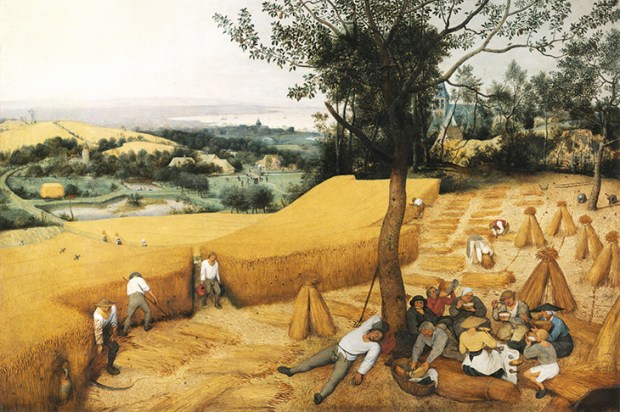

It was the brightest of futures; it was the End of Days. Three hundred and fifty years before Brexit, England experienced a series of epochal events which forced subjects to rethink their relationships with each other, their political leaders and their European neighbours. In the space of a tumultuous 12 months England endured the devastation of plague, the most humiliating of naval defeats at the hands of the Dutch, and the catastrophe of a Great Fire which transformed its capital city forever. Where there was a commonly held view, espoused by humble parish clerks and vociferous dissenters like George Fox alike, that the cataclysms revealed God’s wrathful judgment upon a sinful nation, there were others who saw in catastrophe an opportunity to build afresh: Andrew Marvell repurposed satire in his ‘Advice to a Painter’ poems; Christopher Wren reimagined the verybasis of London itself.

Rebecca Rideal and Alexander Larman both offer accessible and entertaining commemorations of this historical moment in their new books. While their accounts have many affinities — chiefly a narrative emphasis on individual historical characters — they frame the central event of the Great Fire in different ways. Rideal offers a chronological survey, beginning with the explosion of a ship forebodingly called The London in the Thames estuary in March 1665, before moving through a series of historical snapshots: the onset of plague and the exodus of about 30,000 people from the capital in July 1665; the Second Anglo-Dutch war and the Dutch naval victory in the Four Days’ Fight in June 1666; the start of the Great Fire in Thomas Farriner’s bakery on Pudding Lane in September 1666.

Larman covers much the same ground but arranges his material into short chapters on the court, religion, science, disease, entertainment, fashion and taste, crime and international relations as a means of taking the temperature of London before it burst into flames in 1666.

Both authors share a keen eye for engaging anecdote and historical personality. Larman reminds us that Pepys was particularly keen to salvage his parmesan cheese as the flames burned on 4 September (parmesan, as a luxury commodity, was then well worth saving). He examines Restoration sexual mores with a thumbnail sketch of the brothel-keeper, prostitute and entrepreneur Damaris Page, so successful at meeting the needs of London’s seamen that she became the subject of several Grub Street pamphlets.

Rideal, likewise, enlivens her description of the religious paranoia engulfing London after the Great Fire with a grim anecdote about an anonymous Frenchwoman in Moorfields who had her breasts cut off after the chickens she was carrying under her apron were mistaken for fireballs. (Foreign nationals living in the capital were at risk from mob violence in the immediate aftermath of the fire because of rumours that the French or the Dutch had deliberately started the blaze to destabilise the regime.)

For all such narrative colour, how-ever, readers hoping to encounter a radical reassessment of the events of 1666 in these books will be disappointed: despite the xenophobia and religious intolerance, the fire was started accidentally; it was stoked by a very hot summer, timber building materials and some ineptitude on the part of Sir Thomas Bludworth, Lord Mayor of London; casualty numbers were, officially, astonishingly low, at six or eight people, but are impossible to fix with certainty given the fire’s likely destruction of the evidence.

There is nothing here to disturb the authoritative accounts of these events offered by Adrian Tinniswood’s By Permission of Heaven (2004), Stephen Porter’s The Great Fire of London (1996) or Walter George Bell’s magisterial diptych The Great Fire of London (1920) and The Great Plague of London (1924). Rideal uses her sources carefully, always citing the latest research and providing footnotes for all citations and statistics. She has a lengthy persuasive note, for example, on the epidemiology of 17th-century plague, discounting recent suggestions that it was Ebola, anthrax, typhus or an extinct disease in favour of the mainstream view that it was ‘a virulent strain of bubonic plague with rat fleas as the primary vector’. By contrast, the absence of footnotes and endnotes in Larman’s book, and its very slender bibliography, invite scepticism about the claims he makes.

The breeziness of Larman’s prose means that some of those claims are unhelpful or misleading. Hull is described as the ‘northeastern neighbour’ of Liverpool, which is almost as absurd now as it was before the advent of the M62. ‘Other than drama,’ Larman contends, ‘the most common form of entertainment in 1666 was prostitution.’ This is a silly assertion to make about a deeply religious society like early modern England, of course. But it’s particularly problematic when we recall that Pepys, lover of all things extramarital, never once retained the services of a prostitute, according to his diary, even if he enjoyed watching and flirting with the sex workers of Fleet Alley. A similar problem occurs where Larman uses a civil-war source — Henry Peacham’s The Art of Living in London (1642) — to describe women’s fashions in post-Restoration London, which is a bit like trying to capture contemporary sartorial trends by consulting a heritage issue of Marie Claire.

Given the climactic nature of 1666 as a year in which London was reduced to ashes, re-planned and reborn, both books might have done more to nuance an outdated image of Charles II as a ‘merry monarch’, swiving his way around his kingdom as his libido dictated. The king was, for all his prodigious sexual appetite, keenly involved in the grand building plans for post-fire London and had been a fan of Christopher Wren’s architectural ideas long before he appointed him surveyor of the king’s works in 1669. Even though Wren’s grand plans for a new London were not adopted due to financial constraints, the king’s interest in the capital’s religious and civic architecture helped redefine the tense relationships between city, church and crown in this most fascinating of periods.

The post One scorching summer long ago appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in