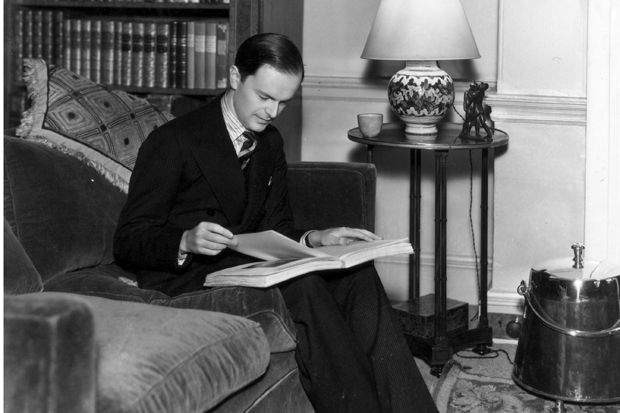

Steven Runciman, the historian of Byzantium, is a puzzling figure. He was an outrageous snob, once remarking that he would have enjoyed being the widower of a Spanish duchess, which would have made him a dowager duke in Castile. He particularly relished the company of queens (of the female variety), and he took the Queen Mother out to lunch once a year at the Athenaeum. But as Minoo Dinshaw shows in this richly original life, the snobbery was a subtle pose. Runciman was a tease who liked to play games with people, and he made a career out of being enigmatic.

His family were wealthy shipbuilders in Northumberland. His parents were both dedicated public servants — his father was a minister in the last Liberal governments. Young Steven threw off the fading, dull, Liberal world of his parents very early on. At prep school his best friend was Puffin Asquith, whom he addressed as ‘dovey, sweety, lovebird’. At Eton he was cleverer than his masters.

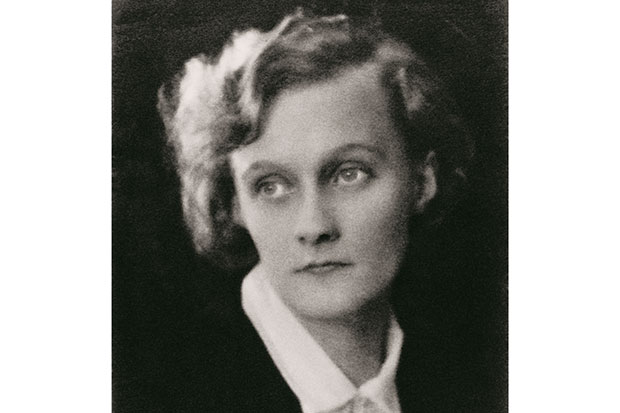

He won a scholarship to Trinity, Cambridge where he became obsessed with the pink-faced, pink-shirted Dadie Rylands, a callous narcissist. This was the closest he ever came to falling in love. Steven cut his auburn hair in a fringe, befriended Cecil Beaton and wore rouge; but he was a teetotaller with none of the self-destructiveness of the Bright Young People. His frantic attempts to wreck the marriage of his brother Leslie to Rosamond Lehmann —who not only was the most beautiful woman in Cambridge but mortified the exhibitionist Steven by writing an acclaimed bestseller, Dusty Answer — revealed him as thin-skinned, jealous and insecure.

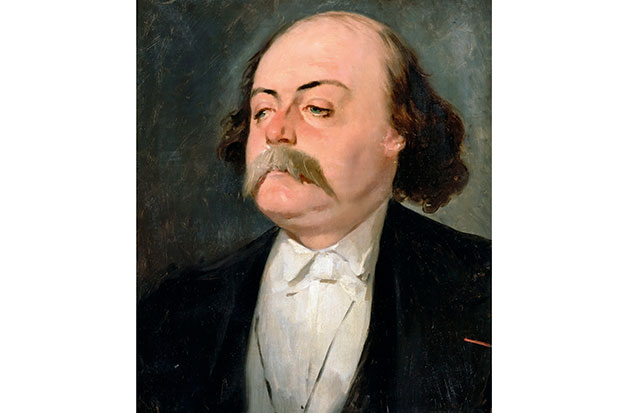

Runciman stayed on at Cambridge, where he became the only pupil of the dry-as-dust Byzantine historian J.B. Bury. He was a reluctant don, and he resigned his Trinity fellowship, aged 34, when he inherited enough money to live off his private income.

