This must rank as the most heartbreaking example of premature chicken-counting in musical history. ‘Gotter has made a marvellous free adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest,’ wrote poet Gottfried Bürger to the translator A.W. Schlegel on 31 October 1791. ‘Mozart is composing the piece.’ Three days later, brimming with misplaced confidence, the dramatist Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter confirmed that ‘the edifice is all ready to receive Mozart’s heavenly choruses’.

By 5 December 1791, Mozart was dead. Most probably, he never saw Gotter’s Tempest adaptation, although the musicologist Alfred Einstein stirred the pot of Mozartian myth by presuming that the master had set to work on it during his dying days. So the second most famous phantom opera drawn from the plays of Shakespeare evaporated into fantasy before it had even begun.

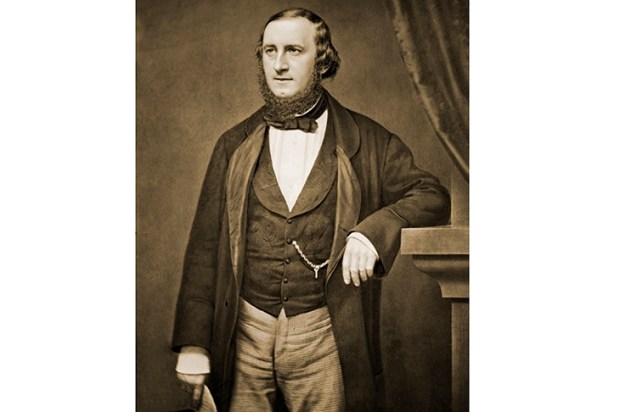

As for the best-known unbuilt blueprint, it has a more tangible history. Over a quarter-century, Verdi’s long-planned, never-executed opera of King Lear went through two librettists (Salvadore Cammarano and Antonio Somma), a handful of false starts, a posse of disappointed opera-house managers (starting with Benjamin Lumley in London in 1846) and numberless dark nights of the composer’s soul. Eventually, Verdi gave up on the storm-battered king and instead conquered the scarcely less formidable peaks of Otello and Falstaff. You might argue that Lear’s bond with Cordelia, which obsessed Verdi, also colours the great music for the jester and his daughter Gilda in Rigoletto.

These twin might-have-beens, their heavenly harmonies forever drifting just out of earshot, epitomise the lure of perfect Shakespearean opera. In this anniversary year, directors and programmers have rammed their seasons full of musical Shakespeareana. The 2016 Proms alone offer a dozen Bard-based concerts, from crowd-pleasing staples such as Mendelssohn’s skittering soundtrack to A Midsummer Night’s Dream to a brace of lesser-spotted takes on Lear itself: Berlioz’s concert overture, and Debussy’s fragments of incidental music.

Meanwhile, opera houses have plucked assorted rarities from the 300-strong inventory of Shakespearean music-dramas. On23 July, Glyndebourne will begin its run of Béatrice et Bénédict by the Bard-worshipping Berlioz — his version of Much Ado About Nothing. Weirder obscurities have resurfaced. When the youthful Richard Wagner watched Das Liebesverbot — his surprisingly jaunty opera of Measure for Measure — crash and burn on its ill-starred debut in 1836, he must have thought it sunk for good. This spring it popped up, under Ivor Bolton’s baton, at the Teatro Real in Madrid.

Even Il Re Lear itself has begun to hover on the brink of incarnation. Last November, the Lenz Foundation theatre in Parma put on a sort of multimedia revue inspired by Verdi’s sketches and outlines for the projected work. No one, to my knowledge, has attempted a full-scale Mozartian pastiche of The Tempest. But Simon McBurney’s staging of The Magic Flute for ENO and Netherlands Opera in 2013 treated its metaphysical cabaret as a sort of unconscious prelude or preparation for the non-existent opera, with Sarastro as a prototype Prospero meting out ordeals and rewards. Premièred in September 1791, The Magic Flute would have alerted Gotter to Mozart as a prospective setter of the Tempest script. Post-Flute, he evidently looked like the go-to guy for a mystical pantomime.

Dream on. This brace of unwritten masterpieces still lures opera-lovers for whom the ideal Shakespearean drama teases and tantalises, as Ariel does The Tempest’s drunken mariners. However, the curtain never rose on a faithful, fully rounded Shakespeare opera, and never will. Even Otello itself, the nearest shot to a bull’s-eye, renders down the play’s dark heart — Iago’s ‘motiveless malignity’, in Coleridge’s phrase — into the villain’s upfront demonic manifesto: ‘Credo in un Dio crudel.’ Yes, it’s magnificent, but it isn’t really Shakespeare.

Opera and music-theatre composers tend to treat the texts with the same merry abandon as the playwright did his own sources. They plunder and ransack Shakespeare; they pimp him; they customise him; they cut him down and mash him up. Enduring music often grows out of misunderstanding, mistreatment and betrayal, all the way from the mischievous alchemy that Purcell’s The Fairy-Queen performed on A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1692, through to Thomas Adès’s and Meredith Oakes’s slimline compression of The Tempest in 2004.

Shakespeare in opera — maybe Shakespeare in music — amounts to a sonic landscape of ruins. It could be that the frankest, the most fruitful, adaptations acknowledge this smashed and pulverised incompleteness. In Luciano Berio’s Un re in ascolto, itself haunted by Mozart’s uncomposed Tempest, a production of that play forever impends but never quite happens. At this year’s Proms, on 27 August, soprano Barbara Hannigan will sing Hans Abrahamsen’s ravishing let me tell you: a rhapsodic song-cycle, first written as a novella by Paul Griffiths, which uses only the words that Ophelia speaks in Hamlet. Griffiths and Abrahamsen make a virtue out of shattered Shakespeare.

Yet the mirage of Absolute Shakespeare at the opera still beckons. In 1857, Il Re Lear was actually offered to the San Carlo theatre in Naples before Verdi changed his mind. In some alternative universe envisaged by a steampunk novelist, it reached the stage to thunderous acclaim. Through his detailed notes for Cammarano, you sense that Verdi can already hear parts of the work, whether the Fool’s bittersweet ditties, Edmund’s Iago-like aria to pitiless Nature, or the Act 3 finale that reunites Lear and Cordelia. ‘Lear awakens. Magnificent duet, as in Shakespeare’s scene. Curtain falls.’ How much of the entire operatic repertoire would you sacrifice for the chance to hear that scene?

The post Where should this music be? appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in