It’s often said that there are only seven basic plots in literature. When it comes to biographies of rock stars who died young, by contrast, there’s usually just the one: somebody mysteriously talented emerges from an unlikely background to achieve stardom, before being destroyed by drink, drugs and fame. Yet, as the film Amy proved last year, it’s a plot still capable of packing a real emotional punch — and, as Cowboy Song proves now, the life of Phil Lynott from Thin Lizzy embodies it more vividly than most.

Certainly, there’s no faulting the unlikeliness of his background. Lynott was born in 1949 to an Irish teenager who’d come to Birmingham in search of adventure, and found it in the shape of a Guyanese bloke who cleared off soon after the birth, apparently at her request. For the next seven years, she and Phil lived together in England — although even the assiduous Graeme Thomson can’t always be sure whereabouts — before she sent him to Dublin to be looked after by her parents. One of only four black children in the city, Lynott patiently allowed classmates to stroke his exotic hair and sometimes raided the collection boxes the school had for ‘black babies’ on the grounds that he was one of them. His main response to arriving in Ireland, however, was to make himself as Irish as possible.

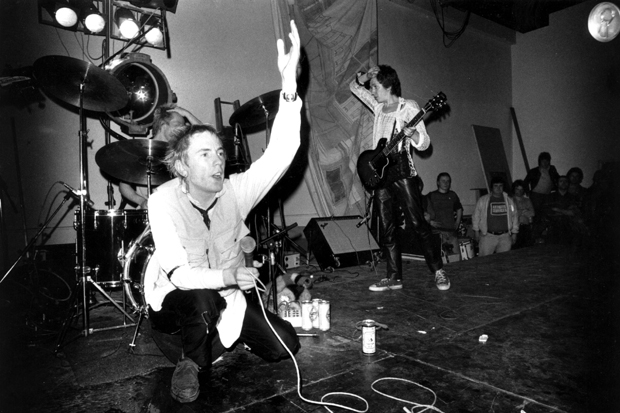

After singing in various Dublin bands as a teenager, Lynott formed Thin Lizzy when he was 20 and already established enough to insist on being the boss. By 1976, their stirring blend of macho rock and heartfelt lyricism had gained them mainstream success ,and with the indisputably great ‘The Boys Are Back in Town’ high in the US charts, the band looked poised to crack America — until Lynott was diagnosed with hepatitis and the tour there had to be abandoned. When it was rearranged, guitarist Brian Robertson wounded his hand in a bar fight just before they were due to go.

Such a run of bad luck might have driven anyone to drink. Lynott, though, was there already: his alcohol intake supplemented by more or less any drugs he could get his hands on (which, given that he had his dealers on a retainer, was more or less any drugs). In 1978, Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen became regular house-guests (never a good sign) and the following year he recorded the anti-drug lament ‘Got to Give It Up’ with a joint in one hand and a brandy in the other, snorting lines of cocaine between takes.

Anybody on the quest for these kind of rock’n’roll tales certainly won’t feel let down by Cowboy Song — even if, as an authorised biography, it tries hard to let Lynott off the hook whenever possible. His classic combination of pathological jealousy and astonishing promiscuity, for example, is put forward as evidence of a vulnerable and sensitive nature — including by some of the girlfriends involved. Nonetheless, if Thomson does occasionally pull his punches, he cunningly leaves enough space between the lines for us to imagine what those punches might have been.

Nor does he spare us the details of Lynott’s decline. Despite its persuasive closing claim that, as the country’s first ever rock star, Lynott is now ‘an Irish folk hero’, complete with a statute in Dublin city centre, the book’s final section makes for harrowing reading. After Thin Lizzy spilt up and his wife Caroline (who supplies a regretful and faintly exasperated afterword here) left him, taking their children, Lynott ill-advisedly toured with a new band, sometimes playing to fewer than 50 people. Heartbreakingly, he still began every gig by shouting, ‘Is anybody out there?’ — a question that once guaranteed a reliable roar from thousands of fans, but was now being asked at venues where the answer was essentially ‘No’.

In 1985, the year before his death, Lynott felt badly betrayed when his old friends Bob Geldof and Midge Ure didn’t ask him to play at Live Aid, considering it a deliberate snub. In fact, the real reason was perhaps even more wounding than that. The thought, Ure tells Thomson, ‘never crossed our minds’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £18.00. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.