Back in 1997 the New Yorker published a piece lampooning the proliferation of ‘Notes on the Type’ — those oleaginous mini-essays informing us that ‘this book was set in Backslap Grotesque Italic Semi-Detached, a variant of Bangalore Torpedo Moribund adapted in 1867 from a matrice by the Danish chiseller Espy Sans, a character if ever there was one’.

In the years since, the situation has gone from worrying to insufferable. Many non-fiction books now suffer from a severe case of distended colophon — sentence after rococo sentence, in the best M&S chocolate-box language, on the lineage of the type and typographer, on the amusing top notes of blueberry and persimmon that can be detected in the prose. I recently read one that explained not just who invented the font, but who was long thought to have invented it, before concluding: ‘The type is an excellent example of the influential and sturdy Dutch types that prevailed in England up to the time William Caslon developed his own incomparable designs from them.’ But if Caslon’s are incomparable, why not use them instead?

All this verbiage is meant to assure you of two things. The first is that the text is part of the great chain of ideas that stretches back through the ages. The colophon in my own recent book, set in the delightful Bembo, invokes Aldus Manutius, Francesco Griffo, Cardinal Bembo’s De Aetna and Claude Garamond’s Romain de l’Université. I doubt any of my readers could point out Claude Garamond in a line-up, let alone Aldus Manutius. But it gets the point across: people have been saying clever things in Bembo for centuries, and therefore anything written in Bembo is clever.

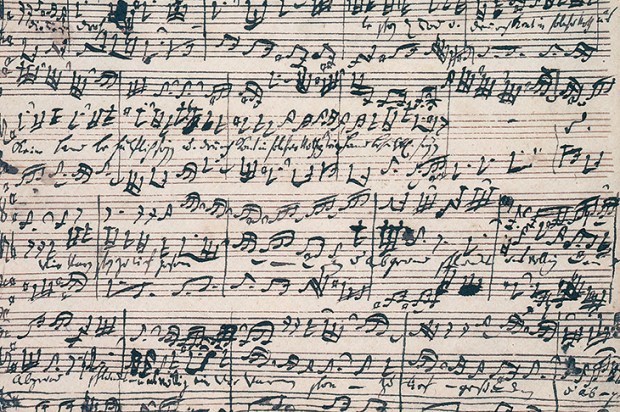

More importantly, as with organic coffee or single-origin chocolate, you’re being reassured that what you possess is a luxury good. Instead of thinking about Word documents and typesetting software, you’re meant to imagine a master typographer, running his fingers across the metal letters until he comes across the perfect fit: ‘Farage: My Story? Ah yes, the Baskerville, I think.’ It’s telling that the more digital society has become, the longer and fruitier the typography notes have got.

But here’s a strange thing. While these blurbs dwell endlessly on the provenance of a font, they never actually talk about the most important thing: what it looks like.

You don’t have to be a typography geek to appreciate the tiny differences in angle, weight and stroke, in the style of the ascending ‘t’ and descending ‘g’, that makes Caslon feel sturdier and Garamond airier — or how the sentence that feels stuffy in Trajan becomes frivolous in Comic Sans.

But when it comes to books, the job of a font (apart from being legible) is to be invisible. Its function is to tell you, almost subliminally, whether you are reading something by Primo Levi,Stephen King or Katie Price, and then get out of the way of the words.

When a book is a genuinely luxury object — the publishing equivalent of one of those gatefold-sleeved luxury albums with liner notes in the artist’s own blood — then yes, we might want to know about the font, and about the beautiful vellum-like paper, and all the other little details that reassure us that £50 was a small price to pay for such a status symbol.

Otherwise, rhapsodising about the font you’ve just read hundreds of pages of is like a magician boasting about how he did his tricks. It calls attention to the illusion — and in the process shatters it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in