There is fakery in the air. And maybe the French are done with deconstruction. A drone operated by a French archaeology consultant called Iconem has been languidly circling Palmyra, feeding back data about the rubble with a view to reconstructing the ruins and giving the finger to Daesh. Cocteau said he lies to tell the truth. Iconem flies to tell the truth.

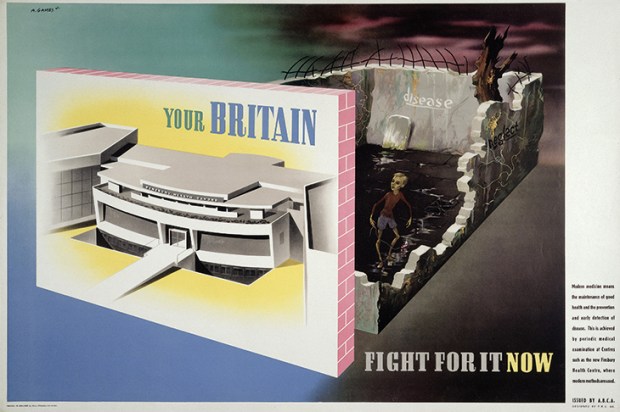

In April, an exhibition called The Missing: Rebuilding the Past opened in New York which examined ‘creative means to protest preventable loss’. It was timed to coincide with the temporary erection of a frankly underwhelming two thirds-scale replica of the Palmyra Arch in Trafalgar Square, London. It goes to Times Square, New York, in September.

And opening today at the Venice Biennale is the V&A’s A World of Fragile Parts (until 27 November), which looks at how new technologies of scanning and additive manufacturing can help preserve — or give new life to — buildings and artefacts threatened or destroyed by environmental decay, the depredations of tourism or the nihilistic vandalism of fundamentalist whack-jobs.

They say that in our post-postmodern condition, nothing is new and everything is just a version of something else. And the V&A certainly has form in this quizzical arena: its stupendous 19th-century Cast Courts are a masterclass in cultural appropriation, imperial patronage and shameless repro. But when Victorian adventurers built wooden shuttering, poured plaster of Paris around Santiago’s Portico della Gloria and shipped the result back to Kensington, they did not ask the questions about purpose and authenticity we need to ask today.

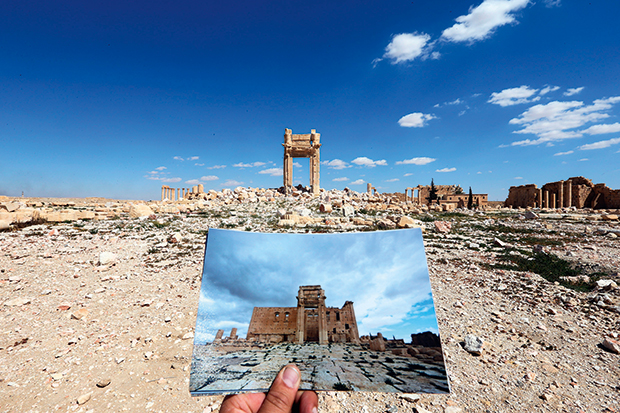

There is a distinction between fake, copy and forgery, although sometimes that distinction is blurred, especially so with advanced technology. Certainly, advanced reproductive techniques have made real the theoretical musings of Walter Benjamin’s famous essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’. Here, Benjamin wondered what actually constituted the value of a ‘work of art’. Was it a design that could be indefinitely and inexpensively reproduced, or was it something mystical that resided in the unique materials and surface effects of the original? Which is to say, is the beauty of the Palmyra Arch rooted in pitiably broken site-specific desert rubble, or can it be reproduced by data-driven robots in Italy and sent to London, New York and on to Dubai?

The enormous reproductive ability of industry has made ideas of copying central to art and design culture. The copy might not be a deviant variant, but the essential thing. What is mass-production if not the copying of an original design? The architect Philip Johnson said that he liked minimalism because it was ‘easy to copy’. Then there is Warhol with his knowing and clever exploitation of commercial print processes. And (Elaine) Sturtevant with her knowing and clever exploitation of Warhol himself.

Sturtevant, who insisted on her surname alone, as if she were a branded product, began copying Warhol in 1965. Getting in on the joke, Warhol even gave her one of his original silkscreen flatbed stencils to work with. And when asked how he made his pictures, Warhol said, ‘Ask Sturtevant.’ Meanwhile, Richard Prince began copying other people’s photographs in 1975. Thirty years later, at Christie’s in New York, his ‘Untitled Cowboy’ became the first photograph to sell for more than $1 million. Assumptions about authorship were violently disrupted.

