Just as, in writing, many people use an exclamation mark to indicate that they have made a joke, so there is much to be said for dressing up in special clothes before making a humorous speech. The best man at a wedding does that, and so, once upon a time, did the MPs chosen to propose and second ‘an humble address’ to the monarch after the King’s or Queen’s Speech at the opening of Parliament. They wore court dress with ruffles and stockings.

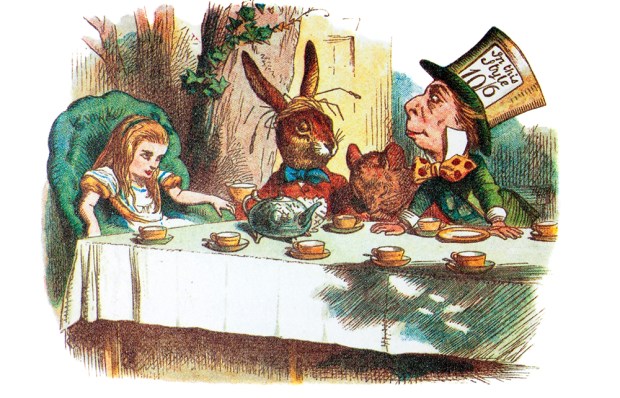

I’m not sure when this stopped. Someone will tell me. But it was in force when Frank Markham (who began as a Labour MP and ended as a knight of the shire sitting in the Conservative interest) seconded the motion in 1938. One of his ideas for a joke was to comment on American English. ‘I see,’ he told the House, ‘that in a recent American grammar that great phrase Sez you is now lifted to the dignity of “a doubtful affirmative”, while another phrase, Include me out, is defined as an “unqualified negative”.’ Perhaps soon, he suggested, they would label the Aye Lobby the Sez You Lobby and the other the Include Me Out Lobby. Ho, ho.

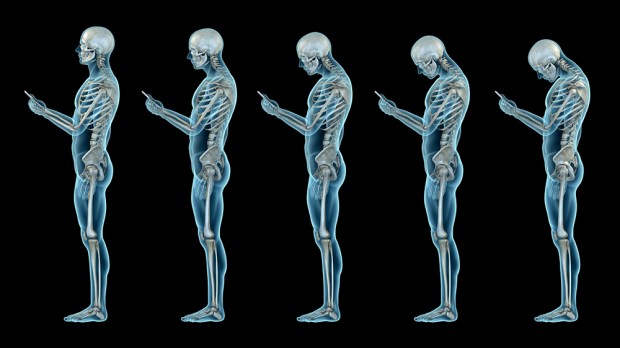

The phrase include me out is associated with the film producer Sam Goldwyn. But a common use of including gives me daily pain, however I’m dressed. Including should (by the laws of English) be followed by a noun or a noun phrase, for example: ‘true bugs, including aphids and scale insects’. What gives me pain is the use of including before a prepositional phrase (‘Look everywhere, including under the bed’) or an adverbial phrase (‘kinds of yeast, including for making bread’). I am not saying such uses are immoral. I’m just saying they aren’t English. It’s like moving a rook diagonally in chess.

Whether or not education ministers can distinguish parts of speech when ambushed on the radio, it is handy to have the terminology available to explain what is wrong grammatically with a construction that sounds wrong. Sounding wrong is a result of one’s inbuilt grammatical compass pointing out a deviation in one’s native tongue. To discover errors in a language learnt later requires explicit grammatical principles.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in