It’s widely agreed that the most difficult form of opera to bring off is operetta, whether of the Austro-German or the French tradition — interesting that the Italians wisely eschew the genre (so far as I know), while the British stay with G&S and their inviolable traditions, including the audience’s laughing in all the right places. In the past four days I have been to two performances of French operetta, neither of them much of a success, for quite different reasons.

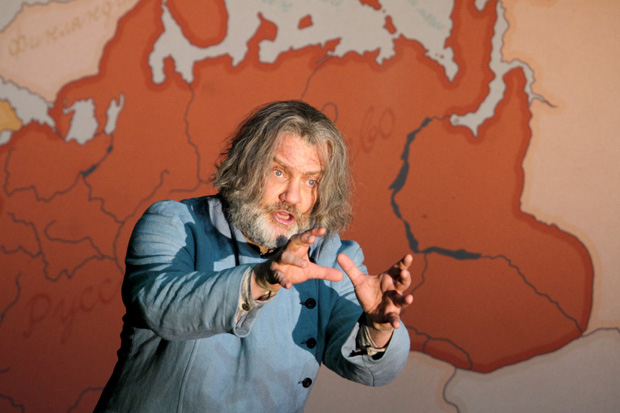

Opera Danube is a young company devoted to nurturing singers who recently graduated from one or another of the many music schools. It works with the Orpheus Sinfonia, a small orchestra of players at the same stage of their careers. Its artistic director Andrew Dickinson reminds us in the programme that times are hard, even harder than usual, for young musicians. When I think of the innumerable fine singers I have seen in productions at the RCM, RAM and the Guildhall School, and how many of them have never been heard again, I can only feel amazement that anyone even tries. However, Opera Danube does itself no favours by regarding St John’s Smith Square as its spiritual home (Dickinson’s words). It is a deep and lofty building, in which speech turns into mere incomprehensible echo, so that the narration and dialogue in Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld got lost. The production was semi-staged, with, so far as I could tell, decent singers who in a different, more intimate acoustic might have made more of an impression. They might usefully be taught the first rule of operetta, indeed of all comedy: PLAY IT STRAIGHT. The narrator, who doubled as Jupiter, and trebled as the director, was Simon Butteriss, an immensely experienced singer, writer and actor in opera, musicals and recitals. His polished performance gave, I’m sure without intention, the impression of someone bent on upstaging everyone else in the cast, and wasn’t helped by being so camp that it seemed to belong to a different kind of entertainment. Still, it goes without saying that this work is a masterpiece, especially its brief last act, where the performance finally gave an indication of what this company might achieve.

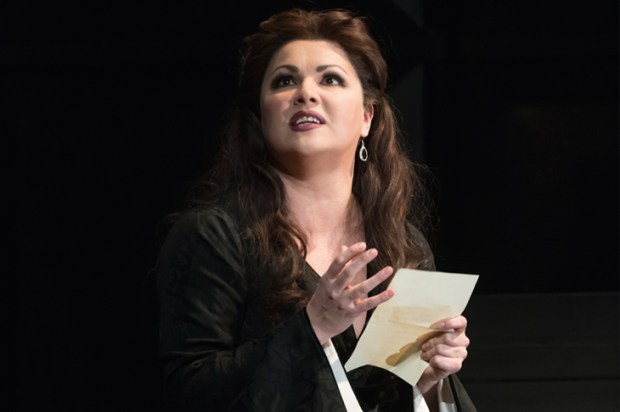

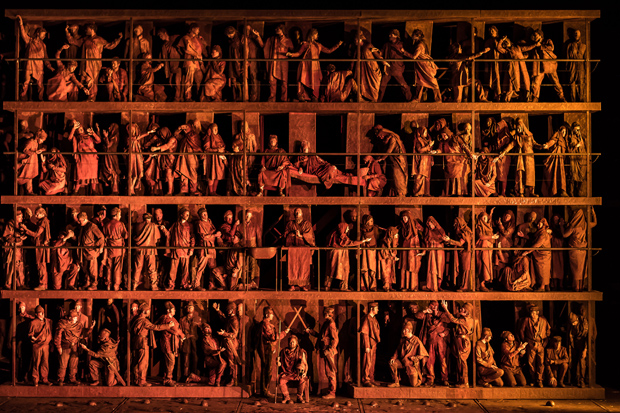

It does not go without saying that Chabrier’s L’Étoile is a masterpiece, and unfortunately the production at the Royal Opera, its first there, is not likely to win it many converts. For one thing, the size of the theatre is quite inappropriate for this intimate work, the scoring of which has many of the felicities that one expects from this composer, but which don’t make their mark, even when played with such care and lucidity as Mark Elder achieved. For once the main attraction of the evening was the ever-mobile and enchanting scenery, two-dimensional but cute and sometimes witty. But one should be on the alert when it is felt to be necessary to have such visual busyness, accommodating singers in Near Eastern costumes, and most of them, I’m relieved to say, not hamming it up.

This opera definitively refutes the view that with adequate music the plot can be as silly, confused and unfollowable as it likes. You can’t have characters in whom you take any kind of interest without there being a context for their behaviour, including the music they sing. The plot of L’Étoile is impossible to follow — I read four summaries of it, each of them quite different, but all equally inane. Another danger signal is that the characters sport such names as Tapioca, Siroco, King Ouf, and Hérisson de Porc-Épic. We are in the world of Gallic facetiousness, which it seems, surprisingly, Chabrier failed to recognise as being as wearisome as it is. He loved many kinds of mischief and comedy, was a purveyor of them often in brilliant music, but without any taste in libretti. It was interesting to note that the Royal Opera’s audience laughed conscientiously as often as it could until the interval, but then for the longer second half went quiet, hoping that L’Etoile would accumulate a momentum that simply isn’t there. The only enjoyment, for me, was in the lovely performance by Kate Lindsey of Lazuli, a trouser role that she carried through with exquisite poise and taste, singing arias of a semi-seriousness that carry more conviction than the naughty sprightliness of much of the score. A pedlar who ends up as Ouf’s chosen successor, Lazuli largely sidesteps the tiresome main action. Ouf, the sadistic king who celebrates his name day by executing a citizen who has spoken ill of him, has rather little to sing, and Christophe Mortagne’s performance didn’t make one regret that, being painfully short of top notes. There are two imported characters in this production, an archetypal Englishman and Frenchman, Dupont and Smith, who enact clichés about their respective countries. They added, I’m afraid, to the effect of laboriousness which made this short opera seem like a grim foretaste of eternity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in