A few weeks ago, I looked out on the Cathedral of Monreale from the platform on which once stood the throne of William II, King of Sicily. From there nearly two acres of richly coloured mosaics were visible, glittering with gold. In the apse behind was the majestic figure of Christ Pantocrator — that is, almighty. The walls of the aisles and nave were lined with scenes from the Bible. In another panel, just above, Christ himself crowned King William.

It was a prospect of the greatest opulence and sophistication stretching in every direction from this regal vantage point. The mosaics are in the manner of Byzantium, and probably executed by Greek artists, but the architectural plan and inlaid floors are derived from medieval Italy. This then, Padre Nicola Gaglio, the priest who was escorting us pointed out, was a building in which the Christian traditions of East and West, Rome and Constantinople, were combined and contrasted.

That’s true. But what is extraordinary is that that list does not by any means exhaust the interaction of civilisations that took place in 12th-century Sicily, soon to be explored in an exhibition at the British Museum. For a century after the conquest of the island by Norman forces in the 11th century, Sicilian society deserved the contemporary term multicultural.

The island was also quadrilingual, as an inscribed stone from 12th-century Palermo demonstrates. This inscription recorded the transfer of the remains of one Anna, mother of a priest called Grisandus, to a private chapel. It does so, however, in Latin, Greek, Arabic and Judaeo-Arabic (an Arabic dialect written in Hebrew characters for an Arabic-speaking Jewish population). Each text is slightly different, since — for example — the stone is dated 1149, according to western Christian chronology, 6657 according to the Byzantines, who began at the creation of the world, and 544 by Islamic reckoning.

Norman Sicily even had an English connection. At Monreale, on the wall beneath the colossal figure of Christ — his right hand alone, according to John Julius Norwich, is six feet high — is the unexpected figure of St Thomas Becket of Canterbury. Perhaps Becket’s image was put there among other sainted bishops in an apologetic spirit, since St Thomas had been hacked to death at the instigation of William II’s father-in-law, Henry II of England. Becket’s murder took place in 1170, or at most two decades before the mosaics were created.

There was an intimate connection between Norman Sicily and Norman England, both of which had been conquered by Viking-descended soldiers from northern France. The rulers of Norman Sicily had begun as mercenaries and freebooters, the sons of a minor noble called Tancred de Hauteville. The youngest of these, Roger, ended up as Count of Sicily; while his older brother, Robert Guiscard, ruled much of southern Italy. Their Italian wars took place at much the same time as William the Conqueror’s invasion of England.

The first Norman incursion into Sicily was in 1061, though the process of subduing the entire territory took decades. Before the Norse buccaneers arrived, Sicily had been under Islamic rule for more than a century; most of the population at that point was probably Muslim. Until the Islamic invasion, the island had been part of the Byzantine empire and culturally Greek.

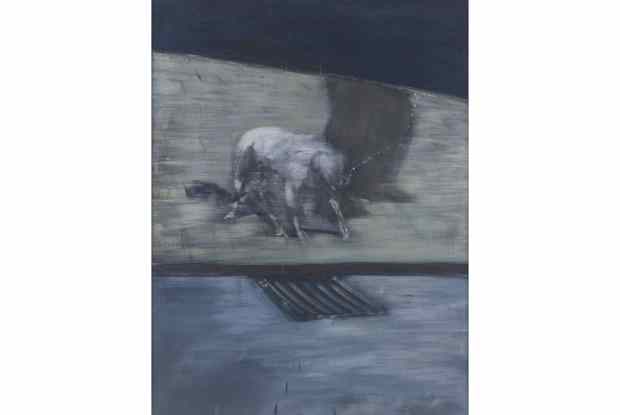

Norman Sicily was therefore a jigsaw of cultures. Its full complexity is made clear inside the Cappella Palatina of the Royal Palace in Palermo, which I visited the following day in company with Dirk Booms, one of the British Museum curators. There the walls are covered with superb Byzantine mosaics, floors made by Italian master craftsmen, perhaps from Salerno. The most startling feature, however, is the wooden ceiling of the nave, a complex masterpiece of carpentry with starburst patterns and the honeycomb forms known as muqarnas (see p29), the whole of which is covered in Arabic inscriptions and figurative paintings in the style of contemporary Egypt. Some of these represent the king who commissioned the work, Roger II (1095–1154), son of the original conqueror, seated cross-legged in the manner of an Islamic ruler.

By the time his chapel was inaugurated in 1143, Roger controlled Sicily, most of Italy south of Rome, and large areas of North Africa. In some respects he and his successors followed the ways of the Middle East. They maintained harems and built superb pleasure palaces around Palermo, enthusiastically compared by Ibn Jubayr, a poet and traveller from Andalusia, to ‘necklaces strung around the throats of voluptuous girls’. Some of these, including those known as La Cuba and La Zisa — from al-Aziz (‘the Magnificent’) — closely resemble similar structures in 12th-century Algeria and Egypt.

The difference is that, miraculously, the Sicilian buildings still exist. Nowhere else, in fact, does so much of the magnificence of an early medieval monarch survive. The Palace of the Normans in Palermo contains 12th-century interiors, including the ‘Room of Roger’, which has mosaics of regal leopards, peacocks and centaurs in a landscape of date palms and orange trees. In the royal gardens around the city there roamed a Romanesque menagerie, including ostriches, panthers, lions, apes, bears, giraffes and elephants.

The Norman kings of Sicily were among the greatest rulers of their day. Roger II clearly thought himself the equal of the Emperor in Constantinople. Under his reign Sicily, making full use of its pivotal position in the centre of the Mediterranean, was powerful and prosperous as it had seldom been before — and never has been since. His hybrid Greek-Latin-Islamic state was hugely successful. Islamic bureaucrats kept records in flowing Arabic, the bishops were Italian, French and English, and the Syrian Christian Arabic and Greek-speaking George of Antioch functioned as ammiratus ammiratorum, emir of emirs, or commander-in-chief.

However, there was a catch, as Dirk Booms explained as we stood in front of the wonderful church in Palermo built by George of Antioch. ‘Sicily was a place of tolerance, but it was not a place of integration — except at court.’ The various populations — Greek, Latin, Muslim, Jewish — lived in separate districts of Palermo. Under Roger II’s son, William I, this patchwork society began to disintegrate. In 1161, there was a rebellion. The chief minister, George of Antioch’s successor, Maio of Bari, was assassinated, the king himself was imprisoned, and there were attacks on the Muslim population, who fled into the mountains.

‘When the power of the king fell away,’ Dirk Booms concluded, ‘it was clear that there were underlying tensions.’ After William II died without an heir in 1189, Norman Sicily, after lasting for a glorious century or so, quickly fragmented. Perhaps its lesson is that a multicultural society can be remarkably successful economically and culturally, but without true integration it is vulnerably fragile.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Sicily: Culture and Conquest is at the British Museum from 21 April to 14 August.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in