When Tom Birkin, hero of J.L. Carr’s novel A Month in the Country, wakes from sleeping in the sun, it is to a vision: the vicar’s wife Alice Keach in a wide-brimmed straw hat, a rose tucked into the ribbon. ‘Her neck was uncovered to the bosom and, immediately, I was reminded of Botticelli — not his Venus — the Primavera. It was partly her wonderfully oval face and partly the easy way she stood. I’d seen enough paintings to know beauty when I saw it and, in this out of the way place, here it was before me.’

So universally recognised are Sandro Botticelli’s two most famous paintings, we can immediately picture the vicar’s lovely wife: mild, tempera features, loose, fair hair, a Yorkshire ‘Primavera’ as much a part of the North Riding landscape as Ribston Pippin apple blossom or oxeye daisies.

The instant familiarity of Botticelli’s two Renaissance belles is the starting point for the V&A’s Botticelli Reimagined. The exhibition opens, not with the ‘Venus’ or ‘Primavera’ proper (the Uffizi, understandably, does not lend them), but with a video clip of Honey Ryder rising from the waves in her white bikini in Dr No. Sean Connery’s James Bond gawps, as Botticelli’s sponsor Lorenzo de’ Medici must have done in his day.

It’s an oddly back-to-front exhibition. We begin with the art of the past few decades, move on to the rediscovery of Botticelli in the 19th century, and end in 15th-century Florence with the artist and his workshop. Co-curator Ana Debenedetti explains that the intention was to begin with the two most famous images and ‘peel back the layers of history’ to show how Botticelli has been made and remade. The Vogue 100 show at the National Portrait Gallery also suffers by this topsy-turvy conceit, starting in 2016 and working its way back to 1916. It is counterintuitive and maddening to the visitor.

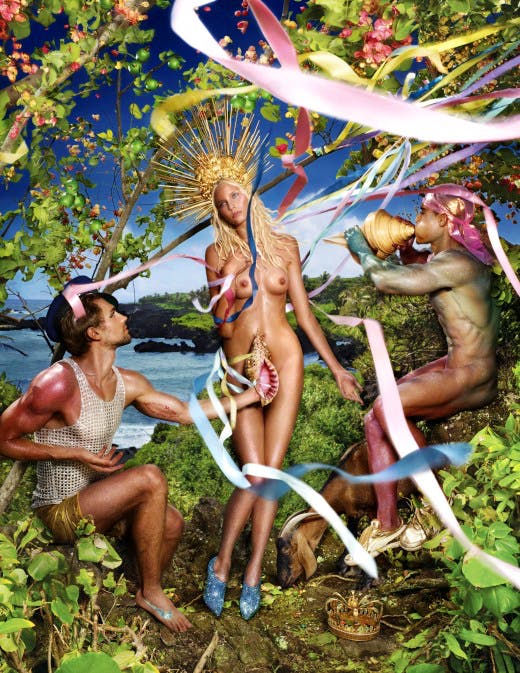

Rebirth of Venus (2009) by David LaChapelle

The first room gives us ‘Botticelli as Brand’. This is a jumble: a Lady Gaga album cover, a Dolce & Gabbana trouser suit, Andy Warhol. Each reuses scraps of the ‘Primavera’ and ‘Venus’. The photographer David LaChapelle gives us Venus as Barbie, blonde and waxed, and Joel-Peter Witkin Venus as a hermaphrodite.

You are grateful to leave all that behind for the 19th century’s take on Botticelli. William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and Evelyn De Morgan may have done watered-down Botticelli, but at least they understood something of line, modesty, beauty, leggiadrìa — the Renaissance ideal of lightness, suppleness, grace.

Coming into the last room, then, is like the shade and cool of a loggia after the clamour of the piazza. Here is Botticelli’s Simonetta Vespucci as if cut from ivory, her golden hair plaited and threaded with pearls and ribbons. Here is his personification of Autumn in black and red chalk, womanly and swelling, skirts dancing behind her. And here is Pallas, twisting her fingers through the hair of a centaur, her bodice coiled with laurels. The Uffizi has been good enough to lend her, and she is a treat.

Pallas and the Centaur (c.1482) by Sandro Botticelli

At the Courtauld Gallery, Botticelli and Treasures from the Hamilton Collection reminds us that Botticelli did more than classical dream girls. Between c.1480–95 Botticelli undertook the illustrations to an illuminated manuscript of Dante’s Divine Comedy. There are 30 of them here — ten each from the ‘Inferno’, ‘Purgatory’ and ‘Paradise’ — lent by the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett.

How thrilling it is to find Botticelli loosed from loveliness. His Lucifer is a wild, ill-mannered brute, stuffing Cassius and Brutus feet first into two of three mouths. Judas, legs flailing, has already been eaten up to his waist. This Lucifer has satyr’s horns, a warthog’s tusks and toenails as long and curving as a toucan’s beak.

Illustration by Sandro Botticelli to accompany Canto XXXIV of ‘Inferno’ from Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’

In heaving visions of the circles of hell, damned souls gnaw scalps and bite haunches, wrestle, squabble, squall and squat in despair. One sinner carries his own severed head before him like Perseus with the head of Medusa. Because this is Botticelli, the bodies are taut and Olympian. They all have hair like Samson. There is pathos in seeing once magnificent men bent and tortured.

Beatrice, when she appears in Paradise, is suitably beatific. A head taller than Dante, her neck is a column of marble, her hair swept by celestial breezes. She is unmistakably Botticelli — a sister to Venus and Primavera.

Illustration by Sandro Botticelli to accompany Canto VI of ‘Paradiso’ from Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’

The desperate pretenders in the first room of the V&A only ape Botticelli. They imitate his contours, repeat half-covered breasts and the tilt of a head for their copy-cat goddesses. But they miss the elusive spirit of Beatrice and Pallas, Autumn and Simonetta, Venus and Primavera, their ease and divine grace.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in