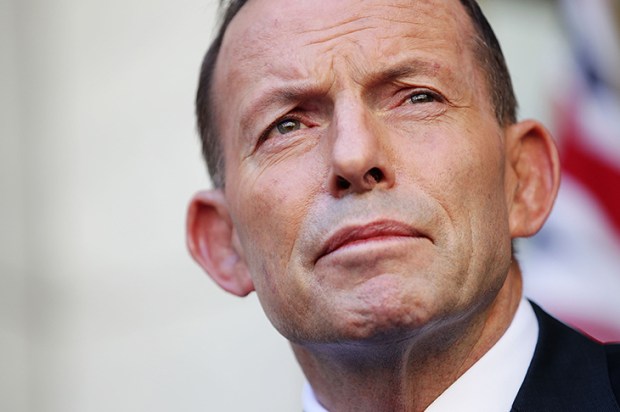

Tony Abbott’s Quadrant essay on his government, previewed in the Weekend Australian, reveals a Tony we can greatly regret is no longer prime minister: a thoughtful policy thinker and a clear intellectual and philosophical contrast with his urbane assassin, Malcolm Turnbull. A Tony with an economic and national security vision appealing to mainstream Australians.

Abbott asserts ‘I’m confident we could have won the 2016 election with a programme of budget savings and lower tax’. On that surely he’s right. Over the full three-year term, with the annus horribilis of 2015 behind him, and an opportunistic populist in Bill Shorten leading an arrogant Labor party learning nothing and forgetting nothing from its savage self-destruction under Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, Abbott was highly likely to win the only poll that counts.

There’s a compelling case for the Abbott government being remembered positively, and Abbott makes it. Among other achievements he cites the abolition of the carbon tax; his government’s early decisions not to bail out mendicant businesses like Holden and SPC Ardmona; pursuing the Heydon royal commission into union corruption; reversing the slide on national job creation and, making a start on the huge task of budget repair dumped in his lap by Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard.

Above all, Abbott claims – and deserves – credit for pursuing extensive budget repair against implacable resistance. ‘This was achieved despite a hysterical opposition, a populist Senate crossbench, a poisonous media – and, as shown by the very well-organised September 2015 spill, some senior members who didn’t want the Abbott government to succeed’, he writes. He especially acknowledges the impact of the 2014 budget’s toxic reception on his leadership and his government’s popularity.

But his Quadrant essay also gives us unintended glimpses of another Tony: the mortal politician who didn’t get the politics of staying in office right. What frustrates about Abbott’s account is that, in explaining the challenges he faced and why they needed dealing with, it was only written after the leadership horse had bolted. That Turnbull is turning out a disappointment in terms of a lack of clear plans, direction and vision – a naughty boy rather than a Messiah – is small comfort to the millions of Australians who embraced Abbott, his conservative values and his belief that lower taxation and greater private sector productivity are the keys to overall economic prosperity.

Team Abbott’s collective shortcomings, and stubbornly refusing to correct them despite the wake-up call of February 2015’s leadership spill motion, let Turnbull through the door last September. That let down those wanting purposeful, conservative government, and find themselves left with Malcolm ‘what do I do now?’ Turnbull.

Abbott does hint at some misjudgments. He acknowledges that while the most controversial 2014 budget measures, the GP co-payment and university fee deregulation, did not breach pre-election undertakings they did make his ‘no surprises’ pledge look hollow. He ‘perhaps’ regretted his government not having a mini-budget on coming to office ‘to avoid a pre-Christmas hit on business confidence’, nor making more use of its comprehensive Commission of Audit report to make a compelling case for difficult fiscal medicine in that crucial 2014 budget.

What’s airbrushed out is Team Abbott’s systemical dysfunctionality: Joe Hockey was found out very quickly as a poor Treasurer yet collective pride and stubbornness kept him in post; charismatic and domineering chief-of-staff Peta Credlin isolated Abbott from his own MPs and simply became too powerful in her own right (a leading organiser of Turnbull’s strike told me sufficient Liberal MPs effectively voted against him just to remove her); damaging ‘captain’s call’s’, most notably knighting Prince Philip; and the menagerie of the Senate crossbench was not well handled.

But the Abbott government’s political foundations were wrong from the start. Had Abbott gone to the 2013 election as Jeff Kennett did in Victoria in 1992 – effectively promising painful decisions and savings must be made to fix Labor’s omnishambles, and Abbott was the Churchillian leader willing and courageous enough to make them – what happened in 2014 would have been more readily, if reluctantly, accepted by an electorate sick of Labor’s profligacy and in-fighting. Instead, the Coalition, with decisive victory in its grasp, bent over backwards to reassure voters they weren’t nasty bastards.

Similarly, poor policy work made Abbott’s budget repair mission almost impossible. For example, 2014’s GP co-payment plan, for which I was the canary in the government’s pre-budget media coal mine, was atrociously designed in terms of its unanticipated reach into pathology and radiology, and its inexplicably diverting Medicare rebate savings into a massive medical research fund. It was too clever by half: failure to both consult and anticipate fevered political attacks on the policy meant the government’s very sound message about fair, modest and affordable Medicare price signals was utterly lost from the outset.

Sadly, Abbott’s achievements in destroying two Labor prime ministers, and setting about the unenviable task of cleaning up Labor’s wreckage, were devalued by his brutal removal. He has to write a positive account of his prime ministership, because no-one else is anytime soon.

As Abbott writes, the strength of his policy legacy – on border protection, budget repair, the environment and national security – is demonstrated by Turnbull not only accepting but embracing it. The salesman has changed, but not the products. Abbott’s key prescriptions were right then, and right now.

Abbott was more sinned against than sinning. His tragedy is that despite his personal strengths of character and loyalty, backbench despair with his dysfunctional inner circle finally gave Turnbull opportunity to strike. Had he been given more time, even one week, he could have restructured his ministry and office, but enough of his colleagues lost their nerve, however fleetingly. If only Tony Abbott had written something like this essay in March 2013, what he and his then impending government stood for would have been far clearer, his political task as prime minister far simpler, and he’d probably still be in the job. If only

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Terry Barnes is a former advisor to Tony Abbott

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in