At the end of Sunday night’s US presidential debate, the moderators snuck in a final question from a slightly shell shocked looking member of the audience. After an hour and a half of brutal, bitter exchanges, a man asked Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump if they could think of ‘one positive thing that you respect in one another’. In the resulting pause and exhalation it felt as though the country had seen itself in a mirror and realised it looked hideous.

Unlike some of our MEPs, the candidates for US president only sparred verbally in St Louis. And nobody watching politics from the continent of Europe (Beppe Grillo anyone?) should be too sanguine that it won’t happen here. Nevertheless there is something especially noxious happening on American prime time.

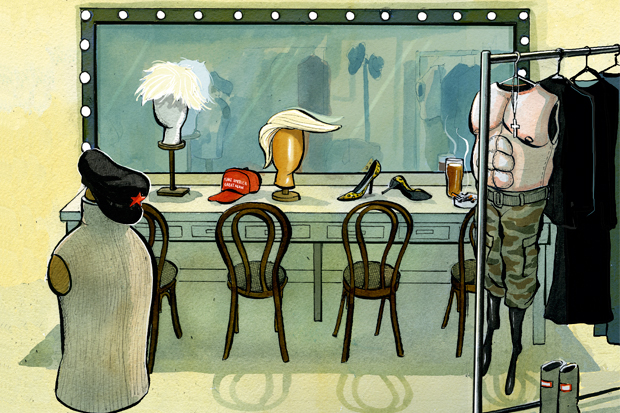

If there is a central cause, it is the triumph of entertainment over politics. Long an American temptation, this season it has finally won through. In part because every body had been enjoying themselves so much that they failed to notice that the nation was losing.

Consider the state of political discussion further down the food chain from the presidential debates. Most of it makes the Clinton Trump debates look like Lincoln Douglas. Take a recent public exchange between left wing blowhard Cenk Uygur and conservative pundit Dinesh d’Souza (both men with substantial media followings). D’Souza was promoting a new film arguing that Hillary Clinton should be in prison; and before a large audience, live streamed, Uygur gleefully pointed out that D’Souza himself had been to prison and then used D’Souza’s recent divorce papers to suggest he had also beaten his wife.

Such a level of debate has become wholly normal in America. At the end of the hour, the host remarked that a lot of young people were watching. What, in closing, would the two men say to encourage more young people to get involved in politics? Amazingly both men answered, rather than doing what any decent person would have done, which is to have hung their head in shame and left the stage.

Why would anyone behave like this? The reason, alas, is straightforward. This is how you get noticed in the great political entertainment business. Such people, like pundits and politicians up and down America, are auditioning for prime time. Though people often talk about political polarisation in America, they rarely mention the incentive for exacerbating it. In politics and in punditry, nuance and consensus don’t sell. Plumbing ever lower depths most certainly does.

Though the American media pretend to abhor the politics now on show, they are its progenitor. In a competition for viewers and readers, they have spent years turning political debate into ratings chasing bun fights. Fortunes have been made along the way. But they have turned America into a country where politics has become showbusiness for nasty people.

For the networks and media, the increasing polarisation and void are desirable: a necessary part of business. The worse the better. These bosses have encouraged the transformation of politics into WWF wrestling: a fake ‘sport’ in which participants and observers seem complicit — except some poor saps mistake it for real life.

It is wholly fitting that the noisiest contender for the presidency should have come from this world. For more than a decade, as star of The Apprentice, Trump was on prime time looking not just successful and tough but respected. When he began to run for the Republican nomination, it was as though The Apprentice got a bonus season. Each week during the primaries, Trump ‘fired’ one of his Republican rivals. The networks were thrilled by the record viewing figures and Trump regularly cited this as demonstration of his appeal. We’ll see if viewer satisfaction turns into voter satisfaction.

The public, for whom all this is being laid on, are understandably caught and conflicted. They both love it and hate it. Who could switch channels last Sunday night when among the guests Trump brought to the debate was Juanita Broaddrick and several other women involved with Bill Clinton in the 1990s? Who could not reach for the popcorn when Trump praised their courage in front of Hillary? The cameras even swung to catch Bill’s reaction shot, for goodness sake. But it seems unarguable that in the search for ratings American democracy is losing not just its sense of reality, but the most basic of decencies.

Of course, the American left blames the right for this replacement of politics with salacity. But the truth is that everybody has a part in it. Both sides endlessly portray their opponents not as people with whom they disagree but as comic book villains. If there is a reason why the left’s attacks on Trump haven’t worked so far, it is because they have dressed every previous Republican nominee in the exact same baddie outfit. Their last remaining option seems to be to see if the Putinista costume will fit him. He for his part seems not wholly averse to trying it on.

As the whole thing looks like consuming itself, it seems that absolutely anything is fair game in political entertainment. Last month Comedy Central broadcast a ‘roast’ of the actor Rob Lowe. Among those invited to take part was the right wing author and Trump supporter Ann Coulter. Before a glittering celebrity audience, broadcasting into millions of homes, one after another of the ‘roasters’ focused less on needling Lowe, more on viciously abusing Coulter. A procession of famous men queued up to call Coulter the ‘c’ word, vilify her looks and — in one case — advise her to kill herself. The liberal media were delighted and ran with it for days, before switching gear to profess outrage about the misogyny of an 11 year old recording of Donald Trump. But it is as though America as a whole has failed to find any mute switch, let alone the ‘off’ button.

Politics in Britain hasn’t become such an unreality TV show yet. But we have not avoided it entirely. Here too the divide between politics and showbusiness has occasionally grown alarmingly thin. Although Alan Sugar didn’t get near Downing Street, the UK Apprentice star was put into the House of Lords by Gordon Brown. And David Cameron promoted his co star Karren Brady in the same fashion. Like Sugar, her business skills were secondary to the ‘respect’ she accrued from reality TV.

For all its faults, the BBC helps to save us from a precise replay of America’s entertainment coup. Yet even here our resistance can be weak. It is clear that as a nation we increasingly favour the business of entertainment over the business of politics. Witness the replacement everywhere of news with ‘celebrity news’. What’s happened in Germany today? Who cares? Have you seen what’s happened to Kim Kardashian?

Responding to this trend, even respectable politicians are descending to the half way house that is the politics of character. Where once a premium used to be placed on the quality of an argument, today things are increasingly reduced solely to a question of who is saying it. There is no habit more clearly derived from the age we live in than the presumption that your back story, rather than your ideas, is of greatest importance. It too is a habit derived from showbiz, where infinite amounts of time are spent analysing accidents of birth and unimportant feelings, whereas in real life no one has time for such nonsense.

If we are to avoid America’s fate, it will be necessary to keep drawing a firm line between meaningful and confected debate. It will require politicians and institutions to earn trust rather than expect it. But it will also require the public to recognise the difference between being a viewer and being a voter. Because although it is true that the politicians don’t always know what is best for the public, it’s not obvious that the public do either.

The post Lights, camera, politics appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in