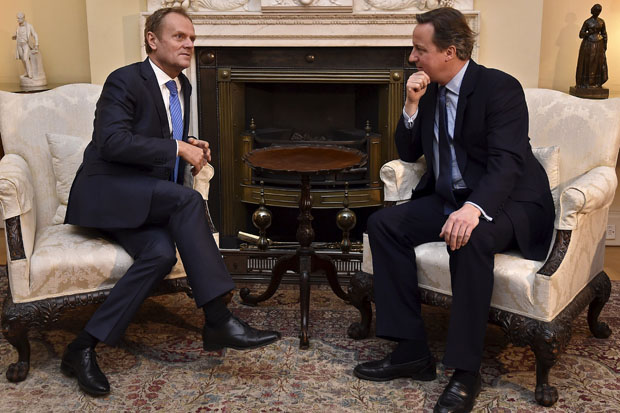

Last week Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, tabled proposals which the government hopes will form the basis of the UK’s renegotiated relationship with the European Union. Politically, the proposals may be just the job: a new commitment to enhance competitiveness, proposals to limit benefits to migrants, recognition that member states’ different aspirations for further integration must be respected, and creation of a ‘red card’ mechanism to block EU legislation. Legally, however, they raise more questions than they answer.

This ought to have been an opportunity to look at the Court of Justice of the European Union, whose reach has extended to a point where the status quo is untenable. Aside from eroding national sovereignty (which it does) the current situation also undermines legal certainty — which, in turn, undermines good governance. Proper reform needs to address the EU legal order, in particular the jurisdictional muscle-flexing of the Court of Justice in Luxembourg. The new proposals do not do this. Instead, they duck the issue entirely — clearing the way for a whole new body of EU rights law.

The problem lies in the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which was solemnly proclaimed in 2000. It described 50 new ‘rights, freedoms and principles’ in addition to the 20-odd rights in the European Convention of Human Rights. So the Charter was a far more sweeping document. In 2007 it was given legal force by the Lisbon Treaty. At the time, it was loudly proclaimed that this would change nothing: that it just underlined what was anyway the case. Smelling a rat, the Labour government asked for — and was given — an assurance in writing that Britain would not be affected by the Charter. It was called ‘Protocol 30’.

Before the ink had dried on Protocol 30, concerns were voiced about its precise meaning and effect. Tony Blair assured the Commons that there was nothing to worry about: ‘It is absolutely clear that we have an opt-out from both the Charter and judicial and home affairs.’ David Miliband, then Foreign Secretary, also assured us that the Charter would not ‘extend the reach of European courts into British law’. Four years later, the coalition government was giving similar assurances: in March 2011 Ken Clarke, then Justice Secretary, said that the Charter was of more presentational importance and did ‘not actually change anything’.

In English courts, however, another picture has been emerging. Take the case of ‘NS’, an Afghan asylum seeker who arrived in the UK seven years ago. Given that he had come via Greece, where he had been arrested, the UK sought to return him there under the Dublin Convention. But he argued that the treatment of asylum seekers in Greece amounted to ‘degrading’ treatment, contrary to Article 3 of the European Convention of Human Rights. He also sought to invoke the Charter of Fundamental Rights — which, according to Messrs Blair, Miliband and Clarke, should have been legally impossible.

This was referred to the Court of Justice in Luxembourg which ruled (in effect, and after some domestic backsliding) that the British opt-out had no legal force and the Charter of Fundamental Rights applied in the UK in precisely the same way as in any other member state. Since then, the English courts have increasingly been urged to recognise and give effect to new Charter-based rights in areas of law as diverse as employment disputes, immigration and asylum claims.

So where are we now? Mr Justice Mostyn has put it well. In 1998, the Human Rights Act incorporated large parts of the European Convention on Human Rights — but not all of it. Some parts were deliberately missed out by Parliament. Yet the Charter, he said, ‘contains all of those missing parts — and a great deal more’. In spite of Blair’s endeavours, he said, ‘it would seem that the much wider Charter of Rights is now part of our domestic law’. Moreover, he said, it ‘would remain part of our domestic law even if the Human Rights Act were repealed’.

Which raises an interesting question. The Tusk proposals suggest that the government does not intend to use this ‘renegotiation’ to reassert any form of Charter opt-out or control over its scope. So why repeal the Human Rights Act while the Charter, with its far wider panoply of rights, remains?

As David Anderson QC and Dr Cian Murphy have argued, the Charter — as it now stands — requires ‘enormous faith to be placed in the Court of Justice, its ultimate arbiter’. My current view is that a court which has been known in cases of vital importance to ignore its own rulings (viz, the infamous Digital Rights Ireland case), and give no reasoned explanation for doing so, is acting capriciously rather than judiciously. It does not inspire much faith.

Now, when Britain is debating its relationship to the EU, we should state our position afresh. Here is an opportunity to restore a measure of constitutional coherence. Let us not pass it by.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Marina Wheeler is a human rights lawyer practising at One Crown Office Row. She was called to the bar in 1987 and took silk last month. A longer version of this article can be found on ukhumanrightsblog.com. Marina Wheeler is a human rights lawyer practising at One Crown Office Row. She was called to the bar in 1987 and took silk last month.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in