It was not so unusual for someone to turn into a god in Egypt. It happened to the Emperor Hadrian’s lover, a beautiful young man named Antinous, who was drowned in the Nile in the autumn of 130 AD. It was also the fate of Queen Arsinoë II, who had a complicated life. At the age of 15 she became wife to the 60-year-old ruler of Thrace. When he died in battle, she married her half-sibling, who murdered two of her sons. Her next husband was her full brother.

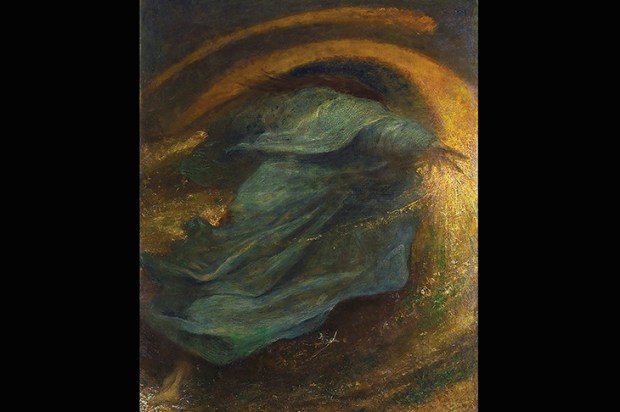

A headless sculpture of Arsinoë stands about halfway around Sunken cities at the British Museum. It is, as a label rightly points out, an almost perfect fusion of Greek and Egyptian art. Arsinoë was represented as an incarnation of Aphrodite. The hard black stone has been polished until it has the smoothness of skin; Arsinoë’s nakedness is emphasised by the diaphanous drapery that clings to her body.

This carving has the geometric structure of Egyptian sculpture, combined with the sensuous, living quality of the classical art we call Hellenistic. It is, in other words, a bit of a masterpiece, and also — like a good deal of art and behaviour associated with ancient Alexandria — distinctly weird.

Alexandria was one of the great centres of the Greco-Roman world, but a great deal less remains visible there than in Rome, Athens or Luxor and Cairo. In recent decades, however, some remnants — or, more precisely, remains of neighbouring and preceding settlements — are starting to emerge from beneath the waters of the bay of Aboukir, a few miles north-west of Alexandria itself.

Greeks began to settle on the Egyptian coast around the Nile Delta centuries before Alexander the Great founded the city to which he gave his own name in around331 BC. This was the place at which two civilisations met and mingled, though the Greeks seem to have been a great deal more interested in the Egyptians — whose culture was at this stage already three millennia old — than vice versa. Herodotus was fascinated by the place, even Homer mentioned the settlements at the mouth of the Nile.

These towns sank beneath the waves more than 1,200 years ago through a combination of rising sea level and subsiding land. The result is not perfect Pompeian-style preservation — the more humble structures, built of mud brick, would have dissolved more or less instantly. But a great many artefacts have survived, if in battered form, and there is probably a huge amount more still down there. Only 5 per cent of the site has been investigated so far.

A good deal of the drama of the exhibition comes from this recovery from the depths. The galleries are full of screens on which you can see underwater archaeologists at work, and objects such as gigantic statues and granite heads sticking out of the silt and sand. This presentation is atmospheric. Even if not many of the works are as fabulous as the sculpture of Arsinoë, they certainly have an impact — especially two red granite colossi representing a Greek king and his consort in traditional Egyptian guise, five metres high.

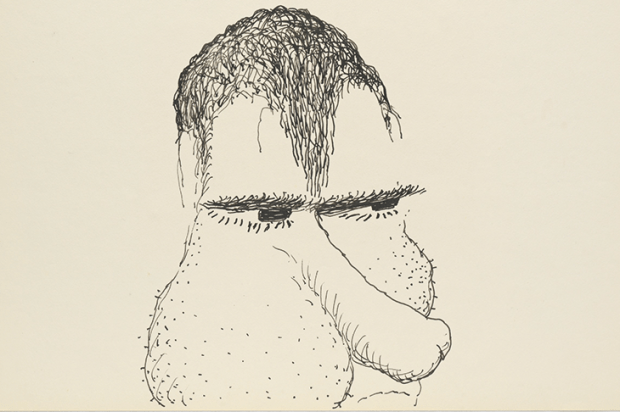

Such a merging of identities was characteristic of Alexandrian culture. Several deities, both Greek and Egyptian — including Osiris, Zeus and Dionysus — seem to have been combined into the major Alexandrian divinity, Serapis. A gigantic head of this slightly synthetic divinity, with luxuriantly curling beard and badly eroded nose, is one of the more spectacular pieces that have been raised from the sea, the top of a cult statue that would have stood almost as high as Michelangelo’s ‘David’.

The Nile Delta was a great place for the mixing and matching of religions. On the same disastrous trip on which Antinous died, Hadrian himself presented a magnificent, life-sized sculpture of the sacred bull Apis to the temple of Serapis, which is one of the star items in the exhibition.

Such objects make the Alexandrian Greek-Egyptian world seem closer and more real. Traditionally, it has tended to be seen as decadent. Thus more sober Romans felt that Mark Antony made a big mistake in falling for Cleopatra — a member of the same family as Arsinoë. On the other hand, Egyptian religions were exported to Italy. A sculpture of a priest of Osiris, clutching a sacred jar to his chest, was found in Aboukir Bay in a posture identical to that of a priest of Isis in a fresco from Herculaneum.

It’s a telling example of cultural fusion around the Mediterranean. Just such a movement of peoples from the south and north coasts of the sea is happening — in a shocking manner — right now. The migration crisis makes this exhibition seem oddly timely.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in