Whimsy, satire and deadpan humour: welcome to the world of Andrey Kurkov. If you know Kurkov’s work, The Bickford Fuse will be no surprise and need no introduction. It’s not Death and the Penguin or A Matter of Death and Life (read them first), but it’s certainly Kurkov in welcome and familiar mode. For newcomers and to summarise: he’s really a kind of Ukrainian Kurt Vonnegut, a serious writer never more serious than when he’s being funny about unfunny things, and with a whole lifetime of unfunny things to be serious about. As the second world war was to Vonnegut, so the Soviet Union is to Kurkov. If — as Oscar Wilde believed — our duty towards history is to rewrite it, then Kurkov has long been working overtime. If you want to read about the Soviet Union but can’t face reading, say, Robert Service, and you have a penchant for the strange and surreal, you could do worse than reading Kurkov.

The events in the book (published in 2009 in Russian) begin at the end of what Russians call the Great Patriotic War: it’s a book, according to Kurkov himself, about ‘Soviet man’. A group of disparate Soviet men go wandering throughout the land in search of meaning — and that’s it. This perhaps makes the book sound like Tarkovsky’s Stalker — one of those seemingly endless allegories of life under communism. It is in fact more like an allegory of life under any -ism: maddening, subject to chaos and chance, and often unintelligible.

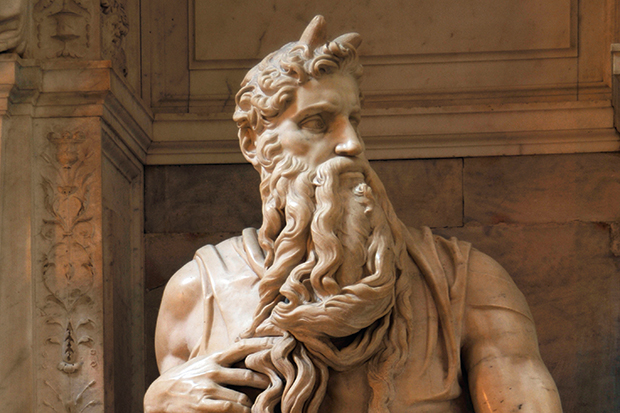

There is Gorych, for example, and his unnamed companion, driving around with a massive searchlight in the back of a truck. There is the mysterious occupant of a black airship, prone to throwing overboard cases of cigarettes. There is Andrey, who leaves the remote monastery where he lives with his father and brothers, having laboured with them to make a wooden ‘humming’ bell. And Kharitonov, who is carrying with him the Bickford Fuse. The fuse is clearly a symbol, though of what it’s not entirely clear. All Kharitonov knows is that ‘as long as he’s searching for someone to give it to or for something to do with it, his journey has a goal, and, hence, some meaning’.

In his introduction to the book Kurkov explains that it ‘remains the dearest and most important of all my works’. As he explains:

There are nations with great, complex histories, nations that have seen much blood and many tragedies, nations that are so hopelessly bound by their histories that they cannot move forward into the future, or even into a normal ‘present’.

This seems to be the key to Kurkov’s process and the presentation of his material: everything is arresting, but nothing seems quite to add up.

When I was at school we all had to read Alexander Solzhenitsyn. In the foreword to my ancient dog-eared copy of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, now 30 years overdue from the library at Ongar Comp, the poet Aleksandr Tvardovsky writes, ‘The effect of this novel, which is so unusual for its honesty and harrowing truth, is to unburden our minds of things thus far unspoken, but which had to be said.’ I have two children currently studying for their GCSEs in English: as part of their course work they are required to compare and contrast the spoken language of Jamie Oliver and Gordon Ramsay. Honestly. Seriously. Let them read Kurkov.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £12.49. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in