Threnody. Dirge. Lament. Epitaph. Elegy. Wake. There are so many English terms to describe the passing of people and things that you wonder if introspection about demise might be a national characteristic. All these words are on my (doggedly cheerful) mind as staff have moved out of London’s Design Museum, securing the last open door with a padlock on 30 June and leaving inside cavernous spaces with rusting memories of designer people and designer things.

So what was the old Design Museum? It arose from a conversation between Terence Conran and me in 1978. He was the proprietor of Habitat, whose decent, modern merchandise revolutionised popular taste, and I was the author of a book about design he had just discovered. He was about to revolutionise me by asking for help to make something that would be as useful to contemporary students, from the point of view of inspiration, as the old V&A had once been to him.

Our prospectus began with a series of popular exhibitions in that august old museum and then we built a spiffy new one of our own. Mrs Thatcher opened it in August 1989 at Butler’s Wharf, just southeast of Tower Bridge. At the time, the glorious view of the City included only Seifert’s NatWest Tower as a punctuation mark on the horizon. Two year’s after Big Bang, the mood was still very Eighties. And so, too, I now see, was the character of the Design Museum.

Terence Conran’s great achievement, although he does not perhaps see it this way, was to elevate design from an activity to a commodity. It was no longer something artisans did — whittling a stick, for example — but something that consumers could acquire. It was about fine things enjoyed by civilised folk. It was all about moral certainties and aestheticised hedonism. Conran was adamant about these certainties: looking at Casa Pupo, the OKA of its day, he would insist that it was not design when, of course, it was. Just not his sort of design. He has always been reluctant to acknowledge the role of taste in his own judgments.

Still, he made douceur de vivre accessible, at least in fantasy. A scrubbed wooden table from a French monastery, a coarse glass jug holding a single daffodil stem, a Bauhaus chair, a French white porcelain batterie de cuisine and modern jazz from a Dieter Rams SK4 record player. There was more to it than that, but you get the picture. Many did. Yet even at the time there were competing definitions of design, some of them my own, but this was one I liked very much so, ker-ching, off we went.

We had found an old 1940s banana warehouse with a tough concrete frame and low floor-to-ceiling heights which made no concessions whatsoever to charm or delight, but had potential for creative reuse. The design of a Design Museum became an amusingly self-reflective task. The architect was Stuart Mosscrop, a ferret-eyed fanatic who, the decade before, had used lasers to make sure the horizontals of his enormous Central Milton Keynes Shopping Centre were all true, the better to discipline shoppers. I liked that sort of thing.

We worked with an engineer called Frank Newby, who had helped create the Skylon at the 1951 Festival of Britain and had interned with Charles Eames in California. This was a good team. And there were several other connections to the spirit of 1951. Like the majestic Royal Festival Hall, the Design Museum was sited in a desolate part of London and intended to catalyse a local revival in Michael Heseltine’s Docklands project. But as in 1951, when the Skylon was not aerospace technology but fabric and string, there was a little bit of Potemkin Village bluster about the building: it was, in truth, rather grander than the underlying reality.

The period details are telling. The architect, engineer and I went away to Shipdham Place Hotel, belonging to the elegant Justin de Blank, London’s ‘celebrity grocer’. Here, in rural Norfolk, we spread rolls of drafting paper on the floor, gripped our magic markers, ordered some good red burgundy and agreed the general arrangements of the world’s first museum of mass-produced design. What we decided was to remove some of the banana warehouse’s concrete slab floors, build on the roof, render it blinding white and, all-in-all, create what people later called ‘Bauhaus on Thames’. The interiors were by Paul Williams and Alan Stanton, among the first jobs of a practice that has since won huge international esteem.

But by 2004, long after my time, control of the Design Museum was on vectors of escape from the earthbound purity of its original intentions. An exhibition about the flower arranger Constance Spry, who led the team that created ‘Coronation Chicken’, caused a frightful spat. Conran felt betrayed by trivia and James Dyson resigned from the board in a technophiliac huff. A woman who thought about housing policy was lionised in an exhibition. In the absence of authentic new design heroes, architecture itself became subject for scrutiny. Fifteen years after its opening, design was acquiring so many meanings that it was becoming meaningless, while the Design Museum was becoming muddled, even as it became ever more popular.

