The subtitle for Mozart’s Così fan tutte may be ‘The School For Lovers’, but it’s as a school for directors that the opera is most instructive. From four lovers and two different romantic pairings, the composer spins a parable whose moral is as elusive as its morals. Faced with so much ambiguity (and so little political correctness) directors tend either to sand down the rough edges with laughs, or fling a capacious concept over the whole lot. It says something about the awkward profundity of this most inscrutable and affection-resistant of the Mozart-Da Ponte collaborations that it can take it. It says even more that you so rarely see an outstanding production.

While Christophe Honoré’s Così (seen this summer at both Aix and Edinburgh) ran headfirst at the opera’s misogyny, spicing its sexual manipulations with an unexpected racial dimension, Jan Philipp Gloger’s new production for the Royal Opera is interested much less in either sex or politics than in the seductions and illusions of opera itself.

His quartet of contemporary lovers make a late entrance to Act One, arriving through the auditorium clutching shiny red programmes and dressed for an evening in the stalls. It’s Don Alfonso (Johannes Martin Kränzle, all smiling menace) who beckons them on to the stage, welcoming them into a theatrical world in which he is ringmaster and magus, director and pander, conjuring sets and scenarios ranging from a Brief Encounter-style railway station and an art-deco bar to the Garden of Eden and an 18th-century theatre. Where does stage love end and real emotion begin? It’s a question worth asking, especially if your answer comes framed in Ben Baur’s stylish designs, but sadly Gloger’s answer falls short.

Together with dramaturg Katharina John, Gloger has evidently done a lot of thinking, and the resulting production is one long stream of directorial consciousness, proof that showing your working doesn’t get you extra marks in the theatre. But if emotion is to be so completely sacrificed for intellect, then you’d better get your conceptual ducks in a row at the end, something Gloger crucially fails to do. His lusty lovers have long since set aside their disguises (along with their clothes), rendering this final reveal something of an uncomfortable afterthought.

With its restless pacing, this production might do better under a different conductor. However rich the strings, however blowsy-beautiful the brass, there’s no getting away from the elderly tempi Semyon Bychkov gives his youthful cast. With four comparatively light voices (three house debuts among them) this was never going to be a momentous, weighty sort of Così, so why not make a virtue of light-footed brilliance instead? While both Alessio Arduini’s Guglielmo and Angela Brower’s Dorabella are excellent, and Corinne Winters makes an efficient, if vocally unremarkable, Fiordiligi, it’s tenor Daniel Behle (Ferrando) who finds the heart Gloger cannot, delivering an ‘Un’aura amorosa’ with such hushed tenderness, in so brave a pianissimo, that it makes all the cynicism around it seem cheap and insubstantial. It may not offer them up easily, but Mozart’s score holds the answers to even the libretto’s ugliest questions,

if only we take the time to listen.

From Royal Opera present to a glimpse of its future, courtesy of Welsh National Opera’s Macbeth. The production is directed by Oliver Mears, last week named as Kasper Holten’s successor, taking up the post of director of opera next spring. This young director, whose biggest job to date has been at Northern Ireland Opera, is an unexpected choice, and an exciting one, whatever this dud of a show might suggest.

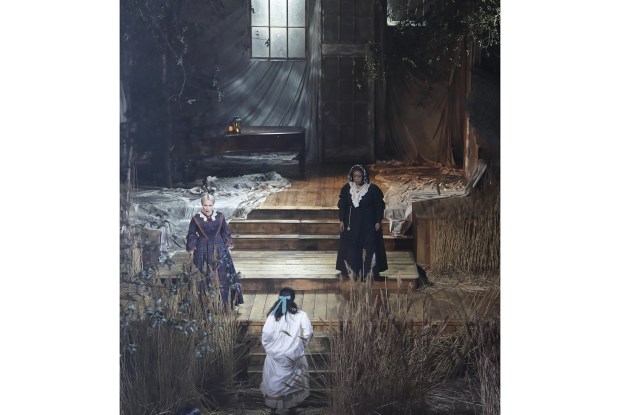

Mears’s Macbeth takes Shakespeare’s Scottish Play and distils its tragedy through the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s. Set in a disused hospital (or possibly a public lavatory, it’s hard to tell), it insists on the factional horrors, the cruelties of Verdi’s opera, without offering anything to temper them. Power’s seductive, magical lure is lost among a chorus of crazed witches, whose ritualised movements are empty symbols and an Imelda Marcos of a Lady Macbeth, more interested in her collection of furs than in her husband. The ever-present drop-curtain dilutes the tension each time it falls, holding back a drama whose knife should twist evenly and constantly from its first wounding.

The production is saved by some fine singing, principally from Luis Cansino in the title role, whose thick-set baritone is an honest squaddie of an instrument, easily led astray by the charismatic power of Mary Elizabeth Williams’s authoritative (though occasionally pitch-wayward) soprano. Miklos Sebestyen makes an appealing Banquo and Miriam Murphy impresses in the tiny role of Lady-in-waiting. Despite occasional lapses of unity with the chorus, Andriy Yurkevych’s orchestra fill in all the colours Mears’s production drains from Verdi’s opera. Let’s hope this is a lapse from an operatic risk-taker, not a portent of things to come from a director who shall be king hereafter.

The post Losing heart appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in