In a piece of light verse from the 1770s ‘Dame Nature’ — out strolling ‘one bright day’ — bumps into the great landscape designer, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. Immediately the goddess lays into him for plagiarism. How, she wants to know, does he have the impudence to show his face? All the items he claims to have created — ‘the lawn, wood and water’ — were made in fact by her.

Brown, for his part, is not at all disconcerted. He admits that Nature has provided him with good raw materials. But the beautifying refinements? Those are all his. ‘The swell of that knoll,’ he points out, ‘is mine… the ridges are melted, the boundaries gone.’

Rather ungallantly, he asks Nature to admit, ‘I have cloth’d you when naked, and when overdrest, I have stripp’d you again to your bodice and vest.’ In short, he has improved on nature: ‘concealed every blemish, each beauty display’d’. He had worked, indeed, much like a painter such as Claude Lorrain, but fashioning his pictures with real earth and living trees.

This month, as we approach the tercentenary of his birth on 30 August 1716, the case for and against Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown remains much the same. His supporters feel he did improve the scenery surrounding many great houses, indeed transformed it into a work of art. His opponents — and they remain numerous — continue to protest that Dame Nature’s landscape was preferable before Brown started excavating, draining, planting and flooding artificial lakes. There is an argument for believing Capability Brown was the most influential of all British artists, but — some would add — also the most pernicious.

For good or ill, he was certainly industrious and enthusiastic; famously that nickname derived from the way he strode about each new estate to be improved, discovering ‘capabilities’ all around. On his instructions, earth was moved in prodigious quantities. To form the Grecian Valley at Stowe, for example, as the National Trust website approvingly records, 240,000 cubic yards of soil — equivalent to the volume of 1,631 London double-decker buses — was shifted, all with spades, horses and carts. If they spoiled the prospect, whole villages were demolished, and their inhabitants moved (though not, admittedly, only for Brown’s projects; this was a habit of Georgian landowners). Trees were inserted by the thousand, streams dammed, lakes formed, antique-looking temples and, as at Wimpole, brand-new ruined castles built.

Over a long career, Brown made designs for over 170 parks, making himself a fortune in the process. The fifth child of a Northumbrian land agent and a chambermaid, he earned the equivalent of three quarters of a million in today’s money. Reportedly, he refused to work in Ireland on the grounds that he had not yet finished England. He died, in 1783, lord of the manor of Fenstanton in Huntingdonshire.

Some would say, however, that with immense effort Brown had made the settings around the great houses of England a bit more dull. The acid-tongued proponent of the picturesque, Richard Payne Knight, complained of Brown’s ‘bare and bald’ style with its clumps of woodland and swathes of grass sweeping up to the great house.

Payne Knight and his regency contemporaries wanted their landscapes to be romantically poetic — either rustically or sublimely. In contrast, Brown had turned parks into Augustan prose. He even talked about it in terms of punctuation. Chatting to the writer Hannah More, he explained how when designing a landscape he inserted the visual equivalent of a comma — a single tree perhaps — if a small pause was required. When ‘a more decided turn is proper’ he put in a colon, or ‘where an interruption is desirable to break the view, a parenthesis’.

When he’d finished, it all flowed smoothly, but by no means everybody likes their countryside arranged into orderly Georgian sentences. Richard Mabey put the prosecution view eloquently in a New Statesman essay. ‘The claims made [for Brown],’ he wrote, ‘are of breathtaking hubris: “creating harmonious pictures with the land itself”. Whose harmony? Whose land?’

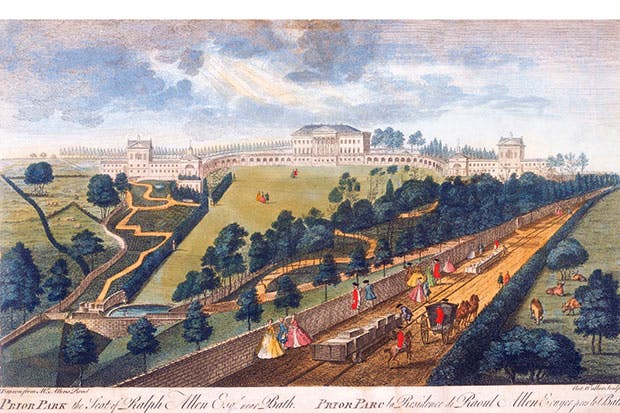

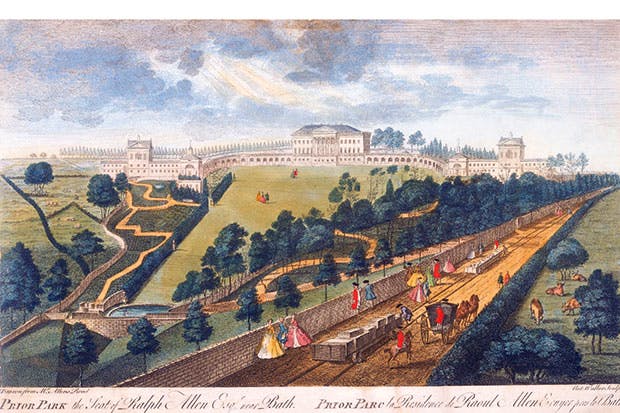

I half agree. The trouble with Brown was that he was so energetic. He did not invent the ‘natural’ style in gardening, that honour belongs to predecessors such as William Kent. But he offered a wonderfully efficient service for implementing it. In the process, innumerable earlier formal gardens were swept away. As the fashion for the English garden took hold, much the same happened all over Europe.

Personally, I regret the loss of all that topiary and those geometric beds. But I don’t think you can argue, as Brown’s critics are tempted to, that his 18th-century parkland is somehow less ‘natural’ than what came before. For many millennia human beings have been rearranging the terrain of this country in one way or another. One may or may not love the way Lancelot Brown remodelled the land — though, while wandering around the Grecian Valley at Stowe on a bright day, it is hard not to do so. But the point about the goddess Nature is that she is a mythical being.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in