Woolworth’s spectacles. Pudding-basin haircut, rather sparse. Norfolk jacket. Pyjama cuffs below trouser legs and sleeves. Paints and brushes in an old black perambulator. And a sign propped up on a gravestone: ‘As he is anxious to complete his painting of the churchyard Mr Stanley Spencer would be grateful if visitors would kindly avoid distracting his attention from the work.’

This was Spencer in his Cookham dotage, a picture of wilful eccentricity, painting the church, cottages, meadows and Thames banks he had known since childhood. An odd little fellow, with the emphasis on little. He was 5ft 2in, by his family’s estimation, and better suited to the ambulance service than he was to the infantry when he volunteered in 1915. He was no taller than 5ft, said his brother-in-law. He was but 4ft 10in said his patron, Sir Edward Beddington-Behrens, remembering Spencer on a painting trip to the Swiss Alps, jolted and bumped up a mountain on the back of a mule. Spencer is smaller with every telling and made more ridiculous, more like an absurd, endearing pet, the more he shrinks.

He sketched the warships at Port Glasgow on an unspooling loo roll. He was partial to biscuits and bully-beef. His favourite meal was buttered white bread with strawberry jam. How delightfully strange, how deliciously English. Sir Stanley Spencer of the commuter-belt resurrections.

His Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere, painted with scenes from his years as a Bristol hospital orderly and Macedonia ambulanceman, is not five minutes from Highclere Castle, otherwise known as Downton Abbey. One can do Downton in the morning, a picnic lunch, then on to the Spencer Chapel with its well-drilled Tommies making their beds.

Recent exhibitions have given us Sunday-afternoon Stanley Spencer. He was hung in the Tate’s Art of the Garden show in 2004. Stanley Spencer: Painting Paradise at the Reading Museum opened in 2006 and Stanley Spencer and the English Garden at Compton Verney in 2011. Here was the Spencer of magnolias, greenhouses, allotments, wisteria, clipped yews and gardeners in plaited hats digging leeks. His flower paintings are popular choices for the covers of Virago Modern Classics.

We have, however, pruned Spencer back too vigorously. In our fondness for his roses, we have cut off his thorns. Something similar has happened to William Blake, mad as a March hare in life, but since recast as that nice Mr Blake, hymner of our green and pleasant land. Not the Blake who saw angels in the trees on Peckham Rye, who invented pantheons of priapic gods, who sat naked in the summerhouse of his Lambeth garden playing Adam to his wife’s Eve.

As Blake has become the go-to mystic for primary-school poetry recitals — ‘Tyger Tyger, burning bright’— so Spencer has become a National Trust national treasure. Here is your Stanley Spencer scone: will you have him with clotted cream or jam?

But in this, the 125th anniversary of his birth on 30 June 1891, it is right to think again about Spencer, to see beyond wisteria blossom. A volume of Spencer’s letters and jottings, Stanley Spencer: Looking to Heaven, published by the Unicorn Press, and three exhibitions offer the opportunity to do so. These are Stanley Spencer: Of Angels and Dirt at the Hepworth, Wakefield (until 5 October); Stanley Spencer: A Panorama of Life, at the Jerwood Gallery, Hastings (15 October until 8 January 2017); and Stanley Spencer: Visionary Painter of the Natural World (a gardener’s dream of bluebells and magnolias) at the Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham (until 31 October).

Spencer sulked and rebelled against wheedling letters from his agent Dudley Tooth asking if the artist mightn’t like to paint a few more of ‘those little flower pictures that people have always liked so much’. If he hadn’t had a first wife, Hilda, to support and two daughters, Shirin and Unity (the original occupiers of the black pram), and a second wife Patricia, who wouldn’t sleep with him, lived with her own girlfriend Dorothy Hepworth, and was, according to Shirin, ‘after Daddy’s cash’, he would have painted only biblical religious scenes and not contemptible, but saleable, rock gardens and riverside picnic tables. He mocked his punter-friendly paintings as ‘my Ascot fashions, my sweet-pea colours’.

His true inclinations were weirder than that. His human figures from the earliest days at the Maidenhead Technical Institute and the Slade School of Fine Art in London (where he was called ‘Cookham’ for his provincial, mummy’s-boy routine of going home each evening) are unsettling: helium-balloon heads, kapok-doll bodies, badly stuffed, waxy faces held too close to candles. One of his earliest commissions, ‘The Fairy on the Water-lily Leaf’ (1909), an illustration to a fairy tale, was rejected by the author because the fairy was ‘too hefty’. Indeed she is a large girl and must have seemed the more so to eyes accustomed to the corseted waifs of Arthur Rackham.

