Listen

http://rss.acast.com/viewfrom22/fightingovercrumbs-euroscepticsandtheeudeal/media.mp3

There are, as adman David Ogilvy remarked, no monuments to committees. (That’s not quite true; Auguste Rodin’s ‘Burghers of Calais’ — you can find a version in Victoria Tower Gardens — is somewhat collectivist in subject matter.) But there are certainly abundant monuments to the committee mentality, the bureaucratic spirit and art-world groupthink. That is what most contemporary ‘public art’ amounts to.

You will have seen ‘public art’ if you wander through developments of luxury apartments on, say, the southbank Thames littoral between Lambeth and Battersea. Or on a progressive university campus anywhere. Sometimes public art is plonked on ring-road roundabouts in bleak development areas whence true inspiration and authentic industry have long since fled. Public art may be hard to define, but it is always easy to detect: shrieking for attention, but pitiably inarticulate. Brash rather than brave. Assertive but dumb. Ham-fisted rather than skilful. Often expensive too.

It’s a travesty since it almost always fails to win public acceptance and, at the same time, fails any reasonable test of what art might actually want to be. It satisfies only (a) corporate or municipal egos who commission the stuff to expiate their sweaty generalised guilt; (b) Section 106 of the 1990 Town and Country Planning Act, which gives property developers a break if they can demonstrate a ‘planning gain’; or (c) the ambitions of an exclusive clique of ‘art consultants’ or for-hire curators and their client artists groomed only to respond to the narrow disciplines of (a) and (b).

The Spectator’s What’s That Thing? Award for bad public art is the result of a year-long scrutiny of this pollution that is settling so balefully on the townscape. The aim is not to thwart creativity, nor to mock enlightened patronage. Nor is it intended to inhibit, through anticipatory fear of shame, any future initiative that contributes anything beautiful or thoughtful to public life. Instead, rather as Alfred H. Barr explained the purposes of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, What’s That Thing? simply wants to be resolute and conscientious in the distinction of quality from mediocrity. Modern public art can be magnificent: witness, Richard Serra in Broadgate. With this in mind, we can now name the very worst recent examples of public art in Britain.

Though ranking the candidates was as difficult as determining the precedence between lice and fleas, our bottom five is led, indisputably, by Dashi Namdakov’s ‘She Guardian’ on Park Lane. Second is Andy Scott’s ‘The Steelman’ in Ravenscraig, North Lanarkshire. Third, Simon Periton’s ‘Alchemical Tree’ in Oxford. Fourth, Simon Fujiwara’s ‘Modern Marriage’ in the Nine Elms crypto-linear park. Fifth, Hamish Mackie’s ‘Horses’ in Goodman’s Fields, Aldgate, in the City.

Namdakov, recipient of the High State Award of Mongolia, is a member of the Russian Union of Artists and his work often displays a residual influence of the blustering, flatulent stuff once favoured by dictators in and beyond the Soviet Union. Indeed, his ‘She Guardian’ replaces an earlier essay inspired by Genghis Khan. But, as if to avert charges of tyrannophilia, Namdakov’s catalogue also includes sculptures of pussy-cats dozing on tree branches that would be at home in a giftshop in Alfriston. At least Hitler’s Arno Breker had original genius.

Clockwise from top left: ‘The Steelman’ by Andy Scott; ‘Horses’ by Hamish Mackie; ‘Alchemical Tree’ by Simon Periton; ‘Modern Marriage’ by Simon Fujiwara

Clockwise from top left: ‘The Steelman’ by Andy Scott; ‘Horses’ by Hamish Mackie; ‘Alchemical Tree’ by Simon Periton; ‘Modern Marriage’ by Simon Fujiwara

Claiming a relationship to Mongol folk tradition, Namdakov’s work is also, apparently, rooted in the iconography of Raymond Briggs’s Fungus the Bogeyman and Dungeons & Dragons. Muscles ripple, fangs do whatever fangs do. The occasional Buryat oligarch checking into the Dorchester for a Chinese meal and a Moldovan hooker might experience a pang, but this is (or was; it is currently on temporary loan to Tatarstan) a grotesque, inappropriate and embarrassing intrusion into London. Namdakov’s agent is the Halcyon Gallery, which has some unexplained arrangement with Westminster Council to showcase its lower-middlebrow rubbish.