Then there is the artist J.S.G. Boggs, who liked to make meticulous drawings of $100 bills and present them as payment in restaurants, further monetising his art by demanding change. Quite correctly, Boggs pointed out that ‘real’ money is itself a source of mystification since, in terms of liquidity, most banks are fraudulent. The authorities tolerated Boggs’s pranks until he switched his reproduction technique from drawing to a colour laser printer and the Philadelphia police busted him, although one’s bound to say that there is snobbery in this distinction. Old-fashioned drawing made Boggs an artist, newfangled lasers made him a counterfeiter.

Beneath all of this is an idea about authenticity, perhaps the most fugitive of notions. Nicky Haslam, who once dyed his pubic hair purple, quite correctly says, ‘The very idea of authenticity is a sham.’ Our responses are layered: copies aim to reproduce, but fakes aim to deceive. But sometimes, copies are superior to the original: Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who helped craft our understanding of the neoclassical — the ‘neo’ is important here — declared the Apollo Belvedere to be the ‘highest ideal of art’. And maybe he was correct, although he was also a little deceived: the statue Winckelmann admired was a Roman copy in marble of what had been a Greek bronze original. We can call it a re-edition.

The expert eye can often be fooled. In 1896, amid much clamour, the Louvre acquired the Tiara of Saitaphernes, a 3rd-century bc Scythian notable. It was soon found to be the work of one Israel Rouchomovsky of Odessa, a chancer who became a celebrity. But another faker, Hans van Meegeren, went to jail for his atrocious Vermeers. We look at van Meegeren’s ‘Christ at Emmaus’ today and are boggled by the fact that the credible art historian Abraham Bredius could write about the hideous picture, a gaudy travesty of the still and quiet Vermeer, so enthusiastically in the Burlington Magazine of 1937.

This was because Bredius was experiencing that phenomenon of taste being influenced by the cognitive part of the brain: he was told the painting was a Vermeer, so he adapted his judgments accordingly. The same phenomenon affects the wine trade where, at the top end, fakery is rife. Modern technology means labels can easily be reproduced: it’s not a culture that is policed. Thus, Sotheby’s wine expert Serena Sutcliffe estimated that perhaps 20 per cent of major private wine collections were fake bottles: if you have paid Pétrus prices for what’s in fact an Australian alcoholic fruit bomb, the cognitive parts of your brain will certainly be inclined to point your thinking in a certain direction.

Recent legislation means that designs of furniture and such are protected by a similar sort of copyright to that which protects literature. There will be no more unlicensed ‘Bauhaus’ chairs nor any Charles Eames knock-offs, although this is at odds with the original democratic design mentality. Whatever; the Chinese are beyond the reach of the law. You can buy a car called a Hongda, and Land Rover is concerned that if it reveals its new Defender too soon, copies will be available in China before exports begin from Solihull. And a fake Goldman Sachs was recently discovered in a Chinese province.

In the 19th century, the French Académie des Beaux-Arts thought copying was the second most important artistic discipline after life-drawing. It said nothing of ‘creativity’, which then counted for little. In American museums, there’s now a debate about how far restoration of modern paintings should go. The colour has bled from your Rothko: do you take it back to the original, falsifying the facts, or enjoy its state of contemporary decay?

Viollet-le-Duc’s architectural restorations (including Notre-Dame) were powered by his imagination. He did not seek to restore an original, but to use it as a starting point for an imaginative fantasy about the Middle Ages. Similarly, Thorvaldsen’s overenthusiastic ‘restoration’ of the Aegina marbles in the 1820s approached the condition of forgery. They were de-restored in the 1960s. If you’re looking for ‘truth’, the history of art is not a good place to start.

When it comes to the Palmyra Arch — what exactly are we restoring? There is no single, fixed, constant version of the past. It is always being rediscovered and that rediscovery is a creative adventure at least as speculative as dreams about the future. And often as wrong-headed.

Of course, every sentient being deplores the brainless destruction of the picturesque ruins described by the Comte de Volney and adored by Rose Macaulay, but patient restoration of Palmyra is as futile as correctly remembering an evaporating dream. Certainly, it’s gratifying to nullify the destructive work of Daesh’s explosives with drones and 3D printing and complex resins, but why confront the ugly lie of Islamic State with a tacky fake? There’s a nobility in ruins that technically perfect copies can never rediscover. Palmyra is a universal idea, not an archaeological site in the Syrian desert. The deplorable new ruins add to Palmyra’s meaning, a message written in the sand.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in