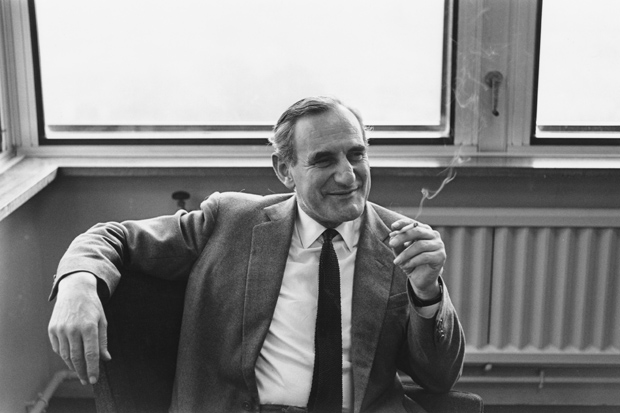

It is not easy to avoid clichés when writing about J.M.G. Le Clézio. Born in Nice in 1940, the recipient of the 2008 Nobel Prize for Literature is known in the Anglophone world as an ex-experimental novelist. His early work, exploring language and insanity, was praised by Michel Foucault. But since the 1970s his style has become more mainstream and his subjects — childhood, travel and landscape — more lyrical.

Reviewers quibble over the quality of translations, especially when there are two of the same novel in relatively quick succession. Le chercheur d’or (The Prospector) (1985), was translated into English by Carol Marks in 1993, and has now been retranslated by C. Dickson. Setting aside the question as to which of these competent and elegant translations is marginally better, it seems more interesting to consider why, more thanthree decades after it first appeared in France, The Prospector is a promising portal to the imagination of Le Clézio.

He claims that he wrote his first book aged seven, about the sea. He has also written a children’s story called Celui qui n’avait jamais vu la mer (The Boy Who Had Never Seen the Sea), published in France in 1978 and in the New Yorker the year of his Nobel win. The Prospector opens with homage to the sea:

As far back as I can remember, the sound of the sea has been in my ears. Mingled with that of the wind in the needles of the she-oaks, the wind that never stops, even when you leave the coast behind and cross the cane fields, it’s the sound of my childhood.

Dickson’s translation captures the hypnotic ebb and flow of Le Clézio’s prose. Readers must find their sea legs and become accustomed to a semi-regular swaying about between tenses: ‘It’s as if everything I’m feeling, everything I’m seeing now is eternal. I’m not aware that it will all soon disappear.’ Past, present and future tug at one another like crosscurrents.

The protagonist, Alexis L’Étang, lives an idyllic life in Boucan Embayment, on the island of Mauritius, when the novel opens in 1892. The Prospector is dedicated to Le Clézio’s grandfather, descended from François Alexis Le Clézio, who fled France in 1798 and settled with his wife and daughter in Mauritius before it turned from a French to a British colony. Although his early life has been one of privilege, Alexis already sees his home as a shipwreck. He is intuitively aware that his father’s fortunes are failing, even before the dream of building an electrical power plant on the island ends in bankruptcy and ruin. Then comes the year of the cyclone, which destroys everything Alexis has ever known:

The swollen sea invading the river inlets, drowning people in their cabins. Above all the wind that tossed everything upside down, that tore the roofs off houses, that snapped the smokestacks of sugar mills and demolished the hangars and destroyed half of Port Louis.

After the devastation, Alexis becomes obsessed with his father’s stories of the mysterious corsair who allegedly buried treasure on nearby Rodrigues island. As an adult, Alexis journeys back from France to Mauritius in search of the apocryphal treasure. The captain of the ship on which he is a paying passenger is sceptical:

‘I don’t believe that in this part of the world,’ he designates the horizon with a wide sweep of his arm, ‘there has been any other treasure than that which man has torn from the land and the sea at the cost of the lives of his fellow human beings.’

Instead of treasure, or gold, Alexis finds an alluringly independent female companion who teaches him to hunt for octopus and lies naked on the beach with him covered in sand:

Then we are inside one another. I’m not sure how. Her face is tilted backwards, I can hear her breathing, I can feel the beating of her heart and her warmth is within me, vast, more powerful than all of the burning days spent out at sea and in the valley.

He does not want to leave her, but does, for the trenches of the Somme in 1916.

Le Clézio evokes scenes of horror as brilliantly as scenes of beauty:

War doesn’t have anything to do with women, on the contrary, it’s the most sterile gathering of men that could exist… Every hour of every day the sounds of the dead filled our ears, the dull thud of shells exploding in the earth, the spurts of machine-gun fire and the strange rumour that immediately followed. Voice, the sound of men running in the mud, orders shouted by officers, the rout before the counter-attack.

Whether he is describing heaven or hell, Le Clézio lulls the reader into a hypnotic state, and the power of his prose reliably survives translation. His characters, lightly, almost mythically, sketched, often lie awake at night ‘eyes wide, listening to the rustling of the rain’, and so do his enthralled readers. It is not plot-spoiling to reveal that there is no actual treasure, only the exquisite prose Le Clézio has spun around his protagonist’s quest.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in