The Royal Opera has bitten the bullet so far as Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov goes, and opted to stage the original 1869 version, with no modifications or additions from his revised 1874 edition, which used to be called ‘definitive’ but which seems to be under a cloud nowadays. Rimsky-Korsakov’s version has been pushed right to the back of the doghouse, so that it might soon be revived for its historical interest. Before I launch into my praise of the new production, which is an unqualified triumph, I would like to register some reservations about the work itself, in any of its versions.

It’s routinely said that the hero of the opera is not Boris but the Russian people, tormented and downtrodden as they have always been and still are. As portrayed unflinchingly by Musorgsky and his source Pushkin, they are credulous of the latest rumours, especially nasty ones, quick to change sides, prone to bullying the less well-abled, in fact very much what crowds are, but hardly qualified to be called heroic. That is no doubt an accurate view of them, and it does what Musorgsky surely wanted to do, and that is to show the human condition as hopeless, cheerless, interesting only insofar as we have an appetite for misery.

Boris himself is not to any degree heroic: our first glimpse of him is as unwilling to become Tsar, and his opening address to the people is so downbeat that it’s amazing that they celebrate his coronation so exuberantly — this is marvellously done in this new production, the chorus electrifying and bells pealing out seemingly throughout the theatre. In the synopsis provided in the programme, after the account of the celebrations, we get in italics (meaning that this part of the story is not included in the opera), ‘Years pass. Boris proves to be a good and wise ruler. Under his rule Russia prospers for some years.’ But there is no depiction of this. The next time we see Boris, after his coronation, he is in the family circle but in low spirits, since Russia is undergoing a slump. He turns out to be a sympathetic family man, proud of his son’s knowledge of geography, but as soon as he becomes meditative, in his great monologue ‘I have attained the highest power’, anguish and guilt set in, and he is easily persuaded by the oily Shuisky to hallucinate the past, and that is all we see of him, until he asks the Holy Fool to pray for him, and then follows the death scene, again very low-key in the original version.

I really can see no reason for keeping to this austere text, when, without diffusing interest, the 1874 revision contains so much marvellous music. Talking with the Stravinskys and Robert Craft in 1966, W.H. Auden proposed the category of the anti-opera opera, and Boris is certainly a leading candidate, along with From the House of the Dead and (Auden proposed) Pelléas et Mélisande. It has none of the winning qualities that opera-lovers love, and is rather a test of devotion to the grim unvarnished truth than to any kind of allure.

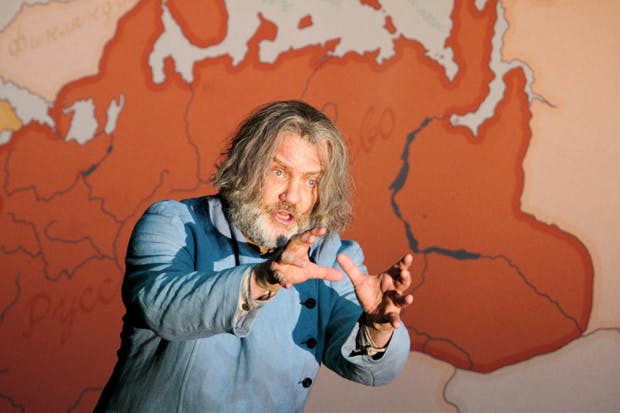

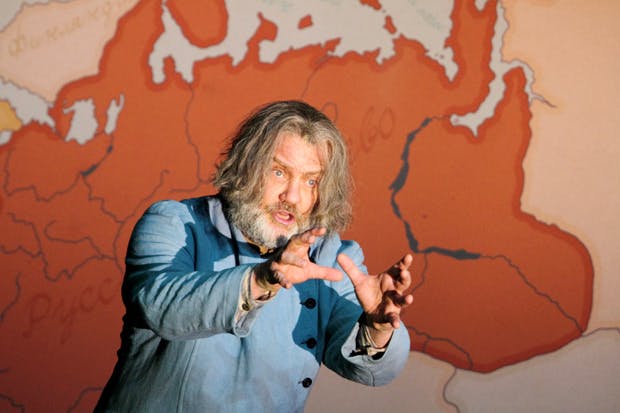

Bryn Terfel, singing his first Boris, is heroic to the extent that he makes Boris as colourless and uncharismatic a character as possible. I’m sure this is intentional, and a tribute to his extraordinary artistic integrity. Lacking the blackness of the great Borises of the past, above all Boris Christoff and Nikolai Ghiaurov in living memory, his softer-grained voice expresses shades of torment and uncertainty that make him a less commanding but more moving figure than we might expect. The whole cast displays a fanatical selflessness, with the exception of John Tomlinson, himself a Boris of distinction, who here hams it up gloriously as the drunken monk Varlaam. John Graham-Hall repeats his gruesome Shuisky from ENO’s similarly grim production of 2008, though he has now taken his wheedling so far that he sounds as if he is singing Mime in Siegfried. Pimen, the encyclopaedic monk, is skilfully taken by Ain Anger, and the Pretender, who hardly registers in this version, is David Butt Philip, a good singer but looking like an ingenuous boy scout.

The whole thing is brilliantly timed and executed by Antonio Pappano, one of his finest achievements at the Royal Opera. Richard Jones produces a two-layered affair, upstairs a tireless re-enaction of Dmitry’s murder — the programme states, ‘We advise that it is not suitable for children under the age of 12 years’ (does the writer of that ever watch TV?) — while below every scene but one is drained of colour, an assault of drabness. But every dramatic point is registered to the full, and the work was received with what seemed like awe.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in