Andy Scott’s ‘Steelman’, which is meant to celebrate the lost industrial arts of the Motherwell region, is programmatic in a wearily literal way. Without nuance or subtlety, ‘Steelman’, which makes not even a half-hearted play towards the observer’s higher faculties, succeeds only in mocking what it was intended to honour. The original northern iron and steelmen worked with practical and imaginative bravery in a new medium. A better client with a better artist might have made a tilt at appropriate novelty, poetry and soul. Instead, poor Ravenscraig has been given two-dimensional socialist realism in nursery-school style.

In Oxford, Simon Periton’s ‘Alchemical Tree’ is very different in that it is a three-dimensional illustration of a tortuously contrived programme that has a connection to the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter where it is sited. He is a man much concerned with sites, as so many public artists tend to be, ‘site-specific’ being the current term for what was once called an installation. Periton’s conceit of mottoes draped in an ash tree is, and I feel a stupefying wave of ennui as I write this, ‘a symbol connected with …interdisciplinary collaboration’.

Rather different is Simon Fujiwara’s ‘Modern Marriage’, a gigantic amputated foot in the lee of a mountain range of overdesigned but insensitive apartments. Fujiwara, a Cambridge-educated architect, occasional cellist and full-time erotomane, is a credible figure, at least by the lights of Frieze and its wordy defences of artists-who-defy-categorisation. Indeed, he was selected for this site by the god-like curator Norman Rosenthal who, briefly returned to earth, has now, perhaps not in vain, swapped allegiance from Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Royal Academy to Sean Mulryan’s Ballymore Estates. The public viewer, with no access to Fujiwara’s elaborate intellectual context, nor to Rosenthal’s lofty tastes, sees only something gross and horrible.

Meanwhile, Hamish Mackie’s ‘Horses’ is neither better nor worse than the sort of thing you see in the gardens of certain aspirational French hotels with one Michelin star, where animal sculpture and nymphs with pert nipples serve to distract customers from very expensive dinners. You want animal sculpture? Try Rembrandt Bugatti. You want an opinion on Hamish Mackie? Read André Derain, who suggested looking hard at nature, trying to reproduce it and then asking yourself if you are an imbecile. Put it this way: Mackie is no Bugatti and that’s a pity for the public in Aldgate.

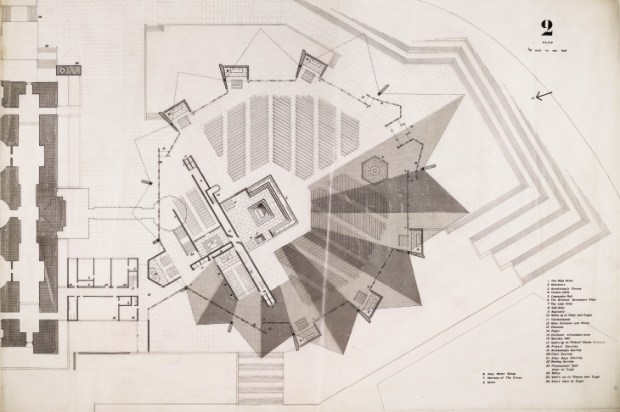

The results of the inaugural What’s That Thing? Award synchronise, in a way Jung might have understood, with Historic England’s Out There exhibition at Somerset House (until 10 April), an elegiac account of lost Festival of Britain Skylons, stolen Hepworths and Henry Moore’s charming ‘Old Flo’, which Tower Hamlets simply could not wait to get rid of. The long moment of the postwar settlement was a good one for public art. Heartbreaking efforts such as Victor Pasmore’s wonderful Apollo Pavilion at Peterlee New Town may have caused riots and been systematically vandalised by the public in whose name it was made, but the Forties, Fifties and Sixties at least offered a coherent raison d’être for the art: the edification of the public — the one Orwell described as having ‘mild knobby faces’ and ‘bad teeth’. This purpose has been replaced by we know not what.

But What’s That Thing? also coincides with the Prime Minister’s announcement of a Holocaust memorial to appear close to Rodin’s ‘Burghers’. What might it be? The great thing about the bad art of Namdakov, Scott, Periton, Fujiwara and Mackie is that it tells us what good art should be. It should never be dull or patronising. Nor should it excite sniggers or groans or winces. Good art can be difficult, contradictory, demanding and disturbing. It can be harrowing, beautiful or soothing. It should never be boring. And when you see it, you want more of it. That’s the ultimate test that the winners of the What’s That Thing? Award for bad public art all failed dismally.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in