As Dinshaw relates, Runciman was far happier travelling, meeting the last emperor of China, with whom he claimed to play piano duets (a fib), or visiting Queen Marie of Romania in her bedroom. In Sofia, he encountered the grubby, footsore Paddy Leigh Fermor, who noted the ‘pleasantly feline’ Runciman’s exquisite white linen suit and spotlessly blanco-ed bi-coloured shoes. Needless to say, his History of the First Bulgarian Empire was dedicated to King Boris.

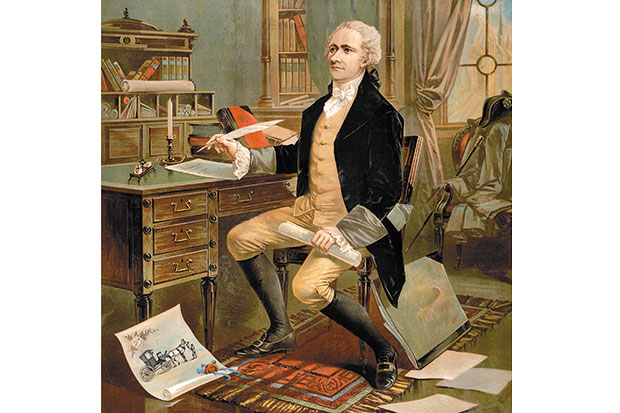

Guy Burgess was a pupil and friend, but Runciman had no sympathy with his Marxist politics. If anything, Steven was an appeaser, loyally sympathising with his father Walter Runciman, who was sent on a disastrous mission to Czechoslovakia in 1938 and wrote a report recommending the immediate transfer of the German Czechs to Germany. Steven nimbly sidestepped the hostilities in Europe and the suffering of his family (his heroic pilot sister, Margie, was killed when her Spitfire crashed) and spent the war in Sofia, Cairo, Jerusalem and Istanbul. It’s likely, as Dinshaw reveals, that he worked for British intelligence.

After the war, Runciman escaped the horrors of the Labour government by taking a job as head of the British Council in Athens (and of course befriending Prince Philip’s mother, Princess Andrew of Greece). Back in Britain, he retired to the Hebridean island of Eigg, which belonged to his brother, where he settled down to write his masterpiece — the three-volume History of the Crusades which he had been planning since 1938.

For Runciman, the

crusades were a disaster. Far from their being chivalric Christian knights, he saw the crusaders as thugs and barbarians, anticipating the Nazis. He had little time for the Muslims either. The sacking of Christian Constantinople in 1204 was ‘a crime against humanity’ because it destroyed the civilised, peaceful Byzantine world which, in Runciman’s mind, resembled Europe before 1939. Dinshaw is surely right to position the Crusades as a trilogy, like Waugh’s Sword of Honour or Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy, which was informed by the experiences of the war. But his analysis of the book as though it were a work of literature left me wanting to know more about the historiography: how far did Runciman change or challenge the conventional wisdom?

Dinshaw does a superb job in avoiding a chronological cradle-to-grave account of the life. Only towards the end of the book, for example, does he deal with Runciman’s homosexuality, and his judgment here is perfectly balanced. The account of Runciman’s old age (he died, aged 97, in 2000), playing the laird and host at his Borders tower Elshieshiels, couldn’t be bettered.

Dinshaw writes ornate sentences which occasionally require trimming (where was the editor, I wondered), and the book is overlong. But he vividly brings alive this secretive, ludic man, making good his case that Runciman, like all the best historians, should be considered, first and foremost,

as a writer.

The post In the company of queens appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in