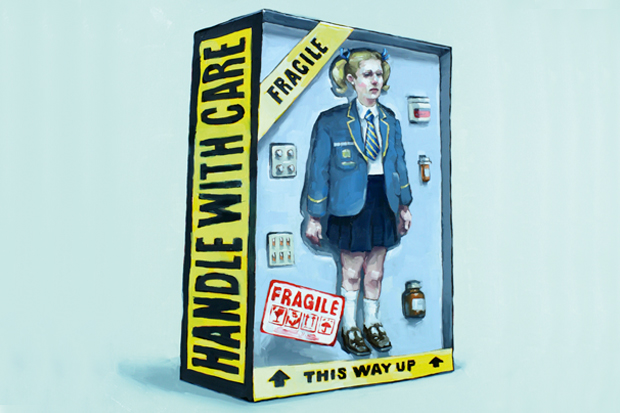

It was recently exposed in News Limited newspapers that as many as one in three students in some elite high schools were receiving disability provisions, primarily around anxiety or depressive disorders. This usually took the form of extra time, their own room or added supervision. Sometimes they are given extra marks for examinations they are not able to complete.

The story itself was headlined in a way to suggest that elite schools may be gaming the system, but a headmaster of one of the private schools suggested it had to do with middle class parents being more aware of their rights and privileges.

One headmaster, John Collier, from Sydney private school St Andrews offered a statement that adolescents were not quite what they were in tackling adversity: ‘Teenagers are less resilient than they were a generation ago, and more likely to fold and seek professional assistance.’

Statistics certainly bare this out with an increase in mental health presentations among adolescents. It partly represents a greater cultural focus on explaining all distress through the lens of mental health rather than normal responses to adversity or not being able to accept some aspects of poor performance as weakness in personality to be steadily worked upon.

School counselors and adolescent psychologists cite everything from more fragmented families, a poorer tolerance of failure and a greater focus on material success on why our children seem more brittle in the face of pressure. Indeed, US studies found that asked if becoming rich was a priority for the future, teenagers responding yes had more than tripled from 25 to 75 per cent in three decades.

But the deeper challenge reflects the broader crisis engulfing Western society and the modern condition, how to converge such disparate groups in a largely post-religious society and still allow for the formation of strong collective identities. Adolescents are particularly sensitive because it is the stage of life they search for belonging. This is not a question yet to be solved. I am asked to fill out such disability forms every other day, usually for children of middle class parents in suburban Sydney. The questions are whether the patient may benefit from privileges such as extra reading time or scheduled breaks. Unsurprisingly, the answer is usually yes, which I suspect would be the answer for children who do not attract any diagnosis.

There is usually an extra urgency when the time of examinations draw near, as they are now with the imminent end of high school. While the majority of presentations are around anxiety disorders, there are also many parents seeking stimulants and a diagnosis of attention deficit, believing drugs like Ritalin and dexamphetamine may improve their child’s performance at the critical, home straight of high school. The pattern illustrates several contemporary changes, channeled through trends in mental health.

One is that the middle classes are more likely to access specialist mental health care as part of a broader project of success and self improvement. The intense meritocracy of the modern age and emphasis on professional success reaches a social zenith in late high school.

The working classes are more likely to access mental health care under duress from school, work or welfare and bodies. The disability provisions in schools are increasingly becoming a form of middle class welfare; parents of children in public schools have a right to feel cheated.

Another is that there have been broad trends in emphasising self esteem, reducing the primacy of competition and, through programs like Safe Schools, producing an environment that paints children as vulnerable and requiring protection from malevolent outside forces, be they bullies, racists or excessive competition. A significant portion of elite private schools, such as Geelong and Knox Grammar, now have programs emphasising positive psychology. On their website Geelong refer to this program as enabling kids in ‘feeling good and doing good.’ In my experience, such a philosophy doesn’t always prepare children for inevitable failures and difficult emotions. It is partly an example of what American psychiatrist and author of One Nation Under Therapy, Sally Satel, calls therapism. She defines this as a growing sense that people are emotionally fragile, lack agency and require professional help to negotiate the challenges of ordinary life.

The other unspoken element is that middle class, usually white, children from elite private schools are competing with highly motivated, goal-directed children in public selective schools who are now consistently outperforming them in academic results. For example, last year in NSW, public selective schools represented the top eight before the first private schools, Abbotsleigh and Sydney Grammar, showed up in 9th and 10th places.

What this represents are fundamentally different views of human nature clashing through our school system. The predominantly Asian parents of children in public selective schools, as popularised through the notion of Tiger Mums, are unashamedly elitist, see children as resilient and able to cope with pressure, view intense competition as a social reality and are sceptical of the notion of self esteem separate from actual achievement. The area they underestimate is the importance of social and communication skills, particularly in service economies where technical skills can be outsourced but creativity and soft skills are more highly prized. You can bet they’ll catch up quick.

The growing Western emphasis on children feeling good about themselves and decrying the hothousing of Asian children through weekend coaching is brought into sharp focus in late high school when there appears to be a delayed realisation that certain marks are required to enter the most elite, attractive university courses. Some of this can be bypassed through paying fees or interview only courses, but the reality of raw performance under pressure and intense competition can come as a rude shock. The statistics surrounding the considerable rise in disability provisions for children of wealthy parents underline this trend and raise new challenges for ensuring equity of opportunity for chidren.

The post Mental mollycoddling appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in