They say that the devil gets all the best tunes, and on the basis of this week’s opera-going it would be hard to disagree. Performances by Cape Town Opera and Opera Rara turned their attention on two historical icons: South Africa’s anti-apartheid campaigner and president Nelson Mandela, and ancient Assyria’s murderous and would-be incestuous queen regent Semiramis. No prizes for guessing who came out on top. When it comes to art, evil takes it nearly every time. Who wouldn’t choose The Rake’s Progress over The Pilgrim’s Progress, Don Giovanni over Don Ottavio, sex over sanctity?

For a good man, Nelson Mandela has inspired a lot of really, really bad art. Just think of the various biopics, the Dean Simon reimagining of the Last Supper with Mandela as a muscular Jesus, even Richard Stone’s iconic portrait — all soft-focus, pastel idealism. Where life is so vivid, so virtuous, it leaves art nowhere to go, a problem that the Mandela Trilogy in all its affirming, essentialising optimism fails to resolve.

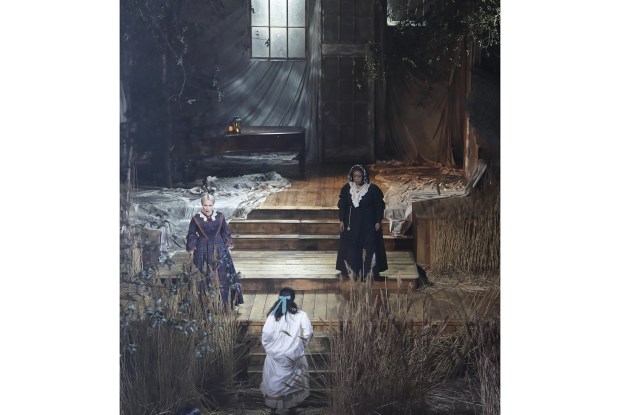

A lot has changed since the show first appeared in Cardiff in 2012. Three composers have become two, a sprawling orchestra and cast have shrunk, and dramatically things are a lot tighter. But still the Mandela Trilogy cannot make up its mind what it is. Mike Campbell’s jazz- and rock-infused Act II clearly wants it to be Mandela: The Musical — South Africa’s answer to Evita — and judging by the audience response, this would be a winner. But Peter Louis van Dijk’s framing Acts I and III aspire to something altogether loftier: a translation of the Mandela story into the musical tropes and textures of western art music.

To ignore the irresistible swing of Sophiatown jazz or the thrilling energy of indigenous Xhosa music for something so blandly efficient — an inoffensive fusion of sub-Copland string writing and Philip Glass ostinati, whose big brass climaxes all sound like the theme tune to an Aaron Sorkin series — is criminal. Why borrow someone else’s musical language when your own says it best? It’s telling that the moments where this show really works — the a capella female chorus in Act III; the slinky arrangement of Miriam Makeba’s 1957 hit ‘Pata Pata’ — are those most straightforwardly South African.

Performances are almost as mixed as the material itself. At one end you have the blissful excellence of the Cape Town Philharmonic, 12 ensemble and Cape Town Opera’s chorus (the latter all the more impressive given the current, widely reported conflict between singers and management over a question of financial exploitation of black singers), while at the other principals defeated by the score’s bewildering range of technical demands and director Michael Williams’s mawkish text.

Of the three Mandelas, only Act III’s Mandla Mndebele has the vocal authority to carry the role, and both classically trained Siphamandla Yakupa (Winnie) and musical theatre’s Candida Mosoma (Dollie) struggle when asked to move beyond the boundaries of their own styles. It’s hard to shake the feeling, given the often ungrateful vocal lines and the new reliance on spoken narration, that Williams’s vision wouldn’t have been better served as a Lincoln Portrait-style symphonic work than as an opera. Compare it to a piece like Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, an opera rooted in similarly vernacular, popular styles of music, and you see the problem. Where the latter dissolved American blues and jazz into a distinctive, coherent soundworld, the Mandela Trilogy feels like a tourist in its own musical landscape, leaving musical ideas and impressions curiously fragmentary and undigested.

Rossini’s Semiramide is a challenge to even the world’s top opera houses. Running at well over four hours and demanding at least three singers of superhuman vocal strength and agility, it’s not a work you tackle lightly. Enter Opera Rara, the little record label who could. Canny repertoire choices and superb casting have helped this enterprising outfit return many a work to the popular canon, and if this concert preview of its latest release is anything to go by it’s done it again.

Conducting the period instruments of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Mark Elder delivered a lean, mean version of Rossini’s epic score. Brass were querulous, wind acid, and the whole effect wonderfully pacy. But it’s the cast that will win this recording awards.

Soprano Albina Shagimuratova — an unlikely piece of casting for the low-lying Semiramide — may never have taken a bel canto role before, but here she establishes herself as a future star of the genre, a singer who might well have solved the Royal Opera’s recent Norma problem, had they only known. Supported by the reliably astonishing mezzo Daniela Barcellona’s noble Arsace and Gianluca Buratto’s sonorous priest Oroe, she led an outstanding ensemble cast, offering a portrait of human weakness and wickedness far closer to Shakespearean tragedy than many of us give Rossini credit for.

The post Saintly sins appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in