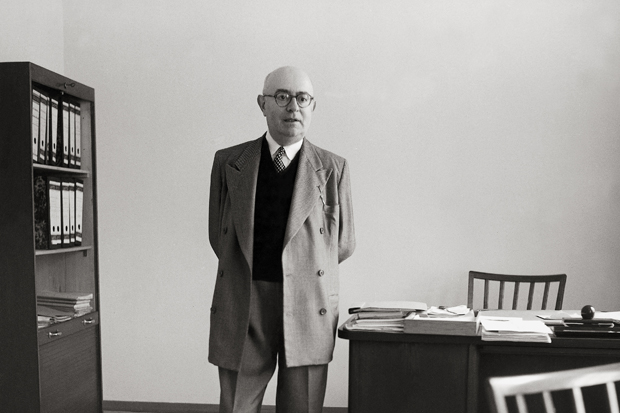

One day in April 1969 Theodor Adorno began teaching a new course entitled ‘An Introduction to Dialectical Thinking’. Feel free, the sociologist-cum-philosopher told the packed hall at Frankfurt University, to ask questions as I go. Two of his charges did so immediately. When was Adorno going to apologise for having set the cops on those campus protesters three months earlier? Before Adorno could reply, another student scrawled ‘If Adorno is left in peace, capitalism will never cease’ on the blackboard. At which point the whole class shrieked ‘Down with the informer!’ Then a group of women surrounded Adorno, bared their breasts, and showered him with rose petals. Grabbing his hat and coat, the hapless prof ran.

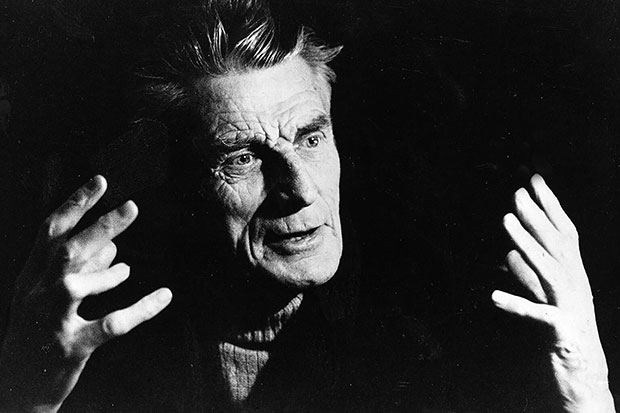

I’d love to say welcome to the Frankfurt School, but as Stuart Jeffries’s sometimes sprightly, sometimes suety, collective biography of its founders makes clear, life was rarely very exciting there. Founded in 1923, the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research was a place of fearsome seriousness. Its key thinkers — Adorno, the philosophers Herbert Marcuse and Max Horkheimer, the psychologist Erich Fromm and, more tangentially, the critic Walter Benjamin — were obsessed with the failure of the German Revolution of 1919. By marrying the early Marx’s social theory to Freudian psychoanalysis, they hoped to understand why the working classes had renounced socialism for ‘modern consumer capitalist society and [subsequently] Nazism’.

It wasn’t an easy marriage. Among its progeny were those airheaded adolescent insurrectionaries Adorno was assaulted by. Freud and Marx were such different thinkers that no responsible church would ever permit their union. As Jeffries points out, while Freud’s view of human nature was essentially tenebrous, Marx’s was almost facetiously sunny. Whereas Freud argued that repression was the painful price we paid for civilisation, Marx believed that the freedom capitalism’s inevitable demise would usher in would make man not only whole, but wholly good.

In fact, these differences went further than Jeffries allows. Wide-ranging as Freud’s theories were, they were also tightly tethered to the particular. He thought you were explicable by reference to the unconscious dreads and desires engendered by your ineluctably conflicted relations with your parents. But for Marx such talk of individuated existences was bourgeois tosh. He saw you as an expression of whatever class structure you’d been born into. As for the surreptitious sway of the unconscious, forget it. Not even your sentient mind has that much clout: ‘It is not the consciousness of human beings which determines their existence,’ wrote Marx, ‘but their social existence [which] determines their consciousness.’

False consciousness was what really got the Frankfurters’ goat. They couldn’t understand, says Jeffries, why people not only eschewed radicalism but seemed ‘delighted… with the chains that bound them’. In America, where the School was obliged to set up shop after Hitler’s rise to power, they found the masses even more gullible. Dismissing capitalist abundance as a con, Adorno said that all the Yanks were being offered was ‘the freedom to choose what [is] always the same’. So samey that ‘personality scarcely signifies anything more than shining white teeth and freedom from body odour and emotions’. The hyperbole gives the game away. We’ve all laughed at somebody with over-bleached teeth or over-powering deodorant. But to conclude that such people have no personality or emotions is to ape the fascist mindset the Frankfurters thought they were subverting.

The Frankfurters could find fascism everywhere. Adorno, a gifted pianist and music critic, saw in his one-time hero Stravinsky’s abandonment of modernist experiment for neo-classicist tonalism what Jeffries calls ‘the arbitrary control of a Führer’. Later in life, says Jeffries, Adorno would claim that an orchestra conductor was ‘the musical equivalent of [an] authoritarian dictator’. As for American mass culture — movies, TV, jazz — that was pure aesthetic tyranny, a put-up job foisted on the masses to prevent them from listening to the late Beethoven that would foment revolution.

A feature writer on the Guardian, Jeffries does his best to make the Frankfurters’ thought reader-friendly. But there is no getting around the fact that none of them wrote clearly. Jean-Paul Sartre, himself no stranger to impenetrability, found Marcuse unreadable. And even Jeffries admits he has no idea what Adorno’s incantatory blither about ‘the non-identity of identity and non-identity’ means. ‘Work on good prose,’ wrote Benjamin, ‘has three steps. A musical stage when it is composed, an architectonic one when it is built, and a textile one when it is woven.’ Right enough, but there is nothing musical about Benjamin’s own prose, and the only thing woven about it is the wool it pulls over your eyes. Jeffries says the Frankfurters’ ideas remain relevant in what he calls the ‘different kind of darkness’ of our age. Anyone who believes that writing should illuminate the darkness will struggle to agree.

The post Frankly impenetrable appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in