Grey men in grey overcoats walking through grey architecture. If you had to pick an image to reflect the current mood, the prevailing fashion in opera productions, this would be it. We may have outgrown the overtly Nazi settings of a few years back, but stepping into their highly polished boots are a whole platoon of non specifically fascist, 20th century exilic fantasies — all brutality, brutalism and barbed wire. Glyndebourne’s Poliuto, the Royal Opera’s Guillaume Tell, Idomeneo and Nabucco, even English National Opera’s Force of Destiny, the list goes on, and now boasts a new member in David Bösch’s Il trovatore.

At least Bösch isn’t going gentle into that all obliterating fascist night. Whimsy is a big part of this bright young director’s armoury, and his Royal Opera House debut is no exception. The chalkboard doodles, familiar to audiences of his Munich productions, are back, this time scrawling hearts and ‘Leonora loves Manrico’ everywhere, while Patrick Bannwart’s video projections temper the onstage tanks and guns with butterflies and snowflakes, doubling the lovers and their enemies with stick figures who live, love, die, and even commit infanticide, in uncomplicated two dimensions.

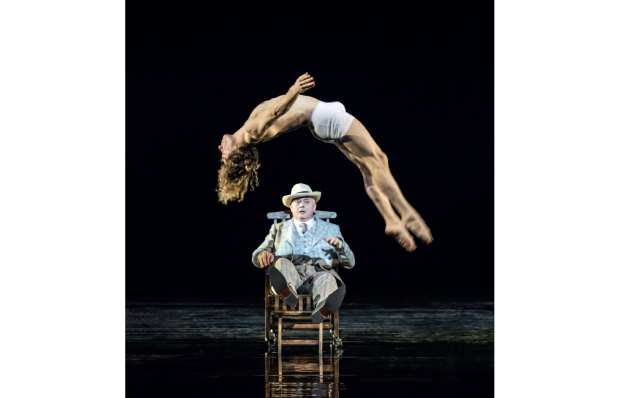

And that’s the problem. Either you take Verdi and Cammarano’s extraordinary plot of baby killing gypsies and long lost brothers seriously — a timely parable about the grotesque results of fear, prejudice and xenophobia — or you send it up. You can’t have both. To recast the gypsy Azucena and her son as members of an outlandish circus troupe— all bearded ladies and sequin clad acrobats — is to lose the essential humanity that both connects them to and divides them from di Luna and his court of paramilitary thugs. That so many scenes close with an act of violence, threatened but crucially unfulfilled, suggests that even the director himself recognises the dramatic incompatibility of his two genres.

And yet there are some deft touches here. The dolls that Ekaterina Semenchuk’s Azucena clutches speak of motherhood misplaced, of urges cruelly aborted; Leonora’s schoolgirl giddy passions are crucially imagined before they are experienced — a self fulfilling fantasy of escape rather than an adult romance. Perhaps with a more consistent cast this production might yet come into focus.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with Lianna Haroutounian’s Leonora, but there’s nothing particularly special either. It’s a voice lacking either outstanding beauty of tone or particular expressive skill, and she’s shown up both by the unexpected brilliance and weight of Francesco Meli’s Manrico (where was all that fire in I due Foscari, just a few seasons ago?) and, less forgivably, by Jette Parker Young Artist Jennifer Davis’s beautifully sung Ines. It doesn’t help that Gianandrea Noseda, making a belated company debut, seemed at odds with his principals for much of the evening, engaging in a protracted game of push me pull you over tempi that must have been even more unnerving from the stage than it was from the audience.

With Zeljko Lucic’s di Luna sounding uncharacteristically tired and drooping southwards in pitch, the only singer to emerge triumphant was Semenchuk. Chewing her way through Verdi’s dense writing, she found both the crunch of anguish and madness and moments of legato sweetness — musical hopes gloriously dashed in the horror of the final scene. But even she couldn’t quite ignite a show whose closing visual — a giant barbed wire heart that should have burst into flame but which, on opening night, failed fully to catch fire — rather says it all.

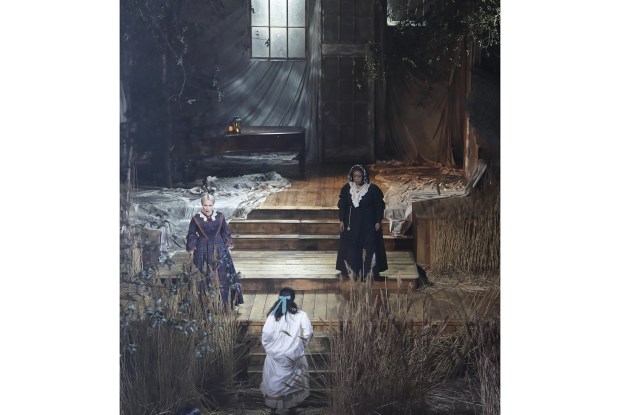

First seen in 2013, Daniele Abbado’s Nabucco is so dimly lit, so unremittingly grey in Alison Chitty’s designs, that it has become traditional to joke that you can’t even tell who are the oppressors and who the oppressed. But humour doesn’t sit well with a po faced production whose misty Stonehenge foreground and nervy computer game style video projections (cheaper than actually directing the chorus, one assumes) aspire to some weighty political message that remains frustratingly unclear.

But forget all that because this revival boasts something the Royal Opera hasn’t seen in a long while: Placido Domingo on vintage form. Where previous baritone excursions have only exposed the weakness of an aging tenor without the top notes, this Nabucco is something else, coloured with all Domingo’s old well oaked warmth and musicality of expression. His descent into madness is Lear like in scope, and set against the ferocious certainty and power of Liudmyla Monastyrska’s Abigaille — scorching at the top of the voice, with a pianissimo of outrageous daring — delivers a performance whose physical fragility only intensifies its charge.

Jamie Barton and stand in tenor Jean François Borras make a delicious pair of lovers, while the Royal Opera House chorus brings all its skill to shaping the famous Act 3 chorus. All are supported on the supple orchestral textures of Maurizio Benini, whose infinite shades of expressive grey are more welcome and infinitely more telling than those on stage.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in