The bad news for old rock’n’rollers is that there’s not much time left to stay at Heartbreak Hotel — these days located not at the end of Lonely Street, but on Elvis Presley Boulevard, Memphis. In October it will close, to be replaced by the demurely named Guest House at Graceland: in reality a swanky new hotel with nearly twice as many rooms as the Dorchester.

But this is only the latest addition to Elvis’s former pad since the operating rights were bought by the Authentic Brands Group in 2013. Already Graceland has an expanded visitor centre, and the tour of the house now comes with a rather good iPad commentary that mixes the calmly factual (‘Beyond the stained-glass peacocks is the music room’) with moments of historical analysis (‘Another classic Seventies touch is the green shagpile carpet on the floor — and the ceiling’). Its closing summary that ‘every dream Elvis had was fulfilled 100 times’ is perhaps a little rosy: he might, for example, have dreamed of living beyond 42. Nonetheless, you do come out with the undeniably thrilling impression of having been in his presence.

And if you want a similarly intimate sense of how Elvis got to Graceland, you don’t have to travel far. At Sun Studio in downtown Memphis, where his career began, you can walk on the tiles laid by the studio’s owner Sam Phillips, see the cigar burn left by Jerry Lee Lewis on the low E of the studio piano, and pretend you’re revolutionising music by posing with the very microphone that Elvis used on the very spot where he used it. You’ll also get the whole Sun story, told with awed enthusiasm by a guide who emphasises that you’re standing on ‘sacred ground’.

For some cities, that might be enough commemoration of musical greatness to be going on with. Not, though, for Memphis — which is increasingly putting almost all its tourist eggs in the music basket. In more recent times, Graceland and Sun Studio have been joined by the worthy but definitely not dull Memphis Rock ’n’ Soul Museum, the only branch of the Smithsonian outside Washington; and by the huge and impressive Stax Museum of American Soul Music, built on the patch of cracked concrete and weeds where the original Stax studio once stood and recorded the likes of Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes and Booker T. & the M.G.’s.

Meanwhile, two more music museums have opened in the past year alone. At the Blues Hall of Fame, the somewhat uncompromising exhibits include Little Walter’s harmonica and Koko Taylor’s boots. At the Memphis Music Hall of Fame, director John Doyle is currently hoping to add Isaac Hayes’s mah-jong set to his collection. So what, I ask him, would Memphis be without its music? ‘Nothing,’ he replies.

But why, you may be wondering, has it taken the city so long to capitalise fully on its unmatched status as the cradle of 20th-century popular music? In this case, the answer isn’t merely the traditional uncertainty about pop music’s shelf-life. (As a teenager in 1970s Liverpool, I’d often see American and Japanese tourists wandering around looking for Beatles sites — and being amazed to learn that there weren’t any.) Instead, the main reason can be dated with some precision to 6.01 p.m. on 4 April 1968: the moment when Martin Luther King was shot.

In theory, King could presumably have been assassinated in any other American city. The trouble is that he wasn’t — and the resulting combination of riots, shame, white flight and racial tension (even at Stax, where black and white musicians played together, mutual suspicion set in overnight) made for what many thought was a terminal crisis. ‘Dr King’s assassination,’ recalls Tim Sampson of the Stax Museum, ‘was like 9/11 in Memphis’ — except that New York recovered far more quickly. ‘When I graduated high school in 1977, only two downtown bars were left, and Beale Street was all boarded up.’

The changing fate of Beale Street, in fact, is a useful guide to the city’s as a whole. Before civil rights, it was the commercial centre of black Memphis — and with its black dentists, insurance companies and banks, proof of how thorough segregation was. More famously, black musicians from across the South performed there (many places claim to be ‘the Home of the Blues’, but only Beale Street has had its claim endorsed by an Act of Congress) — and although white people didn’t go into the clubs, the more adventurous of them, including Elvis, listened outside.

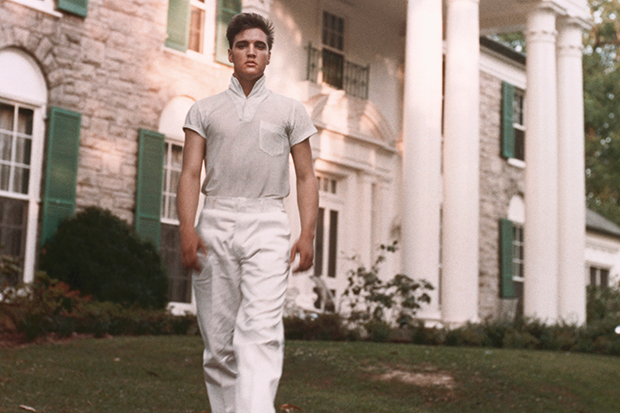

Now Beale is bustling again, this time with tourists, and if the music there has an unmistakeable heritage feel, that doesn’t make it any less stirring. Two years ago, Beale also saw the return of Lansky’s clothing shop, which supplied Elvis with his early outfits — hence its slogan of ‘Clothier to the King’ — and now sells copies to today’s punters. Hal Lansky, the current owner, also points out the possibly underrated influence on country music of 19th-century British royalty. Back when the young Hal was working for his dad, Johnny Cash came in with a tobacco tin featuring Prince Albert in a long black coat, and asked for one just like it. And with that, the Man in Black was born.

Needless to say, all this makes Memphis a dream destination for any music lover. It doesn’t, however, necessarily guarantee a happy ending to the city’s recent history. For one thing, it’s hard not to notice a continuing racial nervousness in the careful understatement of the museum captions. According to the Smithsonian, ‘Memphis shared in the nation’s struggle for racial equality’ — which is one way of putting it. In Stax, we’re told that the reaction to America’s first black radio station, based in Memphis, ‘was overwhelmingly positive, except for the requisite racist bomb threats’. (In an unguarded moment, someone in Memphis tourism expressed to me his fear that it might only take one trigger-happy white policeman for the city to fall apart again.)

For another, there’s the question of how long-term this music-centred strategy will prove to be. In 20 or 30 years, will anybody still be interested in Otis, Isaac or even Elvis? There is, you’ll notice, no tourist industry based around Al Jolson.

But of course this is also an argument for the place to cash in while it can — and, after the decades-long trauma caused by Martin Luther King’s death, who can blame it? These days, Memphis could certainly be accused of making quite a fuss about its own music. Then again, there’s an awful lot of Memphis music worth making a fuss about.

The post All the way to Memphis appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in