallel — rather than of places and latitudes where the sun drops like a stone.

It is also a declaration of allegiance to lost causes and shadowy histories: the landscapes of Catholic recusancy (Lancashire, the Herefordshire marches, northeastern Scotland) or the Jacobite north; Anglican ritual, the arts of the Stuart court, English Baroque in all its forms. There is a wistful affinity with minor masters, silver ages and fins de siècles, as opposed to ‘shining’ moments of cultural belonging or imperial confidence. We are drawn into dark and forgotten corners: draughty churches at ‘smokefall’ (T.S. Eliot), the 1930s world of the Shell Guides and their tutelary spirits Rex Whistler and John Piper. Or shabby postwar England, before the builders moved in, when this island was still a congeries of provinces linked by A-roads, as depopulated as a Ravilious watercolour. Whatever has suffered ‘modernist obloquy’ belongs potentially in the underworld of twilight.

The Last of the Light attends to the mood, rather than the spirit, of the age — whatever the age. The focus shifts back and forth, freewheeling between texts and images. Perhaps too freely, as if there were no differences of kind to be negotiated, no friction. It is in many respects an anthology of quotations, held together by virtuosic descriptive passages. But rather than clinching what he has to say, or relieving us of our certainties (as quotations should), the poetic instances he chooses are often inertly illustrative, windows onto his meanings. The prose quotations likewise raise difficulties, since he isn’t able to give them enough space to establish atmosphere.

Oddest of all is the books’s intermittent impulse to memoir — as evocative drapery, concealing as much as it reveals, rather than providing a narrative. Twilight is the world of what is unsaid or half-said, of shared obliquities between unnamed friends who appear at the edges of vision. We find ourselves in Andalucia at one point, but only learn why in an endnote: Davidson’s grandfather was Honorary Consul for the Anglo-Spanish community of sherry merchants at Cádiz in the 1920s. If only we had been told more. There is altogether too much trailing of suggestion by a farouche autobiographical presence. W.G. Sebald is one of the book’s presiding spirits, and the Sebaldian ‘I’ is an unfortunate influence, the prose at once fastidious and vague.

Equally the loose workings of association. Disparate figures from different periods are conflated, on the same pages, without transition. Their affinities are not argued into place but ‘come to mind’. Works prefigure or recall or echo each other;

Tiepolo resonates with the Danish low-light master Hammershoi, John Sell Cotman is not unlike Caspar David Friedrich. In this museum without walls the connections are finally too tenuous and personal.

Twilight is an uninvestigated essence, and we learn little about the political and ideological dusk that might lie beyond poem or picture. What we are offered instead are the changes rung upon that static and unaccountable thing, sadness. Thus ‘the fathomless sorrow of Victorian England’ is invoked as a given, but there are no explanatory connections as to what made it so — no reference, for example, to Victorian science and its stupefying news from nowhere. All is attributed to the waning of affect.

What this book displays finally is a pathology rather than a sensibility — plangent, marinated in melancholy and compelled to repeat itself. The Last of the Twilight is itself a work of belatedness, an exhibit in its own cabinet. It seems at first like a heroic solo attempt to re-enchant the world from a surprising angle. But the effect is something else: a sense that what we have lost is lostness itself. The hiding places have been run to ground, in the amnesiac glare of an implied present, beyond the hearing of history. As if there are no thresholds left to cross, no looking glass through which to be translated, no more twilight.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in