Born in New South Wales in 1888, George Finch climbed Mount Canobolas as a boy, unleashing, in the thin air, a lifelong passion. When he was 14, the family emigrated to Europe. There, as a young man, Finch excelled both as an alpinist and a student, enrolling at the prestigious Zurich Federal Institute of Technology, where he won a gold medal which he subsequently melted down to buy ropes and belays. He was six feet two, with broad shoulders and blue eyes, and he played the piano beautifully.

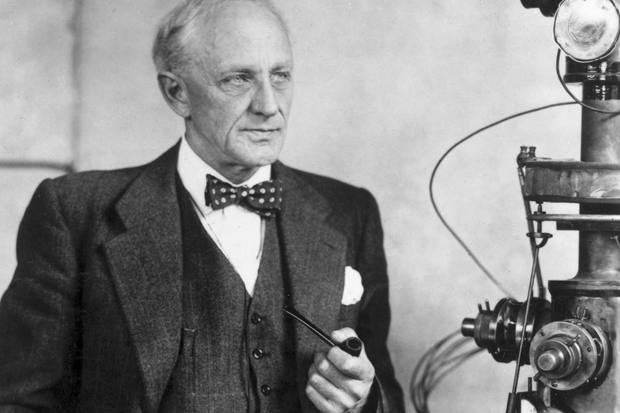

In 1912 he moved to London to work as a research chemist, joining the Fuel and Refractory Fuels team at Imperial College the following year. From the outset, he upset convention in the climbing fraternity. His independent spirit proved almost disastrous when he progressed to the higher peaks of the Himalaya, a region then in the grip of the saurians of the Royal Geographical Society in Britain, and its rival the Alpine Club.

Finch failed a medical for the first official British expedition to Everest under suspicious circumstances, but he went on the second, in 1922, and with Geoffrey Bruce climbed to 27,000 feet — higher than anyone before. When he got down to the lower Camp III, he ate four fried quail truffled in foie gras. Polarised views on the use of oxygen dominated the enterprise. Finch was one of the main supporters of oxygen use, and brilliantly pioneered new equipment, but many thought it was cheating — just as a decade before they had sniffed at Amundsen reaching the South Pole with dogs. Finch wrote in the Royal Geographical Journal that by guzzling from a canister

the climber does not smooth away the rough rocks of the mountain or still the storm; nor is he an Aladdin who, by a rub on a magic ring, is wafted by invisible agents to his goal.

The journalist Robert Wainwright has conjured up the rasp of crampons on sheet ice, the taste of peaches eaten from the tin, and the bitchiness endemic among the frozen-bearded tribe of climbers and explorers — a characteristic still thriving. Finch wrote in his diary of ‘a legacy of hate’. The organisers passed him over for the third Everest expedition, in 1924. George Mallory went, as he had on the previous two. (‘You know he doesn’t like me,’ Finch had written home.) This time, Mallory didn’t come back.

Wainwright acknowledges that Finch was abrasive. He was, according to a peer, ‘overbearing and a difficult climbing companion’. One tent-mate wrote irritably of his tendency to tell tall stories, adding, ‘Cleans his teeth on 1 February and has a bath on the same day if the water is very hot, otherwise puts it off till the next year.’ But Wainwright also reckons, I am sure correctly, that when it came to the establishment, the usual class prejudice was at work: Finch was simply not the right sort.

Meanwhile, two marriages had slid into a crevasse. The first had yielded two sons, but Finch believed they were not his, as he was serving with the Royal Field Artillery at the time, most significantly as a chemist in the ordnance division (little is known of what he actually did in the war, though he got an MBE for service in Salonika). Wainwright thinks Finch was right about the adultery. The eldest son was shipped around the world to stay with various relatives who didn’t want him, eventually fetching up in Hollywood, where he won a posthumous Oscar. His name was Peter Finch. A happy third marriage produced three daughters.

Finch continued to work as a researcher, contributing to breakthroughs in, for example, the efficiency of iron as a catalyst. According to Wainwright, he was fortunate to begin his career ‘at a watershed moment, when the untapped mysteries of science met the industrial demands of a new century’. During the second world war he did brilliant work to limit fire damage.

Wainwright has researched thoroughly, deploying important primary sources as well as Finch’s memoir. Few will wish this book longer, especially in the pages on climbing technicalities (‘It was here that the piton was invaluable’). Stylistically, one observes a weakness for cliché — cats escaping from bags, folk living in the lap of luxury and so on — and, worse, an occasional lack of clarity. ‘Often,’ the readers learns, ‘it is a quirk of fate that sometimes creates an opportunity.’ Make your mind up, man: does this happen often, or sometimes?

In the end Wainwright evokes admiration for his subject, but little sympathy. The Maverick Mountaineer fills in gaps about a key player in the golden age of the slopes, and as such it is a welcome addition to the shelves, even without an index. The book is also a threnody for a vanished era of both science and climbing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in