And this process continues: globalisation has blown away assumptions about the priority of Eurocentric criteria. We have open-source design, critical design, feminist design. With the off-shoring of manufacturing, fugitive ‘brands’ have become more valuable than the actual products they represented.

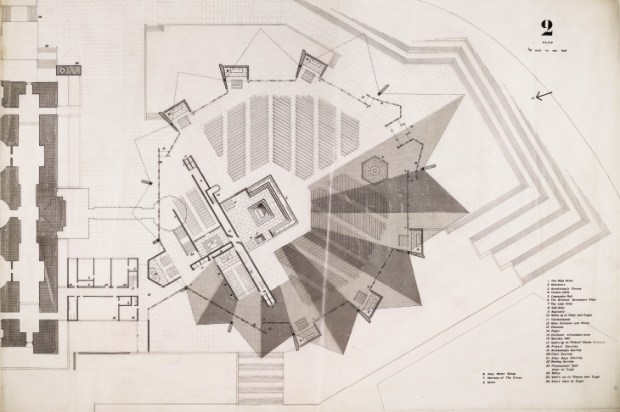

In this embarrassment of confusion, it was decided to move the Design Museum to larger premises, although, to be honest, its managers had had difficulty filling the existing building with meaningful material. There was a flirtation with the Tate, but Nick Serota outsmarted them and it came to nothing. Or rather, it came to the Tate’s new Herzog and de Meuron building instead. Then, as the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea found itself in need of offloading the decaying and obsolete Commonwealth Institute, on the rebound, the Design Museum offered to refurbish it.

It was an irresistible offer because Terence Conran, still the Design Museum’s major patron, is tempted by new challenges, even when old challenges have not been quite resolved. Thus, Ingvar Kamprad, the founder of Ikea, acquired Habitat when Conran had lost interest in it. Once Kamprad asked Conran in charmingly stilted English: ‘When shall you learn to take care of what you already have and not only put new activities on your desk?’ The honest answer would have been ‘never’.

The new Design Museum, which opens in November, does two unwelcome things: locate ‘design’ on a nasty shopping street and confirm a suspicion that, even in his eighties, Conran’s restless ambition may be getting the better of his remaining good sense. But while the old Design Museum perfectly reflected a shared set of beliefs, the new one will only be a partial witness to its patron. Conran should, perhaps, be more wet-eyed than me. Sometimes we can remember things only as a sense of loss.

I am left unsure if ‘my’ Design Museum was the end of something old or the beginning of something new. Auden thought love would ‘last for ever’ and I felt much the same about the curious little modernist building on Shad Thames. A temporary monument? Indeed, a pop-up museum! It’s a bittersweet, darkly humorous thought. But Auden also had views on the clean lines of the Design Museum’s founding philosophy:

Preserve me from the Shape of Things to Be

The high-grade posters at the public meeting

The influence of Art on Industry

The cinemas with perfect taste in seating.

Oh, yes. I could have repeated that at closing time. Or possibly, if in a more sombre and reflective mood, the morbid kitsch of A.E. Housman’s ‘To An Athlete Dying Young’:

Smart lad, to slip times away

From fields where glory does not stay

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

It’s not quite over for the original Design Museum. With startling incongruity, the severely rectilinear building was bought by the commitedly organomorphic Zaha Hadid shortly before she died. So thus an empty shell now becomes a monument twice over.

On 30 June, I thought of taking a few friends and a few bottles to the riverside site to contemplate ‘Ozymandias’. I also thought about Prince Charles, who witheringly asked me ‘Why does it have a flat roof?’ He’ll be pleased that the hyperbolic paraboloid in Kensington has no such thing. And he’d be amazed how touching concrete can be.

The post Requiem for a designer dream appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in