In 1927, Georgia O’Keeffe announced that she would like her next exhibition to be ‘so magnificently vulgar that all the people who have liked what I have been doing would stop speaking to me’. Perhaps, then, she would approve of the massive retrospective of her work at Tate Modern. This show is, as is frequently the case in the largest suites of galleries on Bankside, considerably too big for its subject. The scale, however, is a matter of institutional overkill. Its vulgarity, magnificent or otherwise, is supplied by O’Keeffe (1887–1986) herself — in a pared-down, high-modernist way.

Resident for much of her long, long life in the New Mexican desert, she prided herself on her all-American toughness. ‘They make me seem like some strange unearthly sort of creature floating in the air,’ she complained in 1922 — ‘they’ being male critics and artists. The fact was, she continued, ‘I like beef steak — and like it rare at that.’

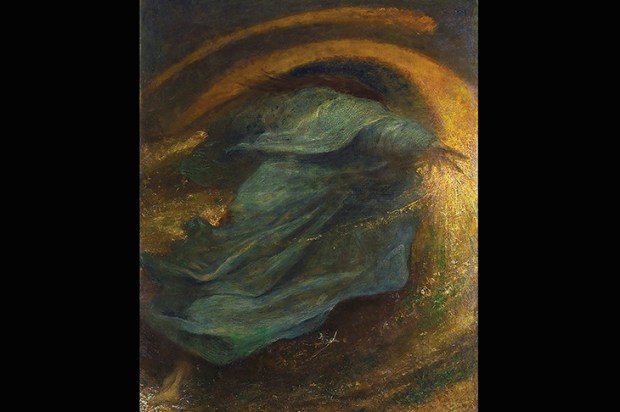

Actually, there was some justification for thinking the early works with which she made her name were on the ethereal side. ‘Music — Pink and Blue No. 1’ (1918) seems to show an arch made in some thin material such as linen or paper, through which a patch of sea- or sky-like blue can be seen.

Such pictures — and others, including ‘Blue and Green Music’ (1919/21) with various undulating waveforms in sickly pale green — might belong to the genre of ‘spiritualist abstraction’, in company with the works of the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint that were shown at the Serpentine earlier this year. There was also, however, from early on, another interpretation of O’Keeffe’s imagery, not so much transcendental as gynaecological. Her paintings, the artist Marsden Hartley noted, ‘are probably as living and shameless private documents as exist’.

O’Keeffe strongly resisted this line too, but that didn’t stop many people agreeing with Hartley. Much ink, the critic Robert Hughes remarked, has been spilled ‘on the topic of whether O’Keeffe ever set out to use specifically genital images’ (before spilling a little more himself). Her flower paintings — hugely enlarged close-ups of blooms and blossoms filling big canvases — are particularly liable to put observers in mind of private parts.

To deny the sexuality of one of her iris pictures, Hughes insisted, is ‘absurd, it amounts to not seeing the work itself’. I’m not so sure. After all, her horticultural canvases are very much like the oriental poppies, amaryllises and lilies they are supposed to represent (perhaps Hughes had not had a good look at those). So I’m agnostic on the sex question: my objection is that her work was very short of the joy of paint.

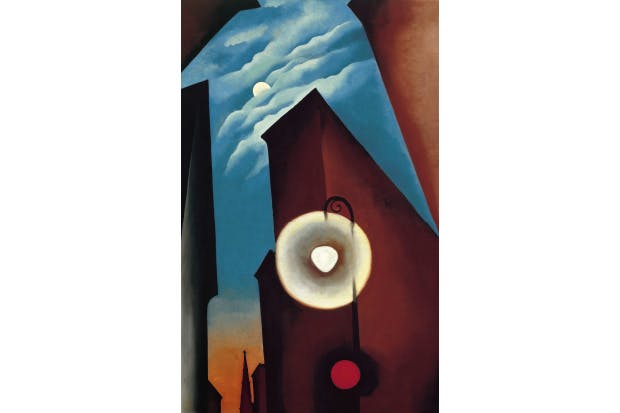

That is, the textures and surfaces of all her figurative subjects — whether flowers, Manhattan skyscrapers, bare hills in the desert of New Mexico to which she moved in the late 1920s, or the skulls of drought-stricken animals — were homogenised. They come out uniformly smooth, polished and seemingly paper-thin. This was, perhaps, the result of O’Keeffe’s close association with photography and its practitioners.

Her mentor, lover and eventually husband was Alfred Stieglitz, photographer and leader of the New York avant-garde. He was the first to exhibit her work, in the gallery called 291 (from its address on Fifth Avenue). Subsequently, she was the model — or perhaps ‘performance artist’ is a more apt description — in a remarkable series of pictures taken by Stieglitz, among them extremely sensuous nudes.

These are included in the exhibition, as are works by two other friends who were major photographers — Paul Strand and Ansel Adams. The results are odd. Usually, when paintings and photography are shown side by side, the former easily overwhelm the latter, having much more oomph and visual pizzazz. But O’Keeffe’s New Mexican landscapes, for example, don’t have the ruggedness or volume of black-and-white shots by Ansel Adams of the same subjects.

There is plenty to admire about O’Keeffe’s life — her energy, her determination, her sheer longevity (Van Gogh was at work when she was born; Jeff Koons was already well known when she died). However, a little of her art — much less than this exhibition contains — is enough. The critic Clement Greenberg complained in 1946 that her work ‘amounted to little more than tinted photography’. I think Greenberg got it in one.

The post Privates on parade appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in