There is a moment at the start of most authors’ careers when it is hard to get anything published, and there is a moment towards the latter stage of some authors’ careers when it is hard to stop everything being published. A.S. Byatt is in the latter stage of her career, and however great the claims for her back (and future) catalogue may be, it hard to see why Peacock and Vine came to be here.

Byatt begins with an insight at the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice. Unfamiliar with the work of Mariano Fortuny, she describes something in the quality of the April light which brings to mind a very English green and thus William Morris. From this pleasant whimsy Byatt creates an essay that meanders through some connections between these men. These are not many.

Fortuny was born in Granada in 1871, 37 years after Morris’s birth in Walthamstow. Both men were innovators not only in design but associated realms. Morris’s founding of the Kelmscott Press and Fortuny’s innovations in lighting can be slightly compared. Both were interested in the Nordic myths — Fortuny through his admiration for Wagner, Morris very much not. At the entrance to the salon of the Palazzo Fortuny is a painting of the Valkyrie, Siegmund and Sieglinde. In Morris’s garden at Kelmscott is a topiary representation of Fafnir the dragon. Such facts do not quite an essay, let alone a book, make. By half way through this short work the author is wandering off into summaries of the work of various antiquarians and anthropologists with only very slight connections to either Fortuny or Morris.

Soon she slips into a pleasant meander among the byways of her subjects. Much is made of Proust and D’Annunzio’s mentions of Fortuny garments in their novels. But these are really no more than mentions, demonstrating the authors’ grasp of detail but hardly demonstrating any greater inspiration. Next we learn that ‘Reading Fortuny and Morris together made me think very hard, and with great pleasure’; and ‘I have made many discoveries during the writing of this essay’. Later, ‘I should like to know if Fortuny, when designing a gown, or a cope, or a velvet cape,

thought of the meaning of the images, or just of their traditional and satisfactory beauty.’

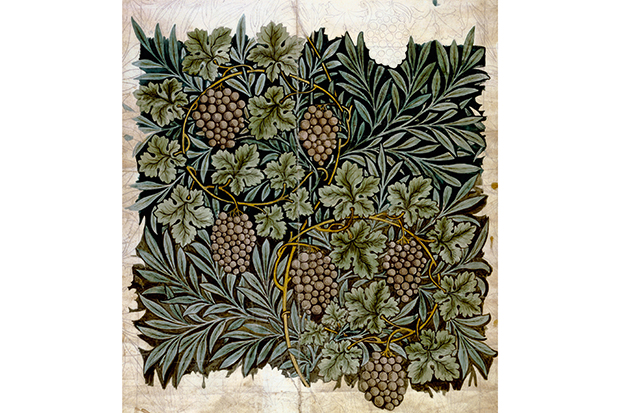

Designs for wallpaper with a vine pattern by Fortuny

Designs for wallpaper with a vine pattern by Fortuny

Finally, Byatt attempts to draw comparison between some of the imagery of her subjects. Using Fiona MacCarthy’s 1994 biography of William Morris and the lesser Fortuny bibliography in English, Byatt consider the prevalence of birds in both men’s designs. She also tries hard to decipher the presence of the pomegranate. Through the story of Proserpine, Byatt explains the iconography of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1868 painting of Morris’s wife (with whom Rossetti was having an affair) ‘The Blue Silk Dress’, where she holds the bitten fruit. And is that a pomegranate motif in that Fortuny design? There is a coat in the Museo Fortuny

of which I have only seen small black-and-white photographs. It is described as having a ‘pomegranate motif of Renaissance inspiration’. It is covered with bold pomegranate images… I’ve seen more than one of these photographs and the pomegranate is solidly there. It would be interesting to see it in motion.

This ‘project’ has — by Byatt’s own admission — given her great pleasure. Her publishers have done their best to share that pleasure about. They have certainly produced what is in these times an unusually lavish volume. Almost every other page has a photograph, and these are beautifully done. But they become as self-immortalising as the text. There is a photograph of Byatt sitting in the Palazzo Fortuny looking somewhat mystical. At the end is a photograph of the author’s hand poised over a notebook at the same place. Writing what?

Peacock and Vine is a publisher’s indulgence of an esteemed and estimable author. They may be right so to flatter her or they may be wrong. But in their desire to publish absolutely anything from Byatt, her agents and publishers might have missed a far larger prize. For although Byatt presents the link between her two subjects as a mystery that deserves unravelling, there is in fact no mystery. The link between the two artists is only that Byatt lives with Morris wallpaper and, abroad in Venice, saw something in the light that reminded her of home. The point an agent or editor ought to have made to her was that this moment of presumed insight in the aquamarine light of Venice was not cause for a thin book in search of tangential links between Fortuny and Morris, but the spark for a novel.

The post A trick of the light appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in