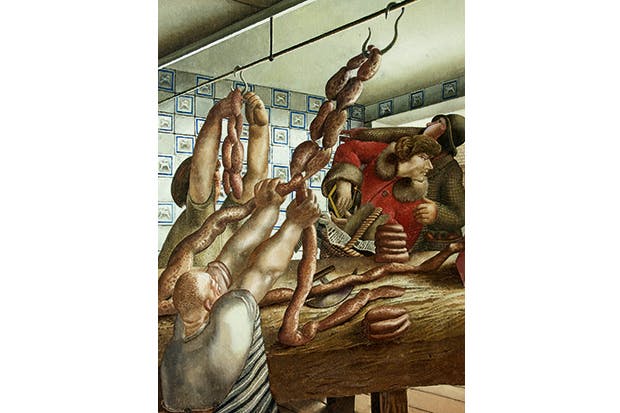

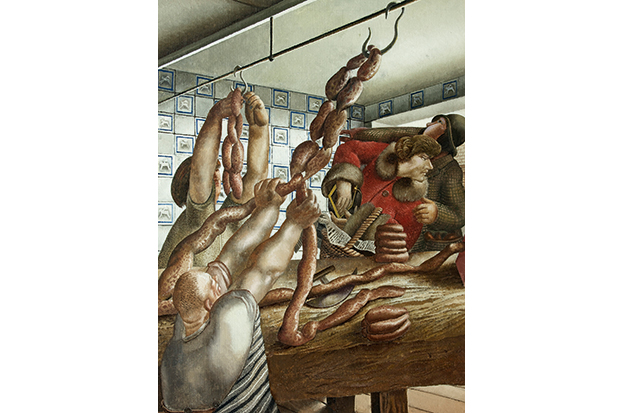

Later Spencer works, among them a bulging, bearded ‘St Francis and the Birds’ (1935), were rejected by the Royal Academy, while his free-loving, shirt-tearing, thigh-groping erotic paintings were censured by the director of public prosecutions. His viewpoints are often those of the peeping Tom: oblique angles, chinks in fences, from a window on an upstairs landing. The perspective is often distorted, the artist at one remove.

As a 26-year-old in Macedonia in 1918, he wrote home to his sister Florence (she was ‘Dear Flongy dear’; he was ‘Stan’): ‘Rather like these Greek churches; they have that sort of owlish creepy feeling about them.’ The phrase is right for Spencer’s own art; at any rate the art he liked to paint, the Christs in the wilderness and frostbitten soldiers, not the dahlias and pea sticks. This side of his art is not grotesque, not horrible, but it is owlish and creepy. ‘I am on the side,’ he said, ‘of angels and dirt.’

The Hepworth Wakefield, which takes this for its exhibition title, will do much to restore Spencer, to show us the Spencer of angels and dirt, holy visions and dustbins, pendulous nudes and resurrections in churchyards as crowded as Tube platforms. ‘If that is Resurrection,’ said Winston Churchill on seeing the Tate’s ‘Resurrection, Cookham’ (1924–7), ‘then give me eternal sleep.’

Spencer’s fixation on this subject — the Hepworth show has five resurrections, and ‘The Resurrection of the Soldiers’ is the altarpiece climax of the Sandham Chapel cycle — came partly from his experience in Macedonia. ‘I had buried so many people and saw so many dead bodies,’ he recalled in 1927, ‘that I felt death could not be the end of everything.’

Spencer’s deeply weird ‘The Lovers (The Dustmen)’ (1934), included in the Hepworth show, is a cramped resurrection scene centred on a dustman cradled in the arms of a wife with a massive Giotto-like bell body. Other villagers hold up dustbin rummagings as holy offerings. ‘Nothing I love is rubbish,’ said Spencer, ‘and so I resurrect the teapot, and the empty jam tin, and the cabbage stalks, and as there is mystery in the Trinity, so there is in these three.’

Let us not have only summer-regatta Spencer, prize-rhododendron Spencer, cottage-garden Spencer. Let us have him in all his mystic strangeness: angels and dirt, jack-in-the-box tombs and Cookham High Street revelations, wilting cabbages and risen Christ kings.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in