Jesuits, the leading apologists for Rome and Catholic revival in Elizabethan England, cast a long shadow over the paranoid post-Armada years. For one thing, they set much store by Romish ‘persuasion’ (sophistical reasoning) and were often superb linguists. Among the languages codified by Jesuits were Guaraní in Paraguay and Sri Lankan Tamil. Jesuit attempts to translate the Bible into local vernaculars were often less successful, however. Japanese converts to Jesuitism apparently still believe that Noah survived the flood in a canoe; scribal error had corrupted the Ark into an unlikely means of salvation.

Inevitably, translation is a frayed and ragged version of the original (Traduttore traditore, the Italians say: ‘The translator is a traitor’), but the Bible presents a special challenge. Not one word in the Old Testament is believed by Jews and Gentiles to be unintended or extraneous, so there is little room for error. The King James Bible of 1611 of course remains a marvel of cadenced tautness and high-flown poetry, but that was an exception.

In his scholarly and entertaining account of biblical inerrancy down the ages, Harry Freedman makes much of the so-called ‘Wicked’ or ‘Adulterous’ English language version of 1631, which neglected to include the word ‘not’ in the seventh commandment. Amid the familiar exhortations ‘thou shalt not kill’ and ‘thou shalt not steale’ was the clamorous slip up ‘thou shalt commit adultery’. The edition was hastily withdrawn on the orders of a horrified Charles I.

Others have gone so far as to tinker with holy writ. The gay-friendly Queen James Bible, published in New York in 2012, rephrased or simply removed perceived anti-homosexual passages on the grounds that James I was himself, in the words of the anonymous editors, ‘a well known bisexual’. This is a queer kind of logic, but there is always a special risk, says Freedman, in tampering with the gist of God’s word. The 1998 Complete Jewish Bible intruded words in Yiddish slang, when Yiddish wasn’t even a ‘twinkle in the eye’ of first-century Jewish Christians. The intention (a perfectly laudable one) was to demonstrate the Jewish provenance of the New Testament. The disciples are warned, hip-jive style, not to schmoose on the road, while in John x 19–20 the Judeans say of Jesus: ‘He’s meshugga! Why do you listen to him?’ The American comedian-crooner Lord Buckley (now sadly forgotten) had burlesqued Jesus of Nazareth in a similar way: ‘Here come the Nazz, cool as anyone you ever see, right across the water — walkin’!’ But that was a stand-up routine, not the Holy Bible.

Freedman (who has a PhD in the language spoken by Jesus and his followers, Aramaic) is at pains to point out the Hebraic roots of the New Testament. Matthew’s gospel, the most demonstrably ‘Jewish’ of the four, seeks to show how every recorded act of Jesus is rooted in Jewish scripture. The first Christians, a messianic Jewish sect, adhered to circumcision and Mosaic law, and were known to outsiders as Nazarenes. (Even today, the word for ‘Christian’ in Arabic is Nasrani.) Christianity did not detach from Judaism definitively until 70 AD, when Roman legions under Emperor Titus destroyed the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

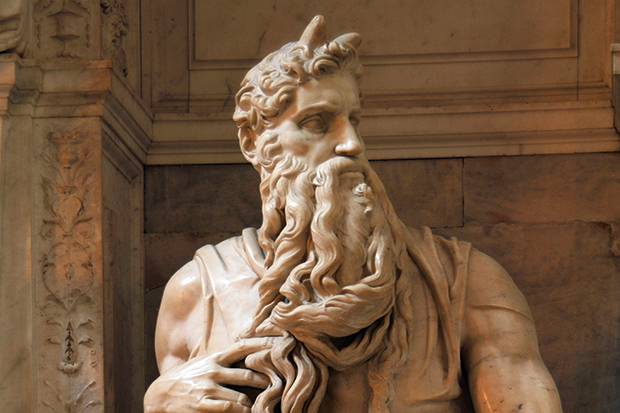

For Jews, of course, the Bible is only the Old Testament, but even then the designation Old Testament is ‘inappropriate’, says Freedman, as it implies that the Hebrew Bible has been superseded. Perhaps that is the point. Illuminated Anglo-Saxon translations of the Bible (of which the Lindisfarne manuscript is the oldest to have survived) sometimes encouraged anti-Semitism. An Old English version of the Old Testament, for example, mistranslated Moses’s face as gehyrned, or ‘horned’. In the medieval mind it followed that all Jews had devilish horns. (Michelangelo’s 1513 statue of Moses is one of the most famous of such depictions.)

As the Reformation spread across northern Europe, so the translated Bible became a useful weapon of protest against the licentiousness and unbridled greed (as it was seen) of the Vatican, with its lubricious friars and other purple embarrassments. William Tyndale’s early-16th-century translation of the Bible did for English what Luther had done for German: it loaded and vivified our language with coinages that we still use (‘my brother’s keeper’, ‘pour out one’s heart’, ‘signs of the times’). Daringly, Tyndale translated the Greek ekklesia as ‘congregation’ rather than ‘church’. Congregational singing — an innovation of the Reformation — allowed the faithful to become participants in church worship rather than remain as mute spectators.

Freedman’s history, a breezy affair from start to finish (‘Luther was a shrewd operator’), is the beginning of wisdom in all things scripturally buckled, deformed and misshaped. If only we had a Lord Buckley version. ‘The Nazz. That was the cat’s name. A carpenter-kitty.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17.